Producer, musician, artist, painter… Our guest today is someone who has always been looking for a way to let Art be expressed in every piece of music he has worked on. Primarily known and renown for heavy records and powerful bands, his aesthetic vision is and has always been far more subtle and refined than his resume could indicate. Actually he started his musical journey in the early '80s with Herbie Hancock, leading him to a long path filled with successes.

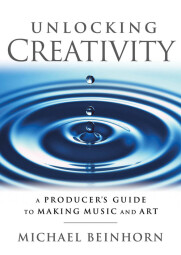

As genuine as every project he’s produced, he started collecting thoughts and ideas about his methods and production processes and naturally in 2015 he came up with his own book — the first of its kind — about the creation and recording philosophy: Unlocking Creativity (Hal Leonard, 2014).

I’m very pleased to share with you this fascinating conversation I had the extreme honor to have with the no less amazing Michael Beinhorn.

Hi Michael, it’s a great honor to have you here! Before we start the interview, in the past few days I’ve read some interesting things on your blog about the recent loss of two icons in the music industry, David Bowie and Lemmy Kilmister

[ed note: this interview took place prior to Prince’s death]. You’ve posted a lot about it. So first question: How do you feel about it today? What about the things it has left for people like us, in the music industry?

Well, you know, the loss is devastating. It’s tragic. There is so much significance to it though, because they are not just like isolated people dropping off, it’s kind of happening one after another, like dominos falling…To me, and I guess to anyone who looks for a certain significance to that happening, it feels like there is a pattern to it, that something is happening…You know, it’s like “Who is going? How they’re going? When they’re going?” Like the first two half weeks of 2016 we’ve lost about 9 or 10 people, incredibly significant in the arts, especially in popular culture. This is, to me, a lot of things. I mean, the tragedy aside — everyone is experiencing this — like what happened with Bowie was a main shock, but it was underscored even more by the way he went out and the record that he released. The song comes out like, a few weeks before he dies, and everyone’s like “Oh, a new Bowie record!” Then all of a sudden he’s gone and people are sort of reflecting on this. They turn around and listen to the song again and kind of say “Oh sh***!” It takes an all different signification, shocks to a lot of people!

Him going as quickly as he did without any publicity was a big shock. Because he was a massive cultural icon. I think history has moved away from him so much that people weren’t really thinking, before he died, about what kind of prominence he had in the world and how much the world has changed because of his influence. But, with all that happening at once, people just came back to him and they started to realizing. I don’t think a lot of people are even aware of how they feel, because people were experiencing it virtually and not analytically. There’s just this tremendous amount of loss they can’t explain but he influenced our culture; our culture wouldn’t exist as it is, in the shape that it’s in, without him. Interestingly enough — although one could say someone has been more influential musically — I think he may be the most influential popular cultural figure who has passed away in recent times since…I don’t know…possibly since John Lennon! Because of the cumulative of impact that he had, that he didn’t just affect people artistically, he affected the world culturally.

On many levels!

On many many levels, yeah. He basically spoke for all the freaks in the world, people who just talked different and who couldn’t really explain themselves, who were afraid of…I think he made it easier for gay people to be who they are in public and express that, you know, among certain other things. He brought a lot of things to light, that were buried in the mass unconsciousness. People were afraid, ashamed of being themselves or being able to expose. He made a lot for a lot of people.

And also independence for the artist, in a certain way.

Yeah, he was doing things the way he wanted do. One of the things that I editorialized about was the fact that, when people are going like: “Oh, Bowie’s gone, what a shame, you know, I’m all broken-up.” A lot of people are talking about all the great rock records he did, you know. Actually some people are talking about the stuff he did after but — and I wrote about this — no one had said anything about the fact that, when he went from Diamond Dogs to Young Americans, people got so upset that he lost a lot of fans! People accused him of pandering to black music, it was very very racist. He was hated for it, he was vilified. And he just went on and inspired a lot of people…I’m sure people in his record company were like: ”What are you doing?” I mean kind of like when Bob Dylan did when he went electric after being an acoustic artist! When he performed at Newport like in ’66 and then people were throwing things and saying how he was a great big sell-out!

That was a sort of revolution back then! (Laughs)

Yeah! I mean, the thing is…This is what an artist does! Sure, you might take some advice from somebody, at some point, listen to what they have to say but, at the end of the day, your art is based on how you feel. It’s based on your intuition and you’ve got to roll with that. You got to take your chances and if the choice that you make, based on that, appears to be that you screwed up, you have to live with that.

You have to live with your decisions.

