Grammy-winning mix engineer Dave Pensado (Beyonce, Michael Jackson, Elton John and many others) is one of the tops in his field. Five years ago, he and his manager/business partner Herb Trawick created Pensado’s Place, an audio-themed Internet-based TV show. A mixture of interviews and tech advice, the show has grown to become immensely popular in the audio world and draws large audiences every week.

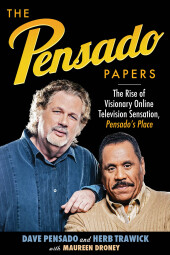

Pensado and Trawick recently released The Pensado Papers (published by Hal Leonard), a book that chronicles the rise of the show, offers advice on how to succeed in the digital media world, and sprinkles in plenty of studio tech tips. We recently had the opportunity to talk to Pensado and Trawick, and we not only discussed the show and the book, but a lot about mixing, the impact of technology on the mixing business, how to develop a career as a mixer, and more.

Dave, what percentage of your work life is now taken up by the show?

Pensado: Well, I don’t look at it that way. It’s all so interwoven. When I’m in the studio, everything I do contributes to the show. When I’m doing the show, everything about the show contributes to my studio life…I would say probably 80% of the time, I’m physically in the studio, and 20% of the time I’m devoting towards the show…Herb does all the major work. Herb puts more time in for the show than I do for mixing. He’s the person that makes it look good, the person that makes it popular. All his ideas come from a point of giving the viewer value and education is very important to both of us…Herb has a team of people that execute. Herb is always trying to figure out a way to keep the show free. That’s important to us, and it’s getting more and more difficult.

Trawick: That’s for sure.

How many views do you get on a typical episode of Pensado’s Place?

Trawick: It changes, but our specific audience monthly is between 500,000 and 600,000 people. If we add in our affiliated sponsors and their audience reach — it starts to approach about a million.

The book chronicles many things including how the show has developed into the force it is now. What was your motivation for writing it?

Pensado: We did the book to kind of solidify and quantify and organize our own thoughts: “What the heck just happened?”…The book is not necessarily about the show, it’s about two different lives from two different places in the world and how our experiences and our past triumphs and our past failures led us to the point where we were able to create something that people seemed interested in.

Trawick: The book has tips and tricks that are technical, from our guests and from Dave. It’s a story of redemption. It’s career advice. It’s a comeback story, it’s a story about partnership. It’s a story about digital new media and how to take it on and go from two guys who don’t do this at all to two guys who have built something. We start our fifth year in January and the extent of things that have happened because we decided to take this on and be forward facing and forward leaning, is stunning, in terms of its scale and size.

Dave, you mention in the book that many of the recordings that you’re getting these days that have come from home-recorded projects are not always up to the level quality wise that you would like them to be. What are the typical problems that you find?

Pensado: Well. Let’s look at a parallel — photography. A person might buy a 5-mega-pixel camera and start taking pictures. Let’s say a magazine has to publish those pictures. There are certain things that that person might not have been exposed to, and it just depends on their level of commitment to that discipline. Audio is the same way. There are so many wonderful tools available to everyone, sometimes for free and most of the time at a very reasonable cost, that the entry level, in terms of actually doing something is very low. There are different skill levels. Now I don’t like to use the terms “good” and “bad” because ultimately it’s about the music. So my issues are not so much about bad recording, as they are with, I hear the energy, I hear this wonderful, wonderful idea, and the execution of that idea makes it a little difficult for me to bring it to its full value and to give it its full weight in the process of mixing.

In that case, what do you do?

Pensado: I have no problems, by the way, if I think something can be enhanced, whether it’s was done by a top tracking engineer or by a guy that just started yesterday. I have no problems calling him up and saying, “Hey man, if you can just do this like this, I can take this to another level.” Mixing is a team sport. That’s kind of the way I look at it

Do you think the problems are worse in projects not done under the auspices of a producer?

Pensado: I think so. Here again, I’m of the opinion that the idea is more important than the execution. And I think that if we go back to photography, back when the 1-megapixel camera came out or the half megapixel camera came out, it wasn’t capable of producing a lot of great work. But now those people, after 20 years, they’re moving up to 5 megapixels. They have SLRs, they have interchangeable lenses, they have Photoshop…The same thing is going on in the audio space. The quality of the work that I’m given by non-pros is clearly better this year than it was five years ago. And I think that due to the access to information on the Internet — not just our show, there are multiple sources that are incredible — this will be a non-issue in a few years.

Trawick: It’s also a strategy decision. There are some people in the realm where Dave is as a mixer, sort of in the top 1-percentile, who might not accept work from what I call Internet mixers and non-pros. They may just want to do major-label projects. I believe as a manager that’s a strategy that’s limiting. I think that is not as stimulating for a mixer, and I think you miss a lot of opportunities. And so if you’re going to open up your opportunities to people who are not doing things for major labels or major film companies, you’re going to get a different variety of expertise. And what you do is you just deal with it, it’s just that simple.

