Did you know that John Lennon’s first guitar was a Gallotone Champion acoustic that he ordered from a catalog, or that George Harrison played a Framus Hootenanny 12-string on “Help," or that Ringo started playing a Ludwig Downbeat drum kit in 1963? You would if you read Andy Babiuk’s book, “Beatles Gear, The Ultimate Edition,” which chronicles the band’s history through the lens of the instruments and gear they used onstage and in the studio. Babiuk sat down with Audiofanzine recently to talk about the book, the Fab Four and their gear.

Babiuk’s book, published by Backbeat Books, is a coffee-table style tome full of information, anecdotes, and tons of photos. This is the second edition of the book, significantly expanded from the original, which was published in Britain in 2001.

“I worked directly with Olivia Harrison and with Ringo, ” says Babiuk about his research for the new edition, "and McCartney’s been really cool, and Yoko was great.” His other sources included the late George Martin, Geoff Emerick the late Neil Aspinall, and many others.

Babiuk owns a boutique guitar store called Fab Gear in Rochester, NY, and has played for a long time in The Chesterfield Kings, which he says was largely inspired by bands of the British Invasion era.

I really liked the way that the book weaves in the band’s history along with the gear info.

Thank you. I wanted it to be a story about the Beatles from their perspective as musicians. You’ve got to tell the story of the band, you can’t just make it a list of things. And also, I was very happy that we were able to put the album covers in. Because it’s another way to give perspective of what was happening and what was being used during different phases of the band. We all remember those records and the covers, and that helps tell the timeline of where you’re at.

Some of the band’s early instrument choices were influenced by how difficult it was to get American brands in England, right? For instance, Paul’s choice of the Hofner bass.

Well the Hofner was more because they were in Germany. You’ve got to remember the mentality and the age of these guys when this was happening. McCartney was a teenager. He was either going to be out of high school and into some sort of art college or something, or he was going to go with his buddies and drink beer and pick up chicks and play music all day in Germany for months at a time. “Screw it, man, let’s go have a party!” That was the mentality. But along with that, they didn’t have any money. They were all living in a room together with a candle. It was wacky. Hofner was a German company. They were in the center of Hamburg. There were a lot of music stores there. So the Beatles were actually able to access and look at instruments that were available. The “violin” bass was unique because it was symmetrical. And McCartney said this himself. Most basses, like Fenders and others, are asymmetrical.

Oh right, because he needed to flip it over to play it lefty.

He saw it and said, “Gee, you could flip this over it would be the same.” I’ll guarantee you this, and everybody from that time period told me this, you could never, ever walk into a music store and see a left-handed instrument. It was just never going to happen. So McCartney was thinking, “Hmm, I’m in Germany, this is a German company. Can they build one and put the electronics on the other side?” The guy said “sure.” He was just trying to make a sale. He called up Hofner, “Hey, we’ve got a sale for a lefty, can you build one” “Sure.” And there you go, it’s as simple as that. And plus, it wasn’t expensive. It was a German-made bass, and they weren’t really sought after. Nobody played them.

And yet Paul ended up sticking with the Hofner for the most part, right?

Yeah, he did. And I think a lot of it has to do with that it was lightweight. He told me that. It doesn’t weigh anything. You can have it on your shoulder for two or three hours and it’s not pulling on you, it doesn’t weigh anything. And the other thing, too, if you’re a guitarist you’ll relate to this, when you have an instrument that you’re really familiar with, you tend to like to play it, because you know everything about it. You don’t have to look at the neck and you know exactly where the fifth fret is. You can just feel it.

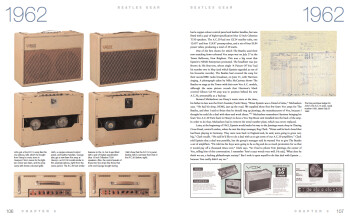

How about their use of Vox amps? Were those pretty much the main guitar amps they used when playing live?

Vox was a British company out of Kent, England, which is a suburb, basically of London. Remember that in the late '50s, you couldn’t buy American-made Fender amps. They would have preferred to, but you couldn’t get them. So there were companies like Vox that were taking advantage. And that’s what the [British] government set up the trade embargo for, to build British industry. And the Vox amps are a good case in point. If Fender amps were available, Vox might not have existed because they wouldn’t have had as many sales — everybody would have wanted the cool Fender stuff.

