Tom Holkenborg (aka “Junkie XL”) has had a long and successful music career as a producer, recording artist, and remixer — and over the last several years he's become a top Hollywood film composer. He’s scored big-budget movies including Mad Max and Divergent: and he’s now working on the music for Batman and Superman.

But he’s also had a long-time interest and talent for music education, and has been involved with helping shape a university-level program in his native Holland. Holkenborg feels strongly that it’s incumbent upon successful musicians to give back to the music community, and he’s doing that in a very substantial way through the release of Studio Time with Junkie XL, a free 20-part YouTube video series in which he shares his production and film scoring techniques.

Audiofanzine had a chance to talk to Holkenborg about the videos, his scoring work, his DAW of choice and more.

What made you decide to create a tutorial video series?

For me it’s actually a three-step process how I got there. Basically, when I was 18, I worked in a music store and I found out that I was pretty handy in explaining synthesizers, sequencers and computer systems to clients. So pretty soon in that time period, I got noticed in Holland by brands like Yamaha and Roland. And they were like, “Would you like to do a demo for us?” And in Holland we have what’s like a super small version of the NAMM. And I would go there every year and I would demo a certain product or a software program or a synthesizer. So that was my first experience actually in explaining software and gear to other people in a fashion where they could pick up what was the most important thing they needed to take away from that program or hardware.

What happened next?

Now the second time this happened was in 2002 when I got approached by the president of one of Holland’s bigger music universities who said, “We’re interested in having you attached to our study program, and maybe you can help us setup what you think is the ideal program.” So I did that for eight years, putting together programs for students. I would give master classes and I would explain everything that I know about myself and the mistakes that I made.

Was it a music production program?

It was called music media, and it was very wide in setup. So from people who wanted to be CSound or CapyTalk [Kyma programming language] programmers to do sound design to people who wanted to be film composers, and everything in between.

So it was all based around electronic music, but with a lot of different types of students?

Exactly. And for me, that really sparked my enthusiasm for education. And that program, like many of these programs around the world is quite expensive. And then we get to this YouTube tutorial series. What I wanted to do is make something that was not just a quick soundbite that you can quickly watch for a minute on your iPhone. I actually wanted to create episodes with good production values that really go in depth about how I work, and what people can take away from it for their own career and their own education. And that’s why these videos are quite elaborate and quite long. But I really go into detail and I share as much as I can that I’ve learned over the years, with the people who watched this, and for free. Because I feel that education should be for free or little or no money. And we want to basically keep going with this.

How many episodes are there?

We have roughly 20 episodes. And after those 20, we’re going to gather a lot of feedback from the people who have watched them, and we’re going to see how we can make it better, and how we can do it different, and what would you like to see in the next 20 episodes. And then we’ll release a whole bunch of new ones, and we’ll start releasing them again every week.

That’s why there are only 10 out now?

Yes, we’re still going at a pace of once a week, and we’re actually going to take a break. I think today is the last one for six weeks, because so many people go on holiday, in the weeks to come, and it doesn’t really make sense to release them, and you lose traction. So we’ll pick everything back up when colleges start again, which is like late August, or the first week of September.

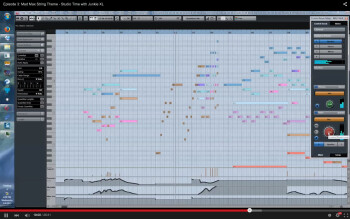

A number of the first episodes are focused on your work on the Mad Max movie. When did you work on that film?

It started August 2013 and it went all the way until April of this year.

How many movies have you scored before this and was Mad Max the biggest?

I’ve scored a bunch of movies over the last three to four years — it really started taking off about three years ago. I’d say the movies I’ve been working on have all been at about the same level of importance, or the same amount of box office. So it’s Divergent, it’s 300: Rise of an Empire, Mad Max. I’m working now on Batman and Superman, which is going to be a really big one. And I also did Black Mass, which is a great crime movie with Johnny Depp and Benedict Cumberbatch. That comes out in September.

Congratulations. It sounds like your scoring career is really taking off.

And the counterpart of that is that it’s even more important to release these free videos.

Let’s talk more about the content of the videos. You did a whole video about your DAW template and setting it up. It was all based around Cubase, but I assume there are lessons there that people can extrapolate to other DAWs?