Prior to the digital age, when engineers were coming up, there were a lot of commercial studios, and the way to get your career started was to become an assistant engineer. Now there aren’t that many opportunities. Where do people get that experience these days?

Trawick: They watch Pensado’s Place. [Laughs]

Pensado: My assistants all tell me that what they learned the most, what was most important towards their career advancement was sitting with me for two years and learning what a great mix sounds like. If you don’t know what a great mix should sound like, you can’t execute that process. So there are substitutes for that process. And not all assistants become successful. In fact, a very small percentage of assistants do. The thing that the studio system does the best is teach the studio process, the etiquette. In other words, how to treat clients, how to blend in with the woodwork at times, how to take the pressure off the engineer. It’s a process designed to feed employees to that particular microsystem. It’s really not designed to make you a better engineer.

Why is that?

Pensado: It’s akin to Michelangelo working on the Sistine Chapel. He’s not going to sit there and paint the blue sky, he’s going to let his apprentices paint the blue sky for two months, and then he’ll come in and do the real painting. So it’s a myth that it’s a process that’s necessary for advancement and learning…It’s designed to create employees that help the studio system and help the engineers. So don’t lament the death of the studios, if you want to be successful in audio. You can get a Pro Tools rig, hang out a shingle, work free for your friends, and then you start developing skills that have value, which people are prepared to pay you for. Be prepared to commit five to ten years of your life, and then you can be successful.

In the book, you talk about the 10 Biggest Mixing Mistakes, " and one of them was "A Mix Lacking in Energy and Emotion.” Obviously a lot of that is a function of the song and the performance. You could do a great mix on a shitty song, and it would still be a shitty song — just better sounding.

Pensado: Yeah, if we’re talking about energy. I’m not talking about “New Age” energy, I’m talking about the way the listener responds and reacts to that song. Does it make you cry, does it make you happy, does it make you want to roll the windows down and go 90 MPH down the freeway at midnight — which Herb and I have done before, by the way. [Laughs] So yeah, songs are the foundation upon which we do everything we do in the music business world…The energy and the vibe, that’s what people buy. When you were 12 years old and that song kicked you in the ass, made your hormones feel good, made life worth living, you don’t remember the EQ of the kick drum, you remember what you felt. The biggest part of my responsibility as a mixer is to enhance those elements of the process that can reach out and grab you…Those elements can be there whether it was done by a pro or an amateur, you can certainly bring those out.

Are dynamics one of the elements that help users connect to songs?

Pensado: Yeah, they’re a huge part of it. Basically, I formulated these opinions, playing in every dive, every bar in the Southeast, because people came there to get laid or to get drunk. And I’ve got to make them buy drinks, and I’ve got to make them stay long enough where the club owner can make enough money to hire me back and pay me next week. So I know that dynamics are important. I know how to divide the frequency spectrum…For example, low end can give you credibility and a feeling of power. Really loud, aggressive mid-rangey sounding guitars can give you another feeling. And really pretty cymbal work can give you yet another feeling. But the ratio of the drums to the music can determine whether it’s a jazz song, a hip-hop song, or a pop song. Think in terms of how different frequencies make you feel.

For example?

Pensado: If you emphasize the midrange, it will make you feel like the song is louder. If you scoop out the midrange it will make you feel like the song is softer. In the songs we fell in love with from the '60s, the individual elements were combined in such a way as to create a feeling. Nowadays we have more clarity in our recordings, so we have the ability to manipulate different parts of the process more easily than 40 years ago. So train your mind to think and listen to music and think about what it is about it that’s grabbing you, frequency wise. And then translate that into the concept into how to make that song grab people and get a reaction from them.

A few years back, you were one of the only engineers willing to reveal what plug-ins you used and how you set them. You said it was not the plug-in itself that matters it was how you used it. It seems to me like the quality and capabilities of plug-ins have improved a lot in the last few years, and you can a lot more manipulation of the audio than you could in the past. What’s your feeling about the state of the plug-in world these days. Are you really happy with what’s out there? And what are you using, of late?

Pensado: Well, one of the tenets of the book is that the process isn’t as important as the product. I don’t really worry about that so much, to answer the question. Not just the audio world, but the digital world in general, from photography to film to movies to TV. Just look where TV is now thanks to the digital world. The gap between analog and digital is so non-existent that it’s a non-issue. I think now more than ever, it’s about choices, not about analog and digital or the state of one and the state of the other. It’s about the fact that we’ve got choices, and those choices can be made based on your taste and what you’re trying to execute, as opposed to the process. The process is more irrelevant now, and the creativity of the practitioner is now the thing that’s most important. So hire a mixer based on his taste and his ability to execute that taste. The gear is irrelevant then.

I’m sure you’ve been asked this a million times, but what is the first thing you do when you sit down at the beginning of a mix?

