Although he wasn’t formally trained in engineering, producer/engineer Billy Bush learned to record and mix from two of the best, Butch Vig of Garbage, and legendary producer Rick Rubin. Bush, who has been Garbage’s engineer since the 1990’s, has a discography that also includes artists like Snow Patrol, Jake Bugg, Dweezil Zappa, the Naked & Famous, Fink, Neon Trees and The Boxer Rebellion.

As a kid growing up in Kansas, Bush was originally a guitar player, and was always quite technically inclined. “I was fascinated with the process of making records, ” he says. “I was the guy who had the 4-track and wanted to record our practices, and record our own band and that kind of stuff.”

After moving to Texas, and playing in bands at the University of North Texas, his tech skills continued to grow. “I was always adept at understanding how to make guitars work, stay in tune, sound good. How amps work. I always liked to figure out how things worked.”

Those abilities helped him land a gig as a guitar tech for a touring band, and eventually led to his big break, working with Garbage. We pick up the interview from there.

How did you get the Garbage gig?

I got a call to work with them on their very first tour. I’d gotten a reputation as being able to handle some very complicated scenarios, and was known as being the guy who could figure out anything you threw at him. And I got a call from their tour manager saying they’re really struggling trying to figure out how to do this live. It’s really complicated, a lot of samplers and synths and stuff like that, would you be down with helping with that? I was like, “Yeah, absolutely.” I came out and helped them get things up and running, and we went on a tour. And Butch gravitated to me as someone who understood how technology worked and how computers worked. At this time, around 1995–96, it was at the beginning when everybody was getting their first laptops, before anybody had cellphones.

Hard to remember. [Laughs]

He was like, “We’re going to be doing another record, and I really want to get some sort of digital recording scenario happening. Why don’t you go research what’s the coolest, best thing out there, buy it, learn how to use it and come show us how.” This was before anyone knew what Pro Tools was. He had had experience with the Sony digital multitrack machines, and with Sonic Solutions, and I saw that he envisioned a way to make his life easier, and how he liked to go and manipulate audio. I think he understood that we were on the cusp of a change in how things work. So, at the time, Pro Tools had just come out, and I flew out to the guys at Digidesign, and they showed me what they were doing and what they were planning on doing, and what you could do. So, I bought one of the very first really big Pro Tools rigs. Took it back to Kansas, learned how to put it together and use it.

This was after Digidesign changed the name from Sound Tools to Pro Tools?

Yeah.

So, it was multitrack?

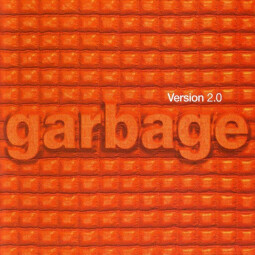

They’d just come out with the 24-track version of it, I think. When we first started using it, it wasn’t 24-bit, it was 16-bit. It was still pretty limited, and Butch’s idea was “I’d like to have something where I can edit drum loops and edit drums, and comp vocals in it, and then fly it back to tape. That was sort of like how he envisioned it. So, I learned how to use it and we started using it as a writing tool when the band started writing Version 2.0, And they gravitated toward it quickly because of how easy it was to write in, and how you were able to change things and all that. And during the course of the writing process, which was over about a month outside of Seattle, I think, Butch realized that he wanted to have me around for a while. So, he was like, “You know what, I’ve always had an engineer every time I’ve made a record. I’ll tell you what, you come up to Madison, and you show us how to use Pro Tools, and I’ll teach you everything you need to know about engineering.” When you get an offer like that, you don’t really say no.

Yeah. [Laughs]

[Laughs] So I was like, “This is my idea of heaven. Sounds great.” And for the recording process of Version 2.0, we were in the studio for 14 months, straight, 7 days a week. And, it was amazing. It was basically like, you get thrown in there, and everything that you possibly think of that you could want to record or try to record. The experimentation level at that time was so high, that every day was like, “Oh we want to try this. Let’s do this.”

Was that 14 months inclusive of mixing?

Yeah. From when we first started really tracking for real to the final mixes being done.

Did you end up doing the whole thing in Pro Tools or did you use tape, as well?