So Vox amps were the best ones the Beatles had access to?

The Beatles knew that that Vox amps were the best you could buy in England then, but in 1963 they didn’t have any money. When they did their first audition, Brian Epstein was pulled aside and told, “Look, these guys have some potential, but if you’re going to make them into a real band, you have to shape it up a little bit like, go get them some real equipment.” Their stuff was all falling apart, was buzzing. You’ve got to remember, they’re using this stuff every day. It’s getting slapped around, beat up. You know how amps get. Tubes get funky, [they start] oscillating and stuff.

So what happened?

Brian Epstein was told, “You know, if you’re going to be serious about this, get these guys some real equipment.” Brian Epstein didn’t have any money, his parents did. So he went and signed for these two Gibsons [J-160E models for Paul and John], he took Ringo to get a drum set. And then, he knew they needed new amps. And so, with balls of iron, he goes marching into the store. Jennings was the company that owned Vox, and they had a store on Charing Cross Road in London. Epstein goes marching in there and talks to the clerk, Reg Clark, I interviewed Clark about it. He says this guy comes in and says “I manage a band called the Beatles and I’m asking for a set of amplifiers for them.” Reg was like “OK, sure, we’ve got AC30s, we’ve got a bass amp.” But Epstein said, “But we need them for free.” He said, “I can’t do that. I’m not the owner, but we don’t give away amps.” Epstein said, “The Beatles are going to be the biggest thing in the world, and if you give me free amps, I’ll make sure that they never use anything but Vox amps, as long as I’m their manager.”

Wow, that’s nervy.

So Clark was a little bit charmed by how arrogant and kind of crazy Epstein was, so he calls up Tom Jennings, who was in his office around the corner. And he says, “Tom, I’ve got this guy who says his band the Beatles are going to be big, and he wants some free amps.” Tom Jennings’ response was “What the fuck does he think we are, a fucking philanthropic society? I’m in a business to sell amps.” The story goes on that Clark, for some reason, was eventually convinced by Epstein. “OK, fine, we’ll give you a pair of amps. But you’ve got to always use Vox.” And sure enough, he gave them two AC-30s, not even a bass amp, because they didn’t really have a bass amp yet, but two blond AC30s. And sure enough, the Beatles popped. And as they popped, Vox was going “Holy shit, these guys are using our amps!” And so, whatever the Beatles wanted from that point on, they gave to them.

Let’s talk a little about the Beatles’ stage gear. You see films of them playing at all of these shows with everyone screaming. Did they have any kind of monitors? How did they hear themselves sing?

There were never monitors. You sang, and whatever you heard bouncing off the P.A. or the walls or whatever — that was what you heard. They were just good at it. They did so many shows together, and they were used to harmonizing and doing what they do really well.

So monitors didn’t exist then?

There was no such thing. It’s funny, because in the Rolling Stones book [Rolling Stones Gear], I point out that it was the Stones who really invented the monitor. They were the first band to take a P.A. system on the road and actually experiment with monitors. It was in the '69 tour. They weren’t using what we consider wedges, they’d use regular boxes, and they were pointing at their ankles. You’d see it, like when they were playing at Altamont, they had speaker cabinets pointing at their ankles. They actually used to take speaker cabinets and put them where the amps were, and face them toward the stage. They didn’t realize it would make the microphones feedback. They were the first band that did it. But that wasn’t until '69, so prior to that nobody was doing it. The only time the Beatles did it [used monitors] was when they did the rooftop.

I wonder what it was like from the audience perspective at a Beatles show.

I never actually saw the Beatles play live, but I run into tons of people who tell me they did. I say, “Great, you saw them live. I know it was exciting and everything, but did you actually hear them?” And fifty percent of the people say they heard nothing, just the screaming. And the other fifty percesnt say, “Yeah, you could hear them. You heard screaming, but you could hear the band play. You didn’t hear them very well, but you could hear them play.” So I think it was perception.

You had something in the book from the front-of-house guy for the Shea Stadium show, talking about the PA, and it was tiny for such a large venue — only a few channels.

It was primitive at best. Back then, public address systems weren’t used for music. When the Beatles played Shea Stadium, there had never been a concert that big, ever. So why would you need something really loud and big, and miking everything? Who would even think of that? The biggest thing that they would do was a football game or a baseball game. The only thing you needed was to have an announcer talking over it. So that’s why when they played at a hockey rink or a football stadium or a baseball stadium, they were literally singing through an announcer’s PA system that was used for the games.

