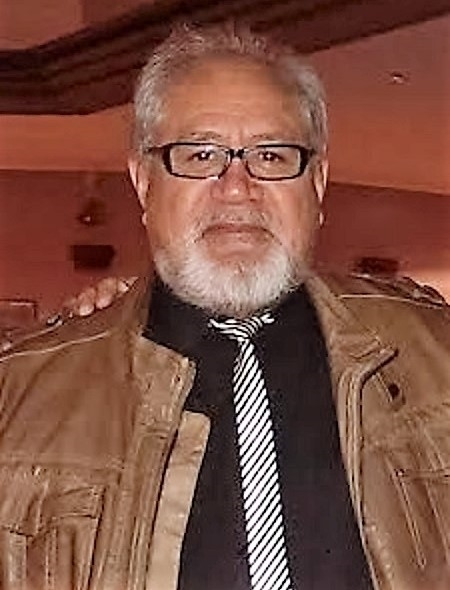

Music has been a huge part of Dave Isaac’s life since he started listening to it intently as a child. Isaac, who grew up in Detroit during the heyday of Motown, says that by the time he was five, he already owned about 100 vinyl records

“I would listen to all the stuff coming from Detroit. At that point in the '60s, Motown was taking over the world, to us. The “Motor City” had truly arrived. I also listened to the blues and jazz music that my dad liked, and the gospel music that my mom liked. Because of my grandmother, I listened to classical music from the Lawrence Welk show, and country music from the “Hee-Haw” television series. I loved it all!”

All that listening helped him develop his musical sensibilities quickly, and he began working professionally in the business when he was just 14 years old.

From that early start, he’s built a career that’s included producing, engineering, mixing, film scoring, and sound design. He’s produced for artists like Marcus Miller, Wayne Shorter, El Debarge, and David Sanborn. He has engineered or mixed for artists like Stevie Wonder, Prince, Luther Vandross, and Eric Clapton. He has programmed (sound design) on tours for artists such as Michael Jackson, Whitney Houston, Madonna, and Earth Wind & Fire among many others, and recently did vocal extraction for Bruno Mars. Dave has three Grammy Awards, and various nominations under his belt.

Audiofanzine recently spoke to Isaac about his production techniques and more.

You’ve been through a lot of changes on the gear side of things and the music industry side of things. What are your thoughts on the current state of the industry, as opposed to where it used to be?

I would say that the industry is caught up in manufacturing talent more than capturing real talent. So someone who, when I was coming up, could do what they said they could do, now it gets done through comping; cut, copy, paste; Auto-Tune; and that kind of thing.

How do you feel about that sort of production? Do you have to do a lot of tuning and time correcting?

I still make the decisions. When I was coming up, you had to decide before you used up a track of analog tape. You had to decide on a sound—you had to decide on what you were going to do. The type of editing and correction we have now wasn’t available. I still make those decisions, but I do them within the confines of Pro Tools or Logic. Someone who is working with me will see that by the end of the night, we can print a copy of their performance, and it doesn’t take me to have to come in later, or the next day, and comp or tune it for somebody to hear it. They can hear it that night, because the majority of the decisions are still made in real time. If I go back and edit, comp or tune, it’s only one word here or there, but I’m not recreating the entire performance.

In other words, you’re fixing little mistakes rather than totally “Frankenstein-ing” the whole thing.

Exactly. Small things. Just like back in the day, when an artist would say, “Can you just punch me in on that word.” The same concept.

These days, do you do more producing or just straight up mixing or engineering?

Now, I’m only a music producer and mix engineer. Producer first, mix engineer second. If there’s any time left, I’ll work with companies to create presets, and develop hardware equipment.

So some company will give you a new plug-in or something and say, “Hey, can you make us some cool sounds for that?”

Yes. I used to program a lot for tours back in the '80s and '90s; I used to make sounds for keyboard companies. I did sounds for a lot of Yamaha stuff, Roland, Kurzweil, and Akai. I also used to A/B sounds with George Duke between his Synclavier and the EMU E4. Man, I miss those days! Anyway, for various artists like Madonna, Earth Wind and Fire, or Michael Jackson, I would come in and make the sounds from their records for their touring keyboards and drum machines. This helped me immensely as a producer years later because I knew how to go in and make the sounds that I wanted before we recorded.

Are you talking about synth programming?

We used to call it sound design or synth programming, and MIDI sequencing. This way, when someone read the credits on a project, they could understand the roles better.

And that’s certainly an area that’s gotten a whole lot more tools for it these days then back then, no?

