You may have heard Richard Devine’s distinctive electronic compositions, or seen his name on patch collections in various synths, but most likely when you hear his work it’s a system sound in a computer program, app, or hardware device, or a sound for a TV commercial. We caught up with him to ask about his work, his gear, and his techniques.

How long have you been a commercial sound designer?

I’d say for the past 12 or 13 years I’ve been working as a sound designer for lots of advertising agencies and video game companies. It’s funny, the audio stuff, the presets and stuff, are the things I do in between my bigger paid jobs. Those projects are more like a labor of love for me. I always learn new things from hearing other people’s work, how they approach making patches and sounds, and as a sound designer, I think that’s just invaluable to me. I try to take the spare time between projects to get myself involved with learning new technology as it keeps your skills and sounds up to date.

What are the typical types of jobs that you get, and what are you usually tasked with doing for your commercial sound design work?

It’s all over the place. It could be designing system sounds for LG television sets, to making system notification alert sounds for the Nook tablets. I worked with Barnes & Noble, and created all their startup animation sounds, out of the box sounds, anything where you connect the Nook to the computer, or to a power supply where you hear the battery indicator sound come on —I did all those sounds. I get paid a lot to do a lot of actual blips and bloops believe it or not.

We all take those things for granted but someone has to come up with them.

Boring as those sounds can be, it can take months sometimes to come up with those sounds that users use on a daily basis. I get hired to do a lot of that kind of stuff, not only hardware integrated devices but also software. The last job I did for a company called Fuze. They are another video conferencing app like Skype, and I did all their log in and call-waiting sounds. In the end it was about 15 sounds, and a couple of short musical tracks that completed the application content.

How long do you usually have for turnaround time on these things? Is it usually pretty fast, or do you have enough time to really experiment?

It depends. It depends on the client and where they’re at in the project. Sometimes they hit me up right at the end where they’ve tried every option, and every option didn’t work, and they’re coming to me, and they need to get it today.

Talk more about the process for these sound design gigs.

Absolutely. There’s a lot of back-and-forth testing that we have to do, a lot of speaker calibration, and also in my job, I also have to mimic the speakers of the device. So they often have to send me the actual device, I have to play the sounds through the device and make sure that within that limited frequency range, that the speakers are capable of playing those sounds. I’m tailoring those sounds to optimally be played in noisy environments, and to be able to sort of cut through the ambience. That will affect the scope of what instruments I’ll use, what synthesis methods. I create the sound sets based on those hardware limitations and make sure that I’m ensuring the best sound quality that I can get out of that device.

So, are most of the sounds that you create made of a combination of different instruments together, or do you use found sounds as a basis, or is it all varied?

It’s all varied. A lot of it is just synthesis I’ll generate in the computer. Some of it’s indeed foley sounds, and sounds that I’ll record like keys, or little launch mechanisms for click sounds. I do a lot of field recording.

What do you use to field record with?

I have a Sound Devices 744T with a Sound Devices Mix Pre-D, the new one. And then I have the 702T, another Sound Devices unit, and I’ll link them up for shoots if it’s a really big shoot. I do a lot of TV commercial work as well, so sometimes we go out and record cars, depending on if I’m working for a car company or what not, so I’ll go out and get six to eight channels, and try to get as many audio perspectives as possible. Sound Devices is great. I’ve taken them out in very challenging shoots, in horrible weather, and even dropped one in a river one time in Florida recording manatees.

Have you done film sound design stuff as well?

The first film I worked on was for James Hughes, a film called New Port South, where I did recording and music for one of the characters in the film, and then from there I collaborated on a film with Brian Transeau — BT. He’s a good friend of mine for many years. We worked on this movie called Look, which was directed by Adam Rifkin, who did Detroit Rock City and a bunch of films. We approached the soundtrack to that film from a completely different angle. We did the whole score with mostly foley stuff, like recording printers and scanners to be rhythm sections, and the humming of refrigerators to be the drones. We were like, “Hey, we’re not going to use these typical symphonic based Kontakt libraries to do this film, why don’t we do something very organic using only found sounds.”

So you we’re doing more than just the sound design, you were doing the music as well on that project.

You could say that it was like a musical sound-design-based score. It wasn’t like your typical score. There were little elements of acoustic instruments, but we mixed them quite a bit with a lot of weird found foley object stuff that we thought would be cool.

What are the main synths you use these days?

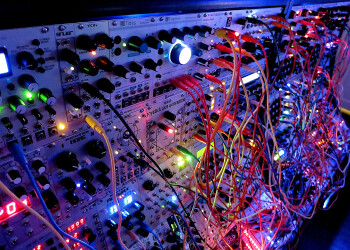

Well, I’ve been getting back into analog modular stuff quite heavily. I’ve been slowly going back into it over the past seven or eight years, and it’s been a lot of fun. I’ve built a couple big systems here at the studio that I’m using to work on design projects and stuff. I have a wide selection of stuff, which is half digital and half analog. I also still have some of my old classics, like an TR-808, ARP 2600. I think some favorites, well I love the Nord Modular G2, that’s a favorite of mine, the Roland Jupiter 6, and I’m a big [Symbolic Sound] Kyma user, I use the Pacarana system a lot for a lot of design projects, sound design stuff, and on my own personal music compositions as well.

|

Audio Mulch is one of the many soft synths Devine uses. This screenshot is from one of his projects.

|

What about software synths?

