Jack Douglas’s list of credits reads like a who’s who in the Rock ‘n’ Roll Hall of Fame, and includes John Lennon, Aerosmith, Patti Smith, Alice Cooper, Cheap Trick, and many, many more. Not only is he a legendary producer, but also a talented bassist and composer. Audiofanzine had the chance to meet this legend while he was in Paris producing the French band Blackrain.

Hi Jack, it’s a great opportunity to have you in Paris! Can you tell us what you are doing in France right now? What are you working on?

Uh oh. What am I doing here? [Laughs] I ran into my friend Danny Terbeche at the Cannes film festival, and he said, “I have a great band, a French rock band.” And I said, “No, there’s no such thing as a French rock band!”[Laughs] You know there are French bands, yes, and they make French music mostly, it’s all good. But when you think “rock, ” you know, you don’t think French!! Not to compete outside of France. But he said, ”No, listen" and he sent me a demo. And it was very good, I mean really, really good. I met the lead singer and he lives what he’s singing — this is his life. And so I said “Ok, I’ll do it, and I’ll come to Paris for the summer and you do all the leg work: you book the studio, you do everything!”

So here I am and it’s been great; the studio turned out to be really good, very familiar because it was a kind of mid-70's, Westlake-built studio. So it looked like I was in New York in 1975, or in LA, in one of the Record Plant or Westlake studios! The design was very similar: same monitors, same bass traps. So it felt very familiar. The room was a bit small but I wasn’t recording the band live; it was drums, and bass, then overdubs. So yeah, I haven’t really seen a lot of Paris because I’m staying up here in the north side of the city, but I had a couple of days off and I did all; I went to the museums. I had a great time in Paris, and I return to New York tomorrow. I’ve been here almost 2 months!!

I’d like to go back to the beginning of your career. You were born in New York City; you started your career as a musician — that’s what I read — you even moved to England to play in some bands. Can you tell us a little bit more about the beginning of your career, including songwriting for Robert Kennedy’s 1964 senatorial campaign?

Yes actually I started writing campaign songs for Robert Kennedy. I was only 15 and, you know, it’s because I played folk music. In 1964, it’s what they wanted, folk music was very popular. You could go up with a guitar and warm up people at a political rally and sing all these songs against this guy and for this guy and then the big songs and then they would introduce Robert Kennedy to make a speech. They wanted young people to participate, but they didn’t know I was only 15. When I finished that I went back to school to finish my last year in high school. And then the Beatles became popular, I changed from folk music, I traded my old Gibson, a nice acoustic guitar. And with the little money I got a 1954 Black Les Paul Custom. I think it cost $175. Now it would be worth $175,000, if I had it, you know! [Laughs] I traded that later for a bass but it was a beautiful guitar!

And after that, the band I had got a deal. We had a hit, and then after school, between trying to get a degree, I was playing in bands. I played with the Angels, you know [singing],"My boyfriend’s back…” I was bass player for Chuck Berry’s band, and I just stayed on the road, playing with different bands for many years — and with different people.

In 1965, I went to England with one member of a band; we went on a tramp steamer. It was the cheapest way to Liverpool but it was very uncomfortable! We crossed the North Atlantic in the middle of the winter and it was terrible, just terrible! I can’t describe how bad it was but it was bad! When we got to England, we were denied [entry]. We had our guitars but we didn’t have work permits and we were coming to work. So I ended up escaping, I escaped from the ship! And I bought the album Rubber Soul the day it came out, in Liverpool. It was very exciting.

I saw a newspaper office and I went to the newspaper office and told them my story and they said: “That’s a good story! We like it! Go back to the ship and tomorrow we’ll have all this press. We’ll come and take pictures and do this whole thing while your boat is still in port, for five days!” My friend didn’t expect to see me again, you know, because I escaped from the ship. He was surprised to see me, and I had this album, and I told him: “We’re going to get saved.” And so the next day, the newspapers came and we were on all the front pages. They hired TV there, and they had girls marching up and down in front of the ship — all fake, you know — “Free the Yanks!” And the day before the boat was going to leave, the immigration people came and they said: ”You guys make a lot of trouble for us you know? So we’re going to let you come in for 60 days on a visa, but no guitars and no amps!" So we said, “OK, ” and we shipped them back.

