If you want to start making up melodies and bass lines from chord inversions, as I promised in the last article, we must first address the thorny issue of consonance and its evil twin, dissonance... which, by the way, is crucial to harmony!

Why is it thorny, you ask? Well, simple because the perception of what is consonant and dissonant is extremely subjective and depends on multiple personal historical and socio-cultural factors. Not to mention that the human ear has never ceased to evolve: what is considered “pleasant” to a “Western” ear in the 21st century would probably not have been to a Western ear in the 18th century. Nor would it be to a modern “Oriental” ear, even if we are currently experiencing a sort of musical globalization.

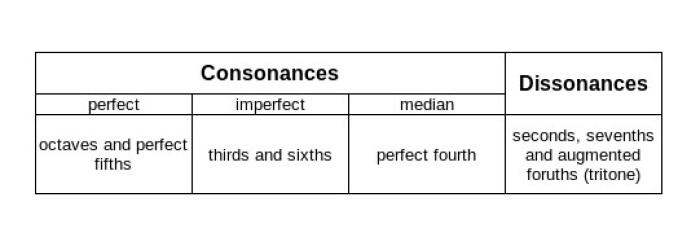

Consonance and dissonance table

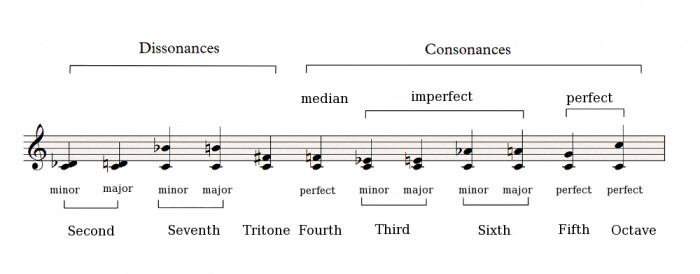

With this brief introduction, let’s take a look at the table below to see how intervals are split into consonant and dissonant, according to contemporary Western standards.

- Minor second 00:02

- Major second 00:02

- Minor seventh 00:02

- Major seventh 00:02

- Tritone 00:02

- Perfect fourth 00:02

- Minor third 00:02

- Major third 00:02

- Minor sixth 00:02

- Major sixth 00:02

- Perfect fifth 00:02

- Octave 00:02

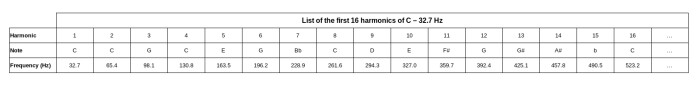

We must add to this table the harmonics of a fundamental sound (for a brief recap of what harmonics are, refer to the 4th article of the Sound Synthesis series). Do note that we are talking about natural harmonics here, not “tempered” ones, like on a piano. This is something I’ll come back to in a future article.

From this table we can conclude three things.

Consonance according to the harmonics

The first is that an interval is all the more consonant if you combine its fundamental with the closest harmonic. The most perfect consonance is the octave, then the perfect fifth, the major third, etc. While this observations may seem to give some sort of scientific basis to our current perception of consonance, remember that this perception is based on cultural elements. Incidentally, the fourth (F in this example) isn’t part of the natural harmonics of a note!

Consonance according to note position

And now that we mention the fourth, the second lesson to learn from this classification of consonances is that, depending on their relative position, two notes don’t have the same consonance relation between them. Hence the C-F fourth is considered a “median” consonance, while the F-C fifth is a perfect consonance.

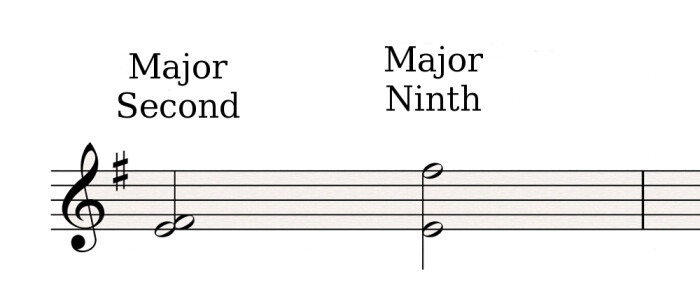

Likewise, while the E-F# major second is a pretty rough interval on the ear, the E-F# ninth (an octave higher) can produce a very pleasant sense of openness nowadays.

The dynamics between dissonance and consonance

Finally, the last thing to observe is that the intervals that seem consonant are those that sound “pleasant” to our ears and don’t require any particular resolution. In fact, by a mirror effect, what characterizes a dissonance is precisely the tension that you feel when you hear it and the need for resolution that it prompts in you. Like the example of the dominant seventh chord which seems to desperately call to be resolved to the tonic. And it is precisely this tension that provides dissonant intervals their dynamic character, contrary to consonant intervals which sound “static.” At the same time due to this static nature of consonant intervals they often end up being the strong beats of the harmonic rhythm (the so-called “stable” chords in articles 9 and 10 are based on consonant intervals).

You could even say that ever since we started playing notes simultaneously in the Western system (yes, it’s important to insist on the cultural aspect of this!), we have tried to alternate between dynamic and static, or dissonant and consonant, intervals. And we’ve done this to emphasize the strong beats of the melody and, thus, articulate better the musical discourse.

In the next article we’ll study dissonances in more detail, especially how to resolve them.