Yeah!…The consequences are irrelevant…That’s what makes you a great artist. And if you screw up, you screw up, but that’s not even an issue. You have to move forward, and you have to trust your instincts. People nowadays don’t think like that, and certainly not in the arts. It’s about short-term gain, the fastest way to get very widespread success and do something that’s familiar, that sounds familiar to other people, to conform.

Well, everything leads to the first question I wanted to ask you. How did YOU start? Talking about mentorship earlier, did you have one?

I didn’t start with a mentor. Actually I just grew up in a house where music was constantly being played, and my mum played the piano. Everyone loved music and I just fell into it, it was just something that appealed to me. I guess I had a calling for it and everything extrapolated from there. I met people who were mentors, you know. I don’t think the term was used back then and you didn’t necessarily look for that kind of thing, it just sort of happened to you. Now there’s much more of a conscious pursuit of trying to find someone who can mentor you but I ran into people along the way who provided with insight thoughts, technical skills, knowledge, or just watching them work, just watching how they did stuff and just being absolutely dazzled by their brilliance. It wasn’t a studied road; it was something that kind of fell together and in many ways I was incredibly fortunate or star-crossed, depending on how you wanna look at it! (Laughs)

So you started with the band Material, playing with Bill Laswell and then, in 1983, you worked with Herbie Hancock, on Future Shock and the song Rockit. It’s still considered as a pioneering masterpiece. How did that happen? Did you think you were creating something special at the time?

Yeah. Certainly none of us had any way to gauge what kind of impact it was going to have but you know, we knew we were doing something that was amazing…I think, sometimes when you’re making something that’s gonna be fantastic, the whole time that you’re doing it, you just feel like you’re being buoyed or lifted by something else. There’s a real sense of excitement, positivity and euphoria, and it just carries you along and inspires you. I mean that’s not always there but, when it is, and when it keeps happening, every time you go to the studio to work on that particular piece of music, you just know you’re in the right place. Everything, every subsequent layer that we added, it just fleshed out this piece of music and made it more and more amazing. Everyone was happy and it felt good.

Then you worked with the Red Hot Chili Peppers, and you worked on great rock albums like Superunknown, Celebrity Skin… How do you make the transition between working with Herbie Hancock and such artists? How did that happen?

Hmm… I don’t know!! (Laughs) It felt like a logical progression to me! A lot of the music that we worked on in Material was…None of it was rock, it was either jazz influenced or RnB influenced or, later, hiphop influenced. There’s a connection with all that music and a lot of it has to do with the group. I mean rock music is also derived from R&B and from african music so it all kind of followed the same kind of path. For me it didn’t feel like a change or something weird, I like the different tonal colorations of rock music and it was fun to experiment with distorted guitar tones and to work with bands that played guitars primarily instead of keyboards!

It gives another energy.

It’s a whole different thing! But it’s still tonal colorations, it’s still working with a group, it’s still trying to construct a song arrangement that flows properly…The end result is supposed to be something that feels good to you. When you listen to it, there are no points where you feel this connect happening.

So you’ve done all these albums and then I read that you were hired as a VP of A&R at Atlantic Records. What was this position compared to the freelance job of being a producer? Was it a good experience?

Well… Not really! (Laughs) For one thing it was kind of like a “puppet” position, it wasn’t real, like I didn’t have the power to sign an artist. I kind of got involved with Atlantic because I thought that I could make a difference and help them more with artist development, which is something that I thought they and every other record company were really lacking. That they didn’t have like old school development; they really were looking at artists as being kind of fully-formed and kind of like: “Ok, whatever they do, we’ll just exploit that and make a record with that!” Instead of looking at an artist and going like “Ok, this is something that has potential, how can we get the potential out of the artist?!” I thought that they were lacking that; I still feel all the major record labels are lacking that. They don’t make records like that anymore though… so it’s kind of a non-issue for them. But that was my initial impetus for going to Atlantic. I actually turned down a much higher-paying job at a different record company to do that because I thought that there was a real potential to do something valuable and what they really wanted me there for was to kind of attract artists, to attract rock artists I think and just kind of like trap me out and say: “Oh you know, we got this guy working with us!” And the relationship was…without any kind of merit at all. Their A&R departments were very segmented, very fractious, they didn’t really kind of interact with each other well, they were very competitive with one another and it wasn’t a great environment.

But still an experience though…

Yeah! I mean I’m not gonna say that if I had to do all over again I would change it, you know. Because it’s all led me to this point and that’s great!

Let’s talk about your production methods and process. Say I’m in a band and I would like to work with you. How do you start working with the band?

The start point of a project is really analyzing the music that I’m gonna be working with, getting into it and having an understanding of what I’m gonna be working on. To be able to dissect it, to analyze it