There's nothing like the sound of real reverb, such as what you hear in a cathedral or symphonic hall. That's because reverb is made up of a virtually infinite number of waves bouncing around within a space, with ever-changing decay times and frequency responses. For a digital reverb to synthesize this level of complexity is a daunting task, but the quality and realism of digital reverb continues to improve.

Today’s reverbs come in two flavors: Convolution and synthetic. A convolution reverb is sort of like the reverb equivalent of a sampling keyboard, as it’s based on capturing a sonic “fingerprint” of a space (called an impulse), and applying that fingerprint to a sound. Convolution reverbs are excellent at re-creating the sound of a specific acoustical space.

Synthetic reverbs model a space via reverberation algorithms. These algorithms basically set up “what if” situations: what would a reverb tail sound like if it was in a certain type of room of a certain size, with a certain percentage of reflective surfaces, and so on. You can change the reverb sound merely by plugging in some different numbers—for example, by deciding the room is 50 feet square instead of 200 feet square.

Even though digital synthetic reverbs don’t sound exactly like an acoustic space, they do offer some powerful advantages. First, an acoustic space has one “preset”; a digital reverb offers several. Second, digital reverb is highly customizable. Not only can you use this ability to create a more realistic ambience, you can create some unrealistic—but provocative—ambiences as well.

However, the only way to unlock the true power of digital reverb is to understand how its parameters affect the sound. Sure, you can just call up a preset and hope for the best. But if you want world-class reverb, you need to tweak it for the best possible match to the source material. By the way, although we’ll concentrate on the parameters found in synthetic reverbs, many convolution reverbs have similar parameters.

Reverb Parameters

The reverb effect has two main elements:

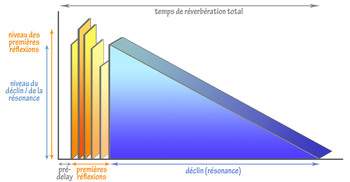

- The early reflections (also called initial reflections) consist of the first group of echoes that occur when sound waves hit walls, ceilings, etc. (The time before these sound waves actually hit anything is called pre-delay.) These reflections tend to be more defined and sound more like “echo” than “reverb.”

- The decay, which is the sound created by these waves as they continue to bounce around a space. This “wash” of sound is what most people associate with reverb.

Following are the types of parameters you’ll find on higher-end reverbs. Lower-cost models will likely have a subset of these.

Room size. This affects whether the paths the waves take while bouncing around in the virtual room are long or short. If the reverb sound has flutter (a periodic warbling effect that sounds very unrealistic), vary this parameter in conjunction with decay time (described next) for a smoother sound.

Decay time. This determines how long it takes for the reflections to run out of energy. Remember that long reverb times may sound impressive on instruments when soloed, but rarely work in an ensemble context (unless the arrangement is very sparse).

Decay time and room size tend to have certain “magic” settings that work well together. Preset reverbs lock in these settings so you can’t make a mistake. For example, it can sound “wrong” to have a large room size and short decay time, or vice-versa. Having said that, though, sometimes those “wrong” settings can produce some cool effects, particularly with synthetic music where the goal isn’t necessarily to create the most realistic sound.

Damping. If sounds bounce around in a hall with hard surfaces, the reverb’s decay tails will be bright and more defined. With softer surfaces (e.g., wood instead of concrete, or a hall packed with people), the reverb tails will lose high frequencies as they bounce around, producing a warmer sound with less “edge.” A processor has a tougher time making accurate calculations for high frequency sounds, so if your reverb produces an artificial-sounding high end, just concede that fact and introduce some damping to create a warmer sound.

High and low frequency attenuation. These parameters restrict the frequencies going into the reverb. If your reverb sounds metallic, try reducing the highs starting at 4—8kHz. Remember, many of the great-sounding plate reverbs didn’t have much response over 5kHz, so don’t fret too much about a reverb that can’t do great high frequency sizzle.