We ended up doing everything into Pro Tools, because we’d gotten into the habit of writing with it. We liked the flexibility that it gave us. At one point we were like, “We’ll dump it to tape, and we’ll actually do the real work there.” But it never evolved to that until the mixing process. When we got to mixing, we dumped it to two 24-track machines, and mixed off of that with 24 tracks in Pro Tools playing back. It was a super pain in the ass.

You were syncing the machines with SMPTE?

Yeah. We had the Micro Lynx and it was like one of those things where it would work flawlessly for a while, and then it just decided not to work.

You obviously learned a lot from Butch during that period.

Yes, back then, literally every time we’d go to record something, I’d have the freedom to approach it in any way shape or form. So, he’d be like, “So this is how I record drum kits, but do whatever you want to.” I’d learn how he’d do it and how he’d approach it, and why he’d approach it that way, and I would also have this flexibility of like, “I read this story in Tape Op about how Glyn Johns recorded the drums on this record. And at some point, he’d be like, “I want a completely different drum sound for this 8-bar section.” So, we’d record the drums completely differently.

Talk about the drum miking techniques you used with Garbage. How many mics, did you use a lot of room mics?

Butch likes things to be very dry, and very much in your face. He doesn’t like a lot of room mics. He likes overheads to be basically cymbal mics, rather than drum kit type mics. It’s not so much about capturing the overall sound of the drum kit, it’s more about capturing the cymbals discretely. The usual setup would be something like, a kick drum mic inside the kick, and then a FET47 [Neumann U 47 FET] outside. And sometimes we’d do it for a drum tunnel kind of thing, where you’d have another drum shell, and packing blankets over it, so you could have the outside mic be a little further back but also not pick up the cymbals. It was very much about separation for him. He wanted to make sure there was as little hi-hat in the snare as possible, and as little crashes in the tom mics as possible. It was very much about placement and mic choice when it comes to how to accomplish all that.

Where would he typically put the snare mic? Was it just one, or top and bottom?

Top and bottom.

SM57s usually?

Yeah, he would gravitate to the 57. I would always switch things up to see what would happen. My favorite, currently, is the new Telefunken handheld mic. It’s a vocal mic, but it’s got a great sound.

It’s a dynamic?

Yeah. So, putting it that way, he had as much rejection of the hi-hat as possible. It would be placed so that the back of it was facing the hi-hat as much as possible. Unlike the typical snare-mic placement with a 57, which is just above the rim, and shooting across the top of the snare drum, Butch liked it much higher, and pointing at an angle, a 30– or 45-degree angle, towards the center of the snare.

Where did he like to place the overheads?

It would depend on how they sounded. It would be spaced pairs, pointing straight down over sort of like the crash area on the hi-hat side. And the other sort of on the crash area on the right side. And then we’d have one for the ride and one for the hi-hat.

And you carefully checked the phase situation, I’m sure?

Definitely. Checking the phase between the overheads and the snare and the overheads and the kick drum. And the snare to the kick drum. And moving things around so everything was in a happy place for all. All the polarities are the same. Which is something you can easily do now in Pro Tools, because you can look at it and kind go, “That one’s inverted, let’s invert it. Let’s just move that one back a little bit and we’ll be fine.”

Can you tell us a couple of interesting techniques you picked up from Butch in terms of tracking? Is there anything that jumps to mind that was like, “Wow, what a cool idea.”

One thing that was very important that he taught me at the beginning was, “Don’t record things sort of cleanly and sort of blindly. Find a sound that you like and commit during the recording process. Don’t wait and do it in the mix.” If you want the guitar to sound a different way, do it then. Don’t be conservative and record a very clean sort of non-threatening guitar sound, if what you want is something ballistic.

That, of course, requires that you have a very specific vision of what you want the end product to sound like.

One of those things that I’ve felt from the start is that when you’re recording, you’re kind of building a house. You need to envision everything before you start laying the foundation. Otherwise you’re going to do something that just doesn’t hold together very well. You’ve got to know what the song is, and what the vibe of the song is going to be. And as you start recording, and you’re putting the foundation down, the drums and bass have to work together in a way that gives room and movement and power to the other instrumentation that’s going to happen. And the other instrumentation has got to work with itself and have room for the vocals—and support the vocals. It’s all sort of building on top of each other.

The guitar sounds on the Garbage albums are very cool. They sound like they have a lot of bottom taken off, and maybe some top, too.

