One of the main functions of mastering is to make a mix transportable: In other words, it should sound good over any playback system

But what works against this is that playback systems vary wildly. Although we no longer have to worry about all the violence that happens to a signal courtesy of analog playback media (cassettes and vinyl, which offered a nearly infinite number of possibilities to screw up sound), speakers and their associated enclosures are like very mischievous equalizers. For a mix to be truly transportable, it needs to sound “right” when played over:

- Great audiophile systems with flat response, superb definition, and state-of-the-art speakers.

- Boomboxes that have the “MegaGigaSuperBassBoost” button pushed in, which hype the speaker’s low end to an absurd degree.

- Boomboxes that don’t have the “MegaGigaSuperBassBoost” button pushed in, resulting in a low end that’s thinner than Kate Moss on a hunger strike.

- Earbuds on portable music devices, whose response is basically luck of the draw.

- Car radios. Let’s not even go there, even though we have to.

- Tabletop radios, which have the same type of issues as boomboxes.

What do all these different systems have in common? Speakers (even if they’re miniature versions that fit into ear buds). How do we compensate for differences among speakers during the mastering (and for that matter, mixing) process?

Welcome to Flatland

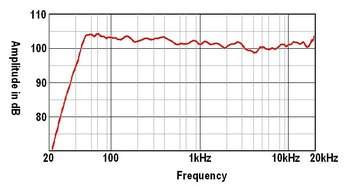

Edwin Abbott’s Flatland is one of the greatest mathematical fantasy books of all time, albeit in an admittedly uncrowded field. But when it comes to speakers, “flatland” is just that: A fantasy. Look at the response curve for even the finest speakers that money can buy, and you’ll see something that approximates a relief map of the Alps. This response (see Fig. 1) undergoes further degradation when interacting with the listener’s room, which is seldom acoustically treated; but let’s pretend that’s not an issue, as it multiplies the variables into the world of Really Really Big Numbers.

Fig. 1: Here’s a typical frequency response curve for a high-quality, pro audio-oriented two-way speaker with active crossover. Although it’s anything but flat, this is actually better than average – yes, this is what you’re up against.

Differences among speakers exist over their entire range: Lows, mids, and highs. So, over the years, mastering engineers have recognized that the only want to deal with this madness is to create a recording with the flattest, most “average” response possible. That way, it will sound only a little bit “wrong” over every system, rather than okay on some systems andway wrong on others. (The exception is that of the audiophile with the really flat system – who after putting the requisite time, expense, and effort into assembling a great system, should be entitled to the best possible sound.)

It’s difficult to create a truly average midrange response, because that’s just one of the places where speakers exhibit significant differences. (An aside: I always get a kick out of speaker reviewers who breathlessly exclaim that a particular speaker “revealed things I’d never heard before in my favorite recordings!” This isn’t surprising, because any speaker will reveal things you’ve never heard before, as it’s basically EQing the recording differently.)

High frequencies are a different matter. The energy in real music tends to drop off fairly rapidly above 5kHz, so really, what we want is a “sensation” of brightness. You’re not going to get the huge peaks caused by notes piling on one another, because there just isn’t that much energy up there. A little bit of a boost in the “air” range above 10kHz will do wonders for making a mix transportable, as the tweeters open up a bit more. As a bonus, most playback systems have a treble control that can be trimmed or boosted according to the listener’s preferences, based on their acoustics and how shot their hearing is from going to too many concerts without hearing protection.

BASS IS THE PLACE

Perhaps the most crucial frequency range for making a mix transportable is the bass range; there are several reasons for this.

Working Transportability into the Mix

Ideally, your mixes should already be pretty close to perfect before they get to the mastering engineer; and there are some steps you can take while recording and mixing to make the master more transportable.

Instruments with lots of low frequency content, like kick drum and bass, will not translate well over systems with poor low frequency response. To allow them to be heard on bass-shy systems, use midrange EQ to bring out pick noise in the case of bass, or the “thwack” of a beater with acoustic kick. With electronic kicks, there are a variety of ways to accentuate a “click” at the beginning of a note. Psycho-acoustically, your brain will tend to “fill in” the sub-harmonics.

Speaking of sub-harmonics, some sub-harmonic, sinewave-type basses (as often used in drum 'n’ bass) will never make it through small speakers. Try using a waveform with more harmonics, and close down a lowpass filter to get a bassier tone – but which still has some harmonics present.

Finally, although it’s been said a million times before, let me be number 1,000,001: Acoustical treatment is your friend. You can neither record nor mix sounds properly in a room where the acoustics are adding the equivalent of a random EQ with insanely steep peaks and notches. Although a mastering engineer will try to deal with this, it’s not easy and not always successful.