Having too many lows going through the reverb can produce a muddy, indistinct sound that takes focus away from the kick and bass. Try attenuating from 100—200Hz on down for a tighter low end.

Early reflections diffusion (sometimes just called diffusion). This is one of the most critical reverb controls for creating an effect that properly matches the source material. Increasing diffusion pushes the early reflections closer together, which thickens the sound. Reducing diffusion produces a sound that tends more toward individual echoes. For percussive instruments, you generally want lots of diffusion to avoid the “marbles bouncing on a steel plate” effect caused by too many discrete echoes. However, for vocals and other sustained sounds, reduced diffusion can give a beautiful reverberant effect that doesn’t overpower the source. With too much diffusion, the voice may lose clarity.

Note that there may be a second diffusion control for the reverb decay. With less versatile reverbs, both diffusion parameters may be combined into a single control.

Early reflections pre-delay. It takes a few milliseconds before sounds hit the room surfaces and start to produce reflections. This parameter, usually variable from 0 to 100ms or so, simulates this effect. Increase the parameter’s duration to give the feeling of a bigger space; for example, if you’ve dialed in a large room size, you’ll probably want to employ a reasonable amount of pre-delay.

Reverb density. Lower densities give more space between the reverb’s first reflections and subsequent reflections. Higher densities place these closer together. Generally, as with diffusion, I prefer higher densities on percussive content, and lower densities for vocals and sustained sounds.

Early reflections level. This sets the early reflections level compared to the overall reverb decay. The object here is to balance them so that the early reflections are neither obvious, discrete echoes, nor masked by the decay. Lowering the early reflections level also places the listener further back in the room, and more toward the middle.

High frequency decay and low frequency decay. Some reverbs have separate decay times for high and low frequencies. These frequencies may be fixed, or there may be an additional crossover parameter that sets the dividing line between the lows and highs.

These controls have a huge effect on the overall reverb character. Increasing the low frequency decay creates a bigger, more “massive” sound. Increasing high frequency decay gives a more “ethereal” type of effect. An extended high frequency decay, which is generally not found in nature, can sound great on vocals as it adds more reverb to sibilants and fricatives, while minimizing reverb on plosives and lower vocal ranges. This avoids a “muddy” reverberant effect, and doesn’t compete with the vocals.

One Reverb or Many?

I tend not to use a lot of reverb, and when I do, it’s to simulate an acoustic space. Although some producers like putting different reverbs on different tracks, I prefer to insert reverb in an aux bus, and use different send amounts to place the sound source in the reverberant space (more send places the sound further back; less send places it more up front). For this type of “program material” application, I’ll use fairly high diffusion coupled with a decent amount of high frequency damping.

The only exceptions to this are when I want an “effect” on drums, like gated reverb, or need a separate reverb for the voice. Voices often benefit from a bright, plate-like effect with less diffusion and damping. In general I’ll send some vocal into the room reverb and some into the “plate, ” then balance the two so that the vocal reverb blends well with the room sound.

Reality Check

The most difficult task for a digital reverb is to create realistic first reflections. If you have a nearby space with hard surfaces like a tile bathroom, basement with hard concrete surfaces, or even just a room with a tiled floor, place a speaker in the room and feed it with an aux bus output. Then add a mic in the space to pick up the reflections. Blend in the real first reflections with the decay from a digital reverb, and the result often sounds a lot more like a real reverb chamber.

Double Your Reverb Pleasure

I’ve yet to find a way to make a bad reverb plug-in sound good, but you can make a good reverb plug-in sound even better: “Double up” two instances of reverb (each on their own aux bus), set the parameters slightly differently to create a more “surrounding” stereo image instead of a point source, then pan one reverb somewhat more to the left and the other more to the right. You can even do this with two different reverbs. The difference may be subtle, but it can definitely improve the sound.

Originally published on Harmony Central. Reprinted with permission.