Software synths, I’m all over the place. I love everything from Aalto from Madrona Labs, to Camel Audio Alchemy. I love the Spectrasonics, Omnisphere, that’s great. I use [Native Instruments] Reaktor, MaxMSP from Cycling 74, Max for Live. I use a lot of stuff from their library for processing. I use so much on the computer, I love Audio Mulch, Metasynth, Supercollider, I still use Plogue’s Bidulel and Photosounder. I like a lot of weird stuff. Stuff that will generate interesting textures, or that processes sound in an interesting way. I also like modular environments where I can start out with basically a blank screen, either take a sound and run it through various processes and then record that output. Or I can just set up a certain environment to do certain things, regenerative, or to give me certain things where I can just record and grab bits and pieces of really cool stuff.

I heard that you recently switched over to using some studio gear from Dangerous music, including the Monitor ST.

I discovered the Dangerous Music stuff through a friend who had recommended them, he’s a mastering engineer, and I definitely trust his ears. So he said that if you’re just looking for something that’s going to be great, where you’re not going to be guessing about anything, go with Dangerous. And they’ve got a good reputation. I figured if it was good enough for my friend who does mastering all day long, it’s probably just as good for me.

I know from personal experience that the Dangerous Music gear sounds amazing.

I was very skeptical, I was just like, “Is it really going to be that much difference?”And I was reading all the reviews and comments on Gearslutz and all the reviews online, and I kept seeing the comment: “I’m a believer now!” I was like, “I know, I’m not gonna fall for this hype or whatever, I’ll be the judge of that.” But then I hooked it up and I was like, “Wow. They were not kidding.”

So is Monitor ST the only one, or did you get another Dangerous unit, too?

I just got the 2 Bus LT, a 16-channel audio analog summing box.

The whole analog summing thing is a bit controversial. Clearly, you’re a believer.

I guess it depends on what DAW your using to do your bounce downs. I have a Pro Tools HD rig here and I bounce running Nuendo, I use Logic, I use Ableton sometimes, it just depends what project or client I’m working on. It’s weird because I came from more of an old school background so I used to separate all my mixes out into an analog console — you know, run every output of my drum machine and pan them all. But then when I started mixing inside the box using the computer, I noticed the way that things got bounced down they sounded a little flat to me. So what I used to do was just record what I called an “everything open” mix. I would have one computer do playback, I would separate all my instruments out into a mixing console, and then record everything completely open into the other computer.

I noticed that it opened up the separation between the instruments more; there was also a bigger perception of depth between the sounds, more clarity less digital mushiness. It made a world a difference for my music at least. I mean, it may not work for everybody. My stuff gets kind of crazy and complicated, there’s a lot of like, super macro, sort of needlepoint textural stuff happening all the time. So for my stuff it was better to separate everything out physically to get the sounds to kind of feel like they came apart from each other a little bit, and instead of it being kind of two-dimensional flat. When I was doing in-the-box bounces, things just didn’t get that nice spatial depth, that stereo image that I noticed. I noticed it a lot with my music, with other forms of music it was a little more difficult for me to tell. Like if I were to do a hip-hop R&B track or something that had more simple instrumentation I could hardly tell the difference on stuff like that, but for more complicated pieces of music I tend to fill up the whole frequency spectrum pretty quickly.

Your stuff’s very textural.

Exactly. So that stuff is where I noticed it more.

Because there was so much going on, it gave everything a little more of its own space in the mix?

Exactly. I think it all depends on what kind of stuff you’re mixing. When I was doing more simplified mixes, it was harder for me to tell the difference, but the more complicated the sessions were where I was running 50–60 tracks, and I was summing things — summing down bounces to try them out — I definitely noticed the difference.

Tell us about some of your other studio gear.

I’m using the UAD Apollo 16 card for my mixdowns with the UAD-2 stuff that I love. That’s another thing I can’t live without, my UAD-2 plugins.

Are there particular ones that you really like of their plugins, ones that are like go-to for you?

Of course I use the Pultec, the Fairchild Tube Limiter collection, the Cambridge EQ, the Neve channel strip I think is the 1073 Preamp & EQ, I love that, I use the Precision Limiter, the Precision Multiband Compressor. I mean, I’ve got the quad processor and two UAD cards in my Mac tower back here, and you know, my sessions are pretty much scattered with UAD plugins. I love their stuff. Even though people probably wouldn’t know the difference because my stuff is so crazy and all over the place, but I just love some of the things you can do as far as saturation, and shaping the sounds that fit in like a puzzle in a big mix. They really can do some cool stuff. I like the McDSP stuff as well, and a combination of that, plus Waves, and I use some outboard — basically what I’m doing for my mixes now is I’m summing through the Dangerous 2-Bus, with the Apollo 16, and then I’m taking my stereo mix out to an Avalon 747SP and then running that back to the Apollo on my left and right mix, to give that kind of nice warm glue.

The Avalon, that’s a compressor?

Yes, it’s a stereo mastering compressor that has also a really nice EQ section, really transparent. Something about the sound quality of it for me helps warm up the sterile, very cold digital atmospheres and space I like to create, so I’m trying to bring a little more of the warmth back into the mix to make it more pleasant to listen to for longer periods of time.

Do you ever feel like you have too many possibilities in terms of all the sonic tools available?

There is a lot of stuff, a lot more than there was ten years ago. Back then, if you were getting into making electronic music or music with this type of technology, you had limited options, and things were very expensive on the hardware side. But now, you can do almost everything with software, and can get almost any emulation, or get 90% close to what the real thing is. I think having too many options isn’t necessarily a good thing always. I’m one of those people that if I’m presented with too much stuff, I don’t often make a decision at all. I sit there for minutes, looking at everything going, “Well I could use this, I could use that, ” and I’m not really tackling the problem of accomplishing what I was supposed to do — recording a piece of music, or creating something. I’m being distracted by how many tools I have, and not really doing anything with them, and I feel that I work better when I limit myself to just using a couple things that I know really well. I come up with much better results like that than trying to use everything that I have.

|

|