The newspaper guy put us right into a band and he was going to write a story. After a month or so playing, some guy came over in a cafe and asked for our autograph, and an autograph for a guy in the back, a friend that was in the car. We walked outside and it was immigration police and they stopped us, strapped us, put us in chains on the train, sent us to London, then to Southampton, and deported us. But it made a lot of press before I left! [Laughs] It was a great adventure for real young men. I wanted to get a little bit of what was going on in Liverpool. It was important to me, musically. Because what I was playing, I wanted to understand it so. I went to the Cavern, you know, I saw bands playing at the Cavern.

Is it true you worked at the Record Plant as a janitor?

That’s how I got in, and it was 1969, that summer. I was a terrible janitor, so they finally got like a real union janitor — but for the beginning I was OK — so they made me a general worker. And so, we were recording the Woodstock festival, in upstate New York. They had a truck up there, the Record Plant did, and they were recording Woodstock. They were taking the tapes out by helicopter and then they would bring them to a place where a van would pull up and they would load all the tapes in. Then all the artists would come to the Record Plant to do their overdubs, to fix it right away, any mistakes. So the van would pull up in front of the studio, I would run out with a hand truck, load up all the tapes and then run inside and…I didn’t even know what artist, it just said what studio it’s going to A, B or C. But I ran into studio A, I was running in with a load of tapes [smelling] "Wow, some strong pot!” [Laughs] and I could hear a “zzzziiiii”. Oh I know that sound, it’s like a Marshall stack, just buzzing away!

You had to walk through the studio to get to the control room. So I open the door and I walk in with the tapes and there’s smoke, and out of the smoke comes Jimi Hendrix! And he’s got a joint in his hand, you know. And Jimi Hendrix offers me a joint! He’s like: “Hey, would you like to…?” I’m like “Wow I’m definitely in the right place!!!” So I just knew this was where things came out. And this is where I met Eddie Kramer; we’ve been friends for million years. I knew I was in the right place. That’s where I wanted to be. I practically lived there, you know, I worked so hard. And because I was so obsessed with the [tape] editing, I became really good. When I finally got to the tape library, there was the tape librarian, I was like an assistant engineer AND tape editor. My specialty was that I could cut the tape really well…I became a good editor was one of the reasons why I ended up on the Imagine album.

Talk about Imagine

When it came time to do the Imagine album. They said: “There’s going to be a lot of editing involved.” They said: “Oh, get Jack, you know, we’ll put him in a room and he does the editing.” Because what happened was John recorded a lot of material on a 2-track, not stereo, but like track 1, vocal, track 2 piano, track 1 vocal, track 2 guitar. And he wanted to take those songs and overdub on them. But he needed to transfer to multitrack, which was 16 (ips) at the time. But he wanted to edit the songs. So first you had to transfer to the 2", then cut the 2" and there were handwritten notes in the boxes of the 1/4". John said: “After chorus 1, on one beat after this word, cut the chorus 3, same place.” But you would do this after the transfer. So I transferred through Dolby onto the multitrack.

And for a week, sessions were going on, he booked all the rooms. He had sessions going on in two other rooms and I was out of it, somewhere else in the building, on the same floor. I’m in a room, hearing the songs long before anybody else, hearing this and I’m making the transfers, not seeing anybody. But that’s good; I’m on the project! On the weekend, the door opens up and John Lennon walks into the room — to my room! [Surprised] And, you know, I’m a big fan, it’s like crazy! He says to me, “Do you mind if I’m sitting here for a few minutes, I need some place to get away from everything?” So I said, “No, eh, sure, have a seat! I’m the guy that’s doing all the editing!” He goes “Yeah yeah, you’re doing a good job, thank you, thank you!”

And he sits down, there’s a couch on the other side of the console and I’m working here. All I can see is his feet up, his two sneakers up on the window ledge and cigarette smoke. I’m continuing working and he just sits in there, having a smoke. Finally, after 10 or 15 minutes, I said to him: “Hum hum, I’ve been to Liverpool!” His head pops up. He says:" You’ve been to Liverpool? Where are you from?" I said:" I’m from NY, born and raised, but I went to Liverpool because I wanted to get involved with the music." He says: “Really? 'Cause everybody there wants to come here! I can’t believe that you went there, it’s very funny! How did it work out? Did you get involved in the music?”