Definitely. Again, with that same sort of concept, the guitars, while needing to be really big and powerful, they can’t really take up a lot of space, because a lot of the songs will have a lot of other instrumentation going on. And it’s really easy to obliterate everything to make the guitar sound cool, if it’s the only thing in the track. But if you want it to sound cool and aggressive and fierce, but at the same time you’ve got 64 tracks of drums and percussion happening, and 18 other guitars, and a stack of 12 vocals happening, the guitars have got to fit. And that was one of the things that we always did. We figured out what frequencies we could have in the guitar sound, and what frequencies were need to translate both the attack of the guitar part and the melodic/harmonic elements of it, but also, what frequencies would convey the power of it. And sometimes, the guitars would sound huge in the track, but if you soloed them, they wouldn’t sound small, but there were like super band-passed. When you add it in with everything else, it sort of fills everything in in exactly the perfect way.

How did you figure out those frequencies? By ear?

It was by ear. It was sort of by instinct. We’d always approach the tracks as if we were mixing it as we went along. There’s be similar things going on so you’d have to have it in a form that made sense. We couldn’t leave things to figure it out in the mix. And the entire process, whether we were tracking guitars or vocals or whatever, we’d be listening to what would be a very solid rough mix. So, you’d be able to tell if something was taking up too much space or clashing with this part or clashing with that part.

I would assume that the stuff you learned from those early days doing Garbage has translated well to when you’re engineering or producing other acts, these days, right?

Definitely. On one hand, the real sort of meticulousness, and attention to detail that I learned early on from that process, really helps when I’m working with bands that are used to working much quicker. And I haven’t been through a process where they made a record that took a year. To be honest, I don’t like taking that long to make a record. But it has taught me that there are certain things I can do to have that level of meticulousness, and detail, but I don’t need to take that long to do it.

These days, nobody has the budget to take that long.

Exactly, and most bands don’t have time in their career to do that. They need to get a record done quickly and get back on the road.

Obviously, it depends on the recording, but what do you find that you typically have to do with home recorded material to make it sound bigger and better?

It’s amazing. The hardest things I think are drums and vocals. Recording drums really well and vocals really well while getting really good vocal takes and vocal sounds, is one of those things that you can’t really fake with really cheap mics and cheap preamps and cheap tools. So those are the two things I tend to find I have to work the hardest on. If somebody records a bass in a DI, that’s fine. I can make that sound great. And a lot of times, in-the-box guitar stuff and keyboard stuff sounds really interesting and cool. If it’s a band, it’s important to make it sound like it was recorded in a space.

Obviously, there’s no way to recreate the energy of a band playing together in a room—but, if you want to make something recorded in layers sound like it was tracked in the same room, what do you use, reverb?

Sometimes that will be exactly what it needs. Everything needs a subtle amount of some room. I’ll either use the Bricasti [reverb] or sometimes Altiverb to add a room. Sometimes a little hint of that will make all the difference in the world.

You have one of those Bricasti Design hardware reverbs?

Yes. It’s surprising because for whatever reasons, its room sounds and studio sounds sound so real, it’s frightening. You don’t really need that much of it. Just put a little on it and there’s enough air around it to give you the impression of a recording in a room.

You use a lot of Waves stuff, too? Tell me about some of the plug-ins that you like?

On the Waves side of things, I love a lot of the sort of modeled stuff they’ve done. Like all the Abbey Road stuff sounds great, and is really useful. From the plates to the J37 to the EQ, the RS56 [passive EQ]. I think all that stuff sounds amazing. H-Reverb is fun too. You can really manipulate the reverb and its time and space constraints, where you can push the early reflections or the tail, and design real reverbs, if you want. I find that’s really inspiring for doing more “sound-designy” stuff.

What else?

One Waves plug-in that I’ve really been amazed by—and I don’t know how it works or what it’s doing—but I find I can use it to make something sound interesting and cool in some way, is the Scheps Parallel Particles. It’s weird, I can take that and make something sound really legit. It’s just amazing how, whatever it’s doing, it makes everything sound better.

What other kinds of plug-ins do you use a lot?