I’m not doing tutorials on the other software programs because at this point, I’m not using them. So I would say the videos that are made are purely based on how I work and how I structure things. And I think that if other composers would start doing that who use Logic, or other composers that are purely using Pro Tools, then you would get these really complex, colorful lectures from three different composers working with three different software programs. And if students watched that they could say, "Oh, interesting, Junkie works with Cubase, but Brian Tyler does everything in Pro Tools, let’s see what the difference is.”

That would be interesting.

But having said that, these DAWs are all capable of the same thing, more or less. So if you see a tutorial in Cubase, that could spark a whole set of ideas that you could eventually do in Pro Tools or in Logic. It’s never either, or.

You’ve changed DAWs several times during your career.

In the beginning I worked with Cubase. Then in the 90's I switched to Logic. Late '90s switched back to Cubase. The beginning of the 2000s, I went to Pro Tools, and then 2010 I switched back to Cubase. I constantly switch back and forth, depending on what software program at that point in time gives me the best [features]t.

And what is it about Cubase that made you choose when you last switched?

There are a couple of things that are not necessarily unique to Cubase, compared to other DAWs. I used to work a lot in Pro Tools. I mixed everything in Pro Tools. But when it comes to MIDI, Pro Tools is not as advanced as Logic and Cubase. At the point that I switched to Cubase, I did a very thorough A/B comparison between Logic and Cubase. And at that specific point in time, Cubase had more interesting options, especially where it comes to the mixers. Logic at the time was very limited in terms of how to mix in surround, set up busses, record stuff back in, and setup complicated routing structures, and stuff that I used to do in Pro Tools now allowed me also to do that in Cubase. At the moment I switched to Cubase, it was 32-bit floating point, and none of the others were.

How did that help you?

It allowed me to program and do whatever I wanted to do, and if I had distortion or was overdriving the output, then you just pull the master down and everything gets recalculated in the mixer and plug-in window, and all the distortion is gone. So, when I switched to Cubase, at the time, which was like 4 years ago, almost; that was the only DAW that had the floating point thing going on in the mixer, and therefore, technically distortion didn’t exist.

So the big advantage of having 32-bit floating point is that if you clip, it can recalculate?

Yeah, that’s it. So, the idea is, if we keep it very simple, let’s say I have eight beats in my track playing at the same time. And let’s say my first instrument track is a very hefty rhythm. And let’s say that rhythm is almost 0db. And if I’m going to add 10 more layers of drums to that original drum layer, and I don’t adjust the faders, everything will be overdriving the output, clearly creating distortion. In a DAW, that doesn’t have a floating point mix engine, you basically have to go to all the individual faders and pull them down one by one until the distortion is gone, until you have the normal headroom in your output again. Now in Cubase, you just need to pull down the master fader, and it recalculates what that would mean for all the other individual tracks, and your distortion is gone.

And that allows you to maintain good gain staging.

Yes.

I noticed that you were on a Windows computer. Have you been on Windows since you went back to Cubase? What made you switch off the Mac?

I tried Cubase on the Mac. It wasn’t a happy marriage. The VST plug-in format is written for PC, not for Mac, so it’s way more efficient on a PC. Things like Logic and Pro Tools are natively built and constructed for the Mac, and you’ll see they’ll work way better on the Mac. I mean, Logic you can’t even run on a PC, but Pro Tools you can. But it all seems to make more sense that a program that’s developed for a platform is the one to go for.

For your film work are you always working in surround, or do you only mix things into surround later in the project?

I write in surround. I write original material in the surround speakers.

And why do you do it that way? Does it then translate better when you get to the final part of the project?

No, but I think we’ve gotten to a point where the surround speakers can be used way more creatively than just a little bit of reverb or whatever. And more and more directors are interested in doing really crazy stuff with the surround. And now we’re also talking 7.1 as well. So you have so many speakers that you can do stuff with. So what I usually do when I work on films is that I have my solid stereo mix, and that has reverb that goes into the surrounds, and then I create extra layers of music that specifically go into the surrounds or to the [other] speakers. And then with the mixing engineer that mixes the whole film, which is called the dubbing mix process. That’s where dialogue, music and sound effects come together and get mixed in a perfect balance.

One mix engineer for the whole process?

Usually every discipline has its own mixer, so there’s one mixer for all the dialogue, there’s one mixer for the sound effects, and there’s one mixer that does all the music. And the three of them sit together behind this massive console to mix the movie. And, they work together, minute by minute until everything is in balance.

Is your music mix not completely locked in by the time you bring it to them, so you can still move stuff around?