Yikes!

It was because there was no [live] sound. No one had done it before they set the precedent for it. And it’s interesting because the Rolling Stones did the exact same thing. But they continued playing beyond '66, '67, and as technology moved on, they were able to incorporate the new stuff into their live sets. The Stones really took it to the next level.

Let’s talk about EMI Studios [later renamed Abbey Road Studios], where Beatles recorded.

I interviewed all the engineers that worked at EMI at the time. It was kind of a weird place. First of all, they didn’t look at the recording studio the way we look at it now, as a creative place. It was more like a laboratory.

I heard that the engineers had to wear white lab coats.

Yeah, really clinical. And it was very strict. They looked at it very scientifically.

One thing I was surprised to read was that during the sessions for Sgt Pepper, Paul recorded his bass using a DI box, which had just been invented by the engineers at EMI. The DI seems like such an obvious thing, it’s surprising that it took until 1967 to invent it.

I think it was Ken Townsend that designed it. It’s in the book. They wanted to come up what they called “direct injection.” Where you would change the impedance, because you can’t plug a bass guitar directly into a board because there’s an impedance difference. It’s pretty simple if you think about it.

Exactly my point.

The reason why was that at EMI this stuff was all very clinical, and you weren’t allowed to mess with it. There’s a great classic story. The engineer who worked on that session told it to me. This was during the recording for The White Album. At this point the Beatles sold millions and millions of records world wide. They’re probably floating the boat for everybody’s paycheck in the whole company of EMI. They were allotted time because of Sgt Pepper to experiment, and to be musical in the studio. But they weren’t allowed to “abuse” the equipment. This is what the engineers told me. If you did something with the equipment, using it in a way that was not approved by EMI, it would be considered abusing the equipment, and you would get written up and potentially fired for it.

Even at that point, when the Beatles were that big?

It gets better, check it out. So the Beatles come back from India. They write all these basic acoustic songs over there, and they bring them back and start recording them. Like “Blackbird, ” “Dear Prudence.” A lot of very cool but mellow stuff. In '68, you look around London, what’s going on: You have Jimi Hendrix, you have Cream, you’ve got a lot of very heavy music being played. The Who was playing some pretty heavy stuff. The Beatles recorded “Revolution #1”, which is kind of a laid back, cool, blues type of song, almost. And Lennon realized what was going on in London at the time. “Fuck, we’ve got to do something really heavy.” So the engineer who worked on the session told me Lennon was upset. He came in one day and said, “We’re going to do Revolution, ” but we’re going to do like a revved up rocker out of it, and I want a really distorted guitar."

How did they achieve it?

First, they brought in all these fuzz pedals, like the Tone Bender and the different fuzzes that were available at the time, and Lennon was trying them, and he said, “That’s not distorted enough. I want it really, really distorted.” So one of the engineers was telling me that he told John, “Look, John. What you’re talking about is that you want the whole frequency range of the guitar to be distorted. Fuzz pedals are more midrange, and that’s why you’re not hearing the sound the way you want. If I was to plug the guitar directly into the board through one of these DI boxes, I can overdrive the preamp, and put it on full, and it will be the widest frequency of distortion you’ve ever heard. But the problem is, I’ll get fired. I’ll get into a lot of trouble for this. We can’t do it.” And Lennon being the smart ass said, “Fuck it.” So here’s what they devised: In EMI Studio 2 there were these big metal doors. You know how in schools and stuff, they have those push handles for the swing-out doors? They took one of the interns, and they told him, “Put this chair, put the chair legs into the two handles, put them up onto the door itself. So you couldn’t open the doors from the outside. Basically, a chair was holding them in place, so you couldn’t open the handle. Lennon goes up into the recording room, and they had to do this thing, overdriving the board, at the beginning of ”Revolution, " that really heavy guitar, while some kid is watching the door so they don’t get in trouble.

[Laughs] That’s crazy!

This is the Beatles, during The White Album. The Beatles had to be afraid of some guy getting fired? They could have said, “Fuck you, we’re buying the fucking thing.”

You wonder what would have happened if they’d been able to record somewhere where they really had a free hand.