“Oh, it worked out both good and bad, ” I said. “I really had a great time but I ended up getting deported but it made a lot of noise before I got deported.” And he looked at me and he said, “You were one of those crazy Yanks who was all in the newspapers, were you?” I said “Yeah!” And in one of the pictures — on the front page of the Liverpool newspaper — was me playing my '54 Les Paul, on the boat, and I got a Les Paul in my hand. He looks at me and he goes:" '54' Les Paul Custom, right?" And I said “Yeah!” And he goes “I can’t believe I’m meeting you! This is incredible!” [Laughs] “We used to look at all those pictures and your adventures and thought 'Wow, this is really cool!' We’d laugh you know, 'What assholes they were coming over here?'”… But he said, "I can’t believe I’m meeting you!”

That’s a beautiful story!

Yeah! yeah, all because I went to Liverpool! [Laughs] There’s this picture online of the newspapers and everything. That picture of me with the guitar, you can find it online.

Ok. So that’s how you started with John Lennon… The other “big name” that we cannot forget to mention is Aerosmith. How did you get to work with them?

Well, with Aerosmith, I was engineering the first New York Dolls album and Todd Rundgren was the producer. And that was not a really good combination. I was a downtown guy, I hung out at Max’s Kansas City [a night club in Greenwich Village], I knew everybody, Patti Smith and the Dolls, Lou Reed, all. They were part of where I lived in New York. So I knew everybody there. And so when they decided to do the album, the label said, “Oh we want Todd Rundgren, he’s a really hot producer!” and the Dolls said “Yeah, but can we at least get Jack to engineer it? Somebody we can talk to that knows us?” So I went on to engineer that album and pretty soon Todd didn’t want it, he was uncomfortable with the band so he didn’t show up, sometimes he just called and “How was it going?” Those guys were pretty fucked up and hardcore you know, you can imagine! And so somehow we managed to do that record and no one thought it could be done. 'Cause they were undisciplined, they weren’t professional musicians, they were fucked up most of the time, on dope…it was a mess.

But we managed to make what turned to be a classic album. And Todd came in and we mixed it but he wasn’t there for many of the sessions. So the managers of the New York Dolls were very happy with me and I never said anything to the label; I kept my mouth shut about what went on there. The label would call, [I’d say] “Hey Todd’s in there, he just went for something to eat, don’t worry about it, it’s all going great!” But the management was like “Phew. Wow. We didn’t think you could get it done! We’re very happy with you. Maybe you’d like to take a look at our baby band?” which was Aerosmith. “We don’t know if they’re going any good or not!”… I said “Sure, send me off to Boston hear them!”

Because of my love for the Yardbirds, after the show, we sat down, we started to talk about [Jimmy] Page and Eric [Clapton] and the guitar sound, the influence of the band. It turned out that we had so much in common, the band and myself, that we just hit it off. And so we started a very long relationship. We became friends again, we went to hang out together a lot…Sometimes it can produce some pretty bad trouble but… [Laughs] Not for a few years! For a while it was all good! [Laughs]

I’d like to go back a little bit on the technical side, just to talk a little bit about the equipment you use, and the things that you love. Do you have your studio now? Do you have your own setup somewhere?

Yeah, it’s in Los Angeles, at Swing House. It’s an old API board but mostly it’s just filled with outboard equipment. One room we have a Neve 8058 and the other is an API. We can mix in one room and track in another. But you know, I use a lot of outboard, mic pre’s; I mean with the old Neve, there’re great mic pre’s. But you know sometimes they’re a little dirty, there are some things they don’t like, some instruments, and then I prefer to use outboard. There are some stuff that I like in the box, like all the Waves plug-ins and I love Decapitator from SoundToys! I mean there is some really cool stuff in there but I prefer to break out a mix on a board and then use as much as stuff that I like. You know I like to listen to what instrument I’m recording and decide what mic pre I want to use, because there’re so many great mic pre’s now, there’re so many beautiful, musical mic pre’s.