Speakers tend to have the hardest time maintaining a flat response below about 80Hz. Here we’re up against the laws of physics, as bass frequencies have really long wavelengths and to re-create them, you need to push a lot of air. Speakers that fit in the average living room, or boombox for that matter, simply can’t push enough air at really low frequencies. This is one element that separates the big bucks speakers from the pretenders: How low they can go without giving up. This is also why many devices have bass boost switches, although that’s not quite the same as having “real” bass. An analogy: A woman puts on great eye makeup that makes her eyes look bigger, but really, they aren’t any bigger.

To make matters worse, we have two other bass range issues. For one, the bass response of our ears falls off at lower volumes (the infamous “Fletcher-Munson Curve”), so our ears’ deficient frequency response interacts with the speakers’ deficient frequency response. The second is in the recording itself. Unless the studio has really great acoustics, or all instruments were taken direct, there will likely be frequency response anomalies due to room acoustics that cause peaks and dips in the bass range.

So in a worse-case scenario, the bass peak in the recording process doesn’t get caught while mastering, and plays back though a speaker system that has a resonance at that frequency, which interacts with the room resonance in which the speaker lives. Nasty.

That Sounds Hopeless and Depressing. What’s the Solution?

There is no solution, so you’re correct in feeling hopeless and depressed. But you can try to come as close as possible to the ideal. If during mastering you can smooth out the bass response to have no significant peaks and dips (except where you actually want them, like a big peak on a techno kick drum), you’ll have gone a long way toward making a transportable master. It’s even better if you can take care of some of these issues in the mix (see sidebar).

Because our ears’ response gets iffy in the bass range, it can really help to have some visual feedback as to what’s going on in the bass range. No matter how good an engineer you are, it’s really hard to quantify a 1.5dB peak at 72Hz solely by listening. I find a good spectrum analyzer that can display an average response is extremely helpful. Why average? Because there will always be natural response peaks and dips. What we’re looking for is a pattern of build-ups and anomalies which, if played back through a system with a peak or dip at that same frequency, will exaggerate the problem even more.

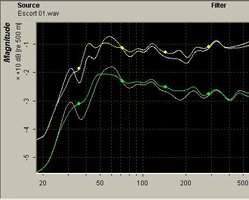

My favorite tool these days for fixing this type of problem is the Har-Bal EQ/mastering program. It provides a very unambiguous look at the bass end, and you can use a simple “pencil” tool to draw out peaks and dips, thus smoothing out the low end (Fig. 2). Since doing this, my mastering clients have all – without any prompting – commented that the mixes are more transportable. Granted there are more factors that just bass response that contribute to making a mix transportable, but bass is an important factor.

Fig. 2: Here, the Har-Bal program has been used to smooth out a song’s bass response; for clarity, the window has been trimmed to show only the region below about 500Hz. The upper gray line indicates the original peak response, and the lower gray line, the average response. The yellow line indicates the peak response after “drawing” a smoother bass response, while the green line indicates the average response after smoothing.

Fig. 2: Here, the Har-Bal program has been used to smooth out a song’s bass response; for clarity, the window has been trimmed to show only the region below about 500Hz. The upper gray line indicates the original peak response, and the lower gray line, the average response. The yellow line indicates the peak response after “drawing” a smoother bass response, while the green line indicates the average response after smoothing.

Other Tools

Another great mastering tool that helps compensate for speaker anomalies is a good multiband compressor (Fig. 3). Some subtle midrange compression can bring down peaks and raise valleys that might otherwise be emphasized or de-emphasized by a speaker. In the high end, you can add no significant compression, but just boost the overall level a bit. Meanwhile, in the 300–400Hz range, you can lower the level a bit (without compression) to “tighten up” the sound somewhat, as that’s often where you’ll find a bit of “mud.” Meanwhile, adding compression in the bass range helps even out the response.

Fig. 3: The Multiband Dynamics Processor in iZotope’s Ozone has been set up to add some mild compression in the low end; this smooths out the bass response a bit, which helps make the mastered recording more “transportable.”

Eventually, through proper use of equalization and dynamics control, it’s possible to create a master that keeps unwanted peaks and dips under control. And when you’ve accomplished that, you’re in good shape.

As a final reality check, it’s worth playing your master over varying systems just to make sure you’ve come as close as possible to the ideal. If your mix sounds a little fatter than usual on systems that normally sound a bit on the thin side, thinner than usual on systems that normally sound annoyingly muddy, and perfect on really good systems, great. No matter what speakers the recording plays back over, you’ve probably done about as good a job as you can do.

Originally published on Harmony Central. Reprinted with permission.