Pensado: The first thing I do is record my first impressions. So I sit down with a pad and a piece of paper and I listen to the rough mix. And I am very careful to write down the things I like, and I’m very careful to write down the things I don’t like. And then I start the physical process of mixing by going as close as I can to duplicating the rough mix. And then I listen to the elements that I’m being given and I figure out how I’m going to preserve the good things and how I’m going to improve the things that aren’t quite as good. At that point in time I’m probably working on a vocal, in some instances. In some instances I may be working on the guitars. I’m trying to get a foundation on which to build. I always find something I like in the song, and that’s where I try to start. I try to start by making sure that gets the most light and attention shined on it, and then once I get that foundation, I’ve got something to lift the weaker moments up to that benchmark.

That makes sense.

Pensado: It’s sort of like a sculpture — well actually it’s not like a sculpture, because I can start completely over in a mix, whereas a sculpture, once you start you’re committed. But you knock off big chunks of marble first, and then at some point you’re polishing the marble, and at some point you’re trying to detail the eyes. It’s a lot like that process, and it changes with every song. A lot of times it’s what captures your imagination at that moment, and that sort of thing.

So typically are you given the Pro Tools session with the rough mix, or do you just completely start over with everything zeroed out and at default settings.

Pensado: Again, ten years ago, I liked my sessions zeroed. Now I actually like starting from where the rough mix was stopped and finished. So in other words, let’s say that you’re at your home, you call up your DAW, whatever that might be, and you hook up a synthesizer, and then the very next thing you do, within minutes is put on a plug-in. Well, that’s called mixing. So you’re mixing from within five minutes of the creation. Mixing and producing are now interwoven into one. My job is to finish the mix part of your production. Ten years ago, my job was to superimpose my mix on your production. But nowadays, to ignore the things you’ve done to get to the point where you give it to me would be criminal. In the rock world, that’s the way it’s always been. In the rock world, tracking is where the art is, and tracking is where the song comes together. In the rock world, a great tracking engineer has done probably a significant percentage of the mixing already for you because the guitars are tracked they way they want them to sound. Whereas, in the pop world, 25–30 years ago, a synthesizer might only have 30 presets. The first DX-7 only had 32 presets. So people were giving me things that were approximations of things they wanted. Now, the tools that the people that give me information or give me the session, they can get any drum sound they want online, they can get any synth sounds. So it’s a different process now, just finishing the production.

What are your favorite compressor and EQ plug-ins at the moment?

Pensado: That changes daily. I pretty much have everything. I’ve got 40 years worth of analog gear collected — I’ve got a pretty good analog collection— then I’m blessed that a lot of plug-in manufacturers care about my opinions, so I’ve got all the plug-ins. And it’s gotten to a point where I use something different every time. I’ve got so many decisions to make. I will say this: the big dogs, and everyone knows who they are in the plug-in world, are all making excellent stuff. It’s so hard to choose now, even for something as simple as an emulation of an SSL bus compressor. There are so many that sound good. And a footnote to the reader: Just because a compressor doesn’t look like what it’s supposed to emulate in the analog world, doesn’t mean it’s not a good compressor. There are plenty of plug-ins that don’t look like the original. And by the way, that’s a good thing, because it saves you the money that the plug-in manufacturer probably had to pay to license that look. Go by what it sounds like and trust your ears.

So what do you think people will get from the book?

Pensado: One of the many things about the book that Herb and I did that I’m so proud of is a really subtle element that gives you a reason to read it is that if you don’t have life experiences, creativity is a hard thing to have. Herb is gifted at what he does because of a series of events in his life from high school, from college and then struggling in the trenches with some of the great record company people. And all of those experiences gave him the creativity to put together a show that people want to watch. In my world, my life experiences gave me the tools to know what a good mix should sound like, and the energy and all that. Everyone’s past is different, but the book will show you how we utilized all those experiences to become successful in our respective professions, and I think that’s something — and we’ve been discussing elements of that — the process. The book will give you hints into how we used our life experiences to take those processes and make them do the things we want to do to make the end user, in this case an audience, have a good experience.

So you think the book is kind of inspirational, in a way, in terms of how people approach their careers?

Trawick: My answer for that, just gauging on how people have received it, is yes, they seem to find that. We have a lot of personal stories about the show, such as where someone was on the verge of committing suicide and used something from the show to not do that. We’ve had post-traumatic stress folks we’ve helped, and sight-disabled people. We’ve given away about $150,000 in education scholarships, just this year alone. People have used the show as inspiration. We’re really proud about that. Nothing’s greater than when people say, “You’ve helped me so much.” that in and of itself is such a reward for us. It’s a great honor and a great responsibility.

Just scrolling down at the Pensadosplace.tv site, and seeing all the interviews and all the tech stuff, it’s impressive.

Trawick: We’re glad and really, really appreciative that it has resonated with people. But we also work our asses off…We’ve shot 191 straight episodes of Pensado’s Place without missing one. I’m sure that people don’t necessarily know what that requires, and that’s ok, but we do see that they appreciate it.

Wow, 191 consecutive episodes, that’s a long time without a break.

Trawick: And that’s why we’re so tired. [Laughs]