|

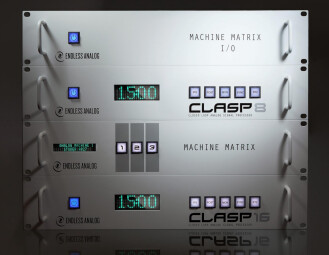

In addition to recording directly to tape, Douglas uses an Endless Analog CLASP system to get the sound of analog tape into his productions.

|

So which one are you using? I’ve heard that — in the new stuff — you like the Grace Design for example…

Oh yeah! But you know I ended up with the 1073!! [Laughs] A 1073, two compressors, an 1176 an LA2A and a Neumann 48, which is a 47 with a figure-of-8 [pattern]. For vocals.

So it’s basically vintage stuff?

Yeah, yeah. I still like that sound a lot. It’s just the harmonics…It seems to almost work for everyone, you know. Except for John. On John I used a 67. It’s funny because when you look at all the classic pictures of John and Paul singing, there was a 47 or 48. When you see them both singing side by side, it’s a 48. But I had a 67 when I recorded him at Hit Factory; when I put different mics for him to try, it just sounded perfect on him. He sounded like, very close. He liked the sound of it in his headphones. And I like it a lot. So, some 67s are great.

Do you still print to tape? Do you still use tape?

I use tape and [Endless Analog] CLASP. But you know this is depending on what kind of music I’m recording. If it’s rock, I’m going to tape. I have three CLASP systems. When we did the Aerosmith album, we’re going to one A800 at 16 tracks, running at 15 ips, that was only drums. Then there was a 24 tracks running at 30 ips and that was everything else — except for the bass — that was a running on a mono machine at 7.5 ips…And I mix to tape, I mix to 1/2" on an ATR but I also mix to Pro Tools and when I get to the mastering — 'cause I go to them, I go to every mastering sessions — I put them both up and he puts it in Sonic or whatever program he’s using and then I listen and I pick; that matters to me.

I used to use one more deck, I had an old 300 tube 1/4" that I really hot rod at the electronics so it’s very hot. There aren’t even meters on it anymore! I took the meters out! Just didn’t matter! And I would just cram the levels up to this thing and then I would bring a 1/4" tape in and — I don’t use it anymore because it’s become too hard to maintain — but it wasn’t uncommon for me to go: “Ok, we’re going to use all the choruses that going to come from that 1/4” machine. I don’t care. The intro can be from Pro Tools, the verses can be from the 1/2" machine but the choruses are going to come from that, because it’s just got crunching stuff…" But now there are plug-ins for tape simulation that sound very close to that sound so… It’s not worth for me to try to maintain this machine anymore.

Which ones do you like using? The Waves Kramer Master Tape, the UAD Studer A800?

On the converter I have, there’s a tape simulation knob. That sounds great too! That’s the Lavry Blue! Sometimes I put that on: “Ooooh it sounds pretty cool!”

Great! Let’s talk about your point of view about the music industry today. How do you see the different things today, business-wise and technical-wise? What’s missing for you today?

Ok! I don’t think anything’s missing…I mean, it’s really exciting, 'cause there are so many kinds of music that people can listen to now but they couldn’t listen to before. You would be hard-pressed to go to a record store and find…you’d have to go the specialty stores and now you can find almost anything you want online. I mean the sad part is that, for the most part, you’re not paying the artist for this…people are putting it up so you can just tear it and download and it’s free. That’s the sad part: it’s hard for an artist to make a living off recorded music. You know, recorded music has just become a way to sell tickets to a show or a club but recording music right now is more exciting than it has ever been. There are more different kinds of music that has ever been before, so I’m excited about it.

I’m also excited about the fact that amateurs can make really cool music at home. I’m not competing with them, I’m competing with me; I’m always excited to hear what somebody’s doing. I like it when we put our stuff, like a new mix, we like when people mix our stuff. Or you know when I got some DJ to remix something, it comes out really cool. A lot people resent the fact that there are amateurs recording their stuff at home but you know at one time I was an amateur. I had a little Crown machine and I used to like to record my band and I thought it was the best thing ever! I think it’s really cool.