For a long time the mastering process was a mystery for most musicians, even those with studio skills. But thanks to all the information now available online, it's a lot easier to learn about how mastering works. That and the availability of affordable mastering software has led some recordists to start dipping their toes into the world of DIY mastering. The question is: Is it a good idea?

The aim of this article isn’t to teach you mastering techniques (we did that in great detail in our 22-part mastering series), but to point out the pros and cons of doing it DIY, so you can make an informed decision as to whether it makes sense to master your own material.

Why DIY?

If budget weren’t an issue, it’s a safe bet that virtually everyone would opt to send their tracks to a mastering engineer. The problem, of course, is that budget is a big issue for most people. Professional mastering is expensive. Even a modestly priced service is probably going to set you back close to $500 for a full album. A top-of-the-line mastering engineer could cost way more.

So the biggest advantage of doing it yourself is financial. At least in the short term. The only money you’ll have to lay out is for any software or additional gear you might need. In the long term, though, the benefits are more questionable, because it’s doubtful your album will sound as good or hang together as well as it would if you had brought it to a pro.

What you can and can’t do

As a DIY mastering engineer, you face a number of disadvantages: First, you’re most likely working in a room that has untreated acoustics, which can skew the way you perceive frequency content. Decisions you make based on what you hear may not translate well to other systems.

Secondly, commercially available mastering engineers are usually quite experienced — that’s generally all they do — whereas a DIY mastered is starting from square one. And, of course, it’s unlikely you have the high-end outboard EQs, pristine signal paths, and super accurate monitors that you’ll find in mastering studios.

That all being said, there are some aspects of the mastering process that you can do very well in a DIY environment, just using the expertise you’ve gained recording and mixing. Most notable is sequencing the album. That is, putting the songs in the order you want, trimming the beginning and end, adding fades and crossfades, and setting the spacing between songs.

Adjusting the relative levels between the songs is also quite doable. It may take some trial and error, and some jumping back and forth between songs to compare levels. It might even require burning test CDs for listening on other systems, but anyone with decent ears and the right software can do it.

But while you can pretty easily match the relative levels between your songs, making them loud enough to compete with commercially available music is trickier. You have access to brickwall limiters, which can raise the overall level quite a bit by reducing the peaks first. But if you over do it, which can happen pretty easily, it makes the music sound one-dimensional and fatiguing (see our series on the Loudness Wars).

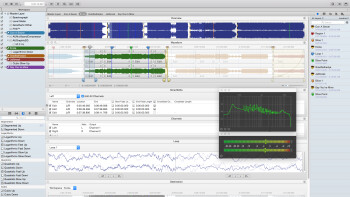

This is not to say that it’s impossible to get your music loud on your home system. Mastering software like iZotope Ozone and Audiofile Engineering Triumph and the Project Page in PreSonus Studio One Professional, give you the tools to do it, but a professional will have more experience, know more techniques, and have access to a bigger selection of processors.

Mind your Ps and EQs

In addition to balancing levels, a mastering engineer also aims to make the songs in an album as consistent as possible, frequency wise. That, of course, is done with EQ, as well as multiband dynamics. In an untreated room on prosumer gear, you’re at a great disadvantage compared to a pro mastering engineer.

Again, the issue of experience comes into play. EQing in a mastering context is a more subtle process than what you’re probably used to in the mixing realm. It’s more micro than macro, entailing a lot of subtle individual cuts and boosts at multiple frequencies, through a variety of filter types.

|

If you’re a Studio One Professional user, you’ve got a built-in mastering environment: the Project Page

|

Because mastering is done to the stereo mix, rather than on individual multitrack tracks, the EQing you do impacts everything to some degree. For example, applying low frequency cuts to tame an overly boomy bass guitar, will also impact the vocals, so it’s always a balancing act.

Trying to target individual elements within the stereo mix in order to fix EQ or level imbalances requires savvy processing chops. Mastering engineers have ways of dealing with such issues (sometimes using M/S processing if the element in question is panned to one side or the other), that the neophyte probably wouldn’t even know about.

On the flip side, those doing DIY mastering (presuming they also did the mixing) have direct access to the multitrack DAW file, and can fix issues they discover in mastering by reopening the mix, addressing the problem, and bouncing out a revised mix.

Last words

The bottom line is that it is possible to master your material, and depending on your engineering chops, and what you’re using the music for, you can do a credible job. Still, if you can afford to go to a pro for your mastering, your final product will likely be more polished.