I love all the Soundtoys stuff. Those are all my “go-tos” to make things sound interesting. They make stuff sound cool, they add a little bit of realness to some things. The delays, Crystalizer and EchoBoy and FilterFreak are things that make it onto every single session, in one way shape or form.

Any other favorites?

The U-Audio stuff. I love all that stuff. I’d say that when it comes to reverb simulations, like the BX-20 I really love. I really love the Eventide H910, the tape echoes. The 1176 and Pultec stuff are, again, in every single session. And their new amp modeled stuff is fantastic, like the Ampeg stuff.

Your mixing style was also influenced by Rick Rubin, who you worked with on the Jake Bugg project. Talk about that.

Rick’s up there with people who’ve elevated my mix game to an incredible degree. One of the things that’s interesting about him is that he didn’t want to hear any effects whatsoever, which is exactly opposite to what I was doing in the world of Garbage, which was make everything sound like something you’ve never heard before.

When you say he didn’t want to hear effects, you mean that when you used them, they had to be subtle and sound natural?

Yeah. He didn’t want to hear reverbs. Like a little bit of slap echo was ok, and maybe a little spring reverb, but other than that, he really didn’t want to hear anything that didn’t sound natural. It was all about conveying emotions. I would mix something, he’d come back with notes, and his notes would be abstract, and would take me a second to figure out what he meant. Instead of the usual notes you get back from mixes like, “Can you turn up the chorus vocal 1.5dB and add some 4K to it or something.” It would be like, “It needs to feel a little bit more loose on its feet, right around the feet.” And you’d be thinking, “I wonder what that means?” But if you thought about it, listening to the song, you’d go, “OK, I get it.” The kick’s too loud and the snare’s too quiet, and he wants to hear more of the backbeat, and sort of the glue and less of the four on the floor element of it. But it was more about conveying a feel. And working with him was when I really started getting in touch with the one thing which, to this day, is how I know a mix is done, which is when I feel something. When I feel an emotional response to it after I hear it. If you hear the track hundreds of times when you’re going through and mixing it, you get to a point where you go, “Oh wow, OK, cool. I felt something there.” Then I know it’s really close.

It always seems that at the end of a long mix session, it’s hard to really have any perspective left. But it seems like really good mixers don’t have that problem as much.

It’s hard, because it’s hard not to fool yourself into that moment. And part of is taking breaks often enough so that you’re not sitting there for eight hours bludgeoning your head against the wall. It may take me a few days to mix something. But it’s not like I’ve mixed two 14-hour days without moving. I tried to constantly sort of change the speakers, listen on headphones, walk away from it for a while. Come back, listen to it with fresh ears. When I get to that point where I feel like I’m losing concentration, then I’ll go out and walk the dog or something.

Your ears will recover in like a half an hour, rather than having to wait many hours?

Totally. In five minutes. I’ll go make a phone call. Go to Starbucks and get a coffee, come back. Get some fresh air and some sun and then dive back into it.

Are you doing anything with Garbage these days?

We’re getting ready to go back out on the road in July, so there’s been some sort of prep work on that. And I’ve been doing a lot of archive stuff on getting ready to re-release Version 2.0 as a sort of box set.

With additional material or outtakes?

Yeah, hopefully. I’m doing a lot of the transferring back from analog 1/2”, which is slow, because I have to bake tapes — they’ve been sitting around for 25 years or so— and then transfer them. And then edit stuff together and collate all the different versions of things. We did that for the first record a couple of years ago, and it was a long but really fun process to go through all the material and find the original versions, and transfer them and get them all archived at 24-bit, 96 kHz, sort of hopefully, future-proofed versions.

Talk about baking tapes.

Yeah. After a lot of research, it turns out one of the best things to get is one of those things that are designed to make potato chips, they’re basically dehydrators. There are a couple that happen to be almost the same size as the 2” or 1/2” analog tape. So, you can set it for a specific temperature and you put the reels of tape in there and let them bake for 10 or 12 hours. The baking process, what it does is makes the formula that keeps the tape together sort of re-active. If you don’t bake them, and you put them on the reel, a lot of the tape will start to come apart.

Like flaking off?

Yeah, totally. It will like physically come to pieces. But if you bake them, then it’s amazing, because it sort of rejuvenates the chemical compound that keeps it together. And then it plays back perfectly.

Thanks, Billy!

You’re welcome.