Yeah. And Lennon was really into experimenting. With the DI box, he was telling Ken Townsend, he said, “OK, when I do the vocal, can you plug that DI box into my throat?” He didn’t understand how it worked. He had another thing where he wanted to sing through a microphone through water. I was told by a lot of the engineers that he didn’t like the sound of his own voice. He really hated it, and he wanted them to always change it and make it sound different. A lot of singers are like that, they don’t like the tone of their own voice.

Would you say that Revolver was the turning point from when the Beatles and George Martin started trying to push the envelope in terms of recording techniques, at least as much as they could at EMI?

Yeah, it was really a point where, for instance, they started using headphones. You’ve got to remember, prior to that, when they did vocals, there was a speaker on the wall that they’d play the music through and they’d sing.

There must have been a lot of bleed.

Yeah. And if you listen to the raw tracks of the vocals, you’d hear the music in the background. That’s just how they did it. They didn’t have headphones. It was evolving. I mean it was evolving as they were doing it. But as a band, obviously, they had hits, but I think what was happening was there was still a lot of restrictions — the points we’ve brought out. But at that point they were buying different kinds of guitars. “We can’t use the same Rickenbackers, we can’t use the same amps.” They started using Fender amps, big Showmans. They knew that it sounded different. They that a Gibson 345 sounds different than a Gretsch Country Gentleman, or that an SG sounds different than a little Rickenbacker. They knew that an Epiphone Casino sounds different.

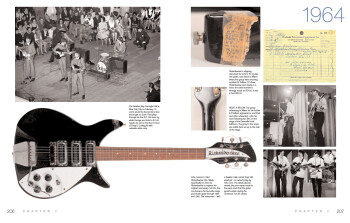

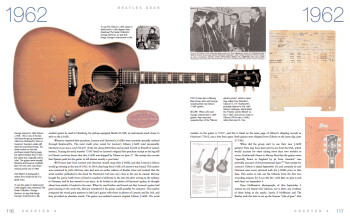

Speaking of guitars, let’s wrap up with the story from the book about how back in 1962, John and George ended up with Gibson J-160e guitars, .

They went in to order a pair of electric jumbos, and they thought they were ordering a pair of ES-175s like Tony Sheridan had. Tony Sheridan told me this —Tony’s passed away since. He used to play with them in Germany, and he was the headliner, because he was a star in England so he actually had hit records. And he went to Germany to play, and the Beatles used to be his backing band. They used to open for him. He had loot, so he was able to buy real guitars. He had a really cool electric Martin acoustic, but he also had a Gibson ES-175, which is a big jazz guitar with f-holes on it. Tony told me that Lennon and George would always say, “Hey, Tony, can I borrow your Gibson jumbo.” And he said, “Yeah sure.” And they referred to it as an electric jumbo.They didn’t know it was an ES-175. So when it came to the time when Brian Epstein said, “We’ve got to get you guys some new guitars, ” the trade embargo in England had been taken down about a year or two before, so the franchises for American instruments in England were brand new. Most places couldnt afford to actually stock the stuff, but they had a catalog.

So what happened?

So these two kids go in to Rushworths — a store in Liverpool that was a Gibson dealer — with their manager. At that time nobody knew who the hell a Beatle was, they hadn’t even recorded a record yet. So they go in there and they say, “We want to order a pair of Gibsons like our friend Tony Sheridan has.” “OK, so which model?” “I don’t know, it’s an electric jumbo.” So the guy at the desk literally wrote down, “Gibson electric jumbo”, and he took the order down and said, “We’ll call you when it gets here.” So he goes to the 1962 Gibson catalog, because it was early 1962, and he looks up “electric jumbo.” And if you look in the catalog, it lists the Gibson J-160e. “J” for jumbo and then “160” was the model and “e” was the electric. So the guy ordered them. The guitars show up from Kalamazoo and the two guys are really happy, “Oh man, we’re going to get our guitars.” They go in there and Tony Sheridan told me that they were both kind of set back. They said, “Shit, these aren’t the guitars we wanted. But we shouldn’t say anything, because we might not get the right ones, so we’ll just keep these.” And subsequently, the next day, they went out and recorded “Love Me Do.” And the Gibson J-160e became a signature tone. But technically a real crappy guitar. It sounds horrible.

The J-160e is an acoustic with a magnetic pickup stuck in it, right?

Yeah, and it has a plywood top. So it doesn’t sound like a Gibson Hummingbird or a Dove or a J-200. It’s really a nasaly, midrange sound. It was a matter of happenstance that they ended up using it.