There are great sounds available now of course, which has made most people lazy now because they’re happy with the sounds that come in the box. This has taken away that job description and also taken away the concept of creating your own identity. Most music sounds like the same instrumentation or synths now.

And you think that’s not a good thing because there are not as many creative new sounds out there?

There are incredible sounds out there like the ones from Spectrasonics and Eric Persing! Killer, right out of the box. Now, if we tweak them or layer them with other synths, man I can’t imagine how far we would go with the sound of music, but nobody wants to spend that kind of time on that anymore. Making their own sound like Teddy Riley, Jam & Lewis, Babyface, or how any of us did.

If you were talking to some up-and-coming producers or recording musician types—and I know you do some teaching—you would recommend not just sticking with the presets? Or maybe start with them, but then try to make the sounds your own?

Yes, exactly. Because if you make the sounds your own and create a hit record, or a couple of hit records, then everyone is trying to figure out how to sound like you. That’s versus somebody saying that’s the sound of a particular keyboard, and they know exactly where to go to get that sound to sound exactly like you.

I guess that exacerbates a problem in the music industry that’s always been there: Somebody comes up with a great new idea, and then everybody copies it until the next new idea comes along. Right? Like the Auto-Tune vocal sound, which has gotten ridiculous.

Exactly, but that sound is normal now. There’s less of it, but it’s still there and acceptable.

What companies have you created sounds for?

In the '80s and '90s, it was just about everybody. Ensoniq, Yamaha, Roland, Akai, and Kurzweil. And then I used to do stuff for Emagic, then Logic when Apple took over.

For the Logic synths?

Actually, presets for the reverbs and stuff like that. And then I started to do it for Universal Audio and Softube.

I understand that your studio is now based around a Focusrite Red 8Pre interface. Why that one?

I used to love Focusrite stuff in the ‘90s when working with artists like R. Kelly and some of the younger hip-hop stuff when hip-hop was starting, and R&B was getting a different low end. And it just so happened that an old friend from Focusrite contacted me to check out the 8Pre, and I liked it. It gave me a lot of flexibility with my other gear, which I can now use more efficiently than before. It was a no-brainer for me because I like Focusrite, and I was looking for some more pieces to help make my gear more efficient because ultimately, I have a very small but powerful setup. Yeah, it helped me free myself and do some things that I haven’t done before. I use all its analog and digital I/O; I can use my Pro Tools HD Native with it, it’s all in this one single-rack space box that I can send out to all those other pieces of gear. It’s a great hub.

How would you describe your approach to mixing?

Well, there are a couple of different ways you can approach a mix: One, you give me a song, and I strive to give you the vision that you seek. It’s not my job to come and change what you wanted or what you saw, unless you know me well and ask me to do that. That being said, engineers nowadays may do that. My job as a mix engineer is, if I get a song from somebody, it’s to make that song three-dimensional to where you can see it, to be able to see the music and the lyrics.

Are you mainly just polishing up the producer’s vision?

I’m actualizing it. The producer may feel like it’s close, but not quite there. "Okay, so let me see if I can get it for you. When they say “That’s exactly how I heard it in my head!”, that’s when I’ve done my job.

Do you usually start with a rough that they give you, like an existing Pro Tools session, or do you zero everything out and start from scratch for the mix?

Nowadays, you take it from where they left off. They got it to third base, and you need to take it all the way home. Back in the day when you’d own a console that was zeroed out, and everything was on tape, you would start it from scratch, but not anymore.

I guess it’s easier the way it is now?

Yes, it’s easier. The only issue now is that they can get married to stuff, and then you have to accept it. Now the other mixing approach, which I follow when I’m producing, is mixing along the way, as I record. I prefer to make it sound the way I want it to as I record it, as opposed to just recording anything—which producers do nowadays—and say, “The mix engineer can change it into something else, ” like he’s Harry Potter.

Do you do all the mixing on productions where you’re the producer?

No. I love to give it to someone else so I can learn sometimes. If it’s something where I truly know what I want and where I’m going with it, then I’ll mix it myself, just for the sake of time. But sometimes, it’s useful to learn from other engineers—especially if I have an interest in what they do or would like to see how they work.

You have worked with some artists who were pretty studio savvy, like Prince and Stevie Wonder. Did you engineer for them?

I engineered Stevie and mixed for Prince.

I’m curious about what Prince was like in the studio? Did he get really involved with the mix and have a lot of his own ideas?