Completely. You bring stems. So when I say, “OK, my music is completely mixed, ” we’re talking 40 to 50 5.1 stems that play at the same time at unity [gain], and that is your mix.

Do you always write to picture?

Always. I do write music sometimes based on a script, or based on a conversation I have with the director, but then as soon as the picture becomes available, then everything translates to the picture. But sometimes it’s interesting to write a theme, basically from reading the script. I’m actually working on a movie right now — I can’t talk about it — that I haven’t seen the picture yet, because it’s being shot at this point. But I’ve had the script for half a year already, and after reading it, I get all these ideas for melodies and sound, purely based on the script, I haven’t even seen the picture.

And then sometimes, if you were doing that, and you saw the picture, might you go, “Oh wow, I was imagining that very differently, ” and then you’d want to change the music?

Yeah, but you know what’s funny: Usually my initial hunches are right ones.

That’s why you’re doing well in this business, I guess. [Laughs]

[Laughs] It’s all about the initial hunch.

Go with your gut.

Right.

I noticed that there’s a lot of orchestral stuff going on in the tutorials that focus on the Mad Max score. I know you were initially renowned as an electronic music guy, but have you always worked with orchestral instruments?

I come from a music family where I had a traditional music upbringing. And I played violin at a young age and classical piano, so it’s part of my DNA. And later, when I started to get more and more into film scoring, it was a little rusty in the beginning, but then it was like “Oh yeah, that’s how that works, ” and “Oh yeah, that’s how that works.” And so it all starts coming back and it triggers your imagination, and you start studying more, and you start analyzing certain classical pieces from the past. It’s like, “Why was that so great?” I remember it sounding great, but why? And you look into that and you study a lot of material. For me, there’s a lot of studying and analyzing involved, which is something I really like.

Do you analyze everything in a traditional music framework?

In music, there’s a lot of math involved. Look at a sequence of numbers, like: 2, 4, 8, 16, 32. When you see those numbers in a row, they make sense. And everything that’s logical and everything that makes sense is what people like. That’s why people like symmetry. And that’s where it becomes interesting, is if there’s symmetry, but something is off in the symmetry that makes it special. And that’s when emotion comes into play. So people like to see symmetry, and people like to see logic, but if you alter the logic and the symmetry in the right way, then it becomes very attractive. It’s the same with how people judge whether someone is pretty or not pretty. Usually, people pick someone who has symmetry with just a few things off. People usually judge those people as the most beautiful. Or pieces of music as the most beautiful. So a pop song that follows all the rules, it’s great, but if it has a twist in it, then people love it.

Are your scores typically played by an orchestra?

Yes. I mean, it’s a question of budget. I have worked on alternative films in the past where the total budget for the film was like $20,000, and you can’t even record an orchestra for less than $150,000. So then there’s a no-go and you have to make samples sound as good as you can.

Do you think one can do a pretty decent job with orchestral samples only and no live players?

Let me tell you how this works. If you buy sample libraries with certain articulations. So lets just speak to the basic ones: long strings and short strings. So if you write a piece of music just for long and short strings, you could make them sound really natural. But the thing is a real string orchestra can play a million more articulations than just long and short. And those are almost impossible to program. So that’s why you constantly go for a real orchestra, because you can create colors that you simply can’t program.

Film scorers always talk about the crazy deadlines, the picture always changing, and having to constantly revise the music. For you, what’s he biggest challenge of being a film composer.

There are so many things at the same time. You need to be a very original, inspiring composer and musician. You need to be a very good manager, not only of your time, but of expectations that live with the studio and the director. You need to be very good at networking. You need to be very sociable as a person. You need to withstand criticism like nobody else, and you need to be able to re-write a certain theme up to 20 times because people are not liking it, or it’s not fitting the picture according to the director. Or you’re dealing with the picture changes. And when the movie gets close to the deadline, everybody gets nervous, and sometimes they change the whole movie around. They change composers at the last moment, they change picture editors at the last moment. So, there’s a lot of stress in this profession.

It’s kind of famous for being stressful.

But those are the downsides that people usually bring up first. I do it usually the other way around. My focus is the pleasurable side of being a film composer, and that is that you work with these amazing creative people, and that you usually work with studios that are full of very smart people, they really know what they’re doing. And I’ve been fortunate to work with great directors, with great studios, great movie products, and for me, by an arms length or more, it’s the upside that makes it great.

[Watch the video series Studio Time with Junkie XL.]