For me, it was pretty simple. I had listened to Prince intently throughout the years. And coming from Detroit, there were certain things that I knew, as far as rhythm and mixing, from Motown and other stuff. By the time I worked with Prince, I knew how to give him what he was looking for. Once I understood the vision of the song, especially with the help of Morris Hayes (his co-producer), and I heard what he was doing, I had enough references to know, “OK, he’s trying to sound like Curtis Mayfield.” “He’s trying to play this kind of music.” I could hear his music; I could hear the influences because I lived them or I listened to them, or I studied them. And, the first time, it was something as simple as him asking to raise vocal or the kick just a little bit. I was shocked because I really thought it was going to be difficult. And then the next time, he listened to something else after we had finished the mix. He listened to another artist, The Roots, I think. Then he wanted to go in that direction. It wasn’t that the mix was wrong, he kept the one mix. But then he wanted to see what it would sound like if we went in a totally different direction, more hip-hop. It was just a matter of understanding his vision,

You were able to anticipate what he wanted?

Yeah, with all the producers that I ever worked with, before I became a producer myself, I could hear what they were going after. I’ve listened to so much music in life, that I can hear a person’s influences right away.

Talk about working with Stevie Wonder.

I recorded with Stevie a few times. The first couple of times, I would be working with another artist, and Stevie would come in as a solo guest. Then, when I moved to L.A., Stevie called me and asked me to record him for one of his own projects.

What was he like in the studio? Obviously, he visualized everything in a way that sighted musicians don’t. How do you think the lack of visual reference affects his music?

There’s a certain type of perfection that blind people have when it comes to music because they’re going by feel and they’re going by hearing, as opposed to sight. Some people are fortunate enough to learn how to play an instrument without looking at it, but someone who’s blind has no choice. But they also learn a certain precision. I had a “full circle” moment during that session with Stevie. It reminded me of when I was young when I used to listen to music with my eyes closed. I would lay on the floor and listen to my Mom and Dad’s speakers, to try to get an idea of what it was like to be in the studio with everyone at Motown. And the singer who amazed me the most was Stevie. He would “see” these things that he was singing about, a girl in a red dress, or the sun, and so on. So at that one particular session, where I recorded his lead vocal, it was in the middle of the night, and it was just Stevie, myself and his bass player. I asked Stevie if I could turn off all the lights so I could see the music the way he would see it.

Wow.

And that amazed him, although the bass player Nathan Watts probably thought that I was about to get myself fired! [Laughs] But it impressed Stevie. Because when I got the mix up quickly to where he could do the vocal, it was based on me just listening and making sure that nothing was in his way sonically. But, as I said, it was full-circle for me because I remember laying on the floor with my eyes closed thinking about Stevie Wonder.

I guess that has something to do with how you talk about visualizing a mix. I’ve heard that you close your eyes at times when mixing?

Exactly, I still do that, and I teach that. I also like listening to music, and mixing in the dark.

What do you tell your students about that?

You’re teaching your brain to see music with your mind and your ears, instead of what your eyes see. You’re teaching your brain to see what’s in the performance, or the imagery that’s in the lyrics, or the personality of the songwriter, the personality of the mix engineer. You’re teaching yourself to see other things than what’s in front of you like a computer or Pro Tools.

Do you visualize the band?

I do, especially if I’m sitting in front of the speakers or have headphones on and I am focused. The mix engineer’s job is to make the performance three-dimensional, so you should be able to do that just by sitting in front of it or having headphones on. But you can also listen to the energy of the soul of the singer, and the energy of the soul of each musician if you listen hard enough. So, that concept has allowed me, even when working with players like Marcus Miller, or Wayne Shorter, or David Sanborn or anybody, to tell where their energy is, what they’re thinking about, what they’re focused on. Maybe you’re focusing on the keyboard. “Don’t focus on the keyboard, focus on the drums.” “Well why, Dave?” “I can tell you that your playing is based on what the piano player is playing, and it would be better if you focused on the drummer.”

Interesting.

You can literally start to hear where someone’s attention is going. But you have to remove your eyes from the equation. I could take it into a martial arts concept, but it’s just ultimately learning how to focus your thoughts to see what someone else is thinking. And you can tell, just by the notes they play, or the notes they don’t play.

Does this visualization also impact the way you pan stuff?

Sure. I can draw your attention to different points of the stage, based on the mix or the levels or the things that happen on each side of the stage. I can make you look, the same way a director does. If they’re shooting a video, they will shoot different sides of the stage, and then when they go into the editing room, they cut it a certain way to keep it interesting. Well, if I remove the visual from the music, I should be able to do that same thing sonically, and make you look, and show you directions—just as though I’m editing a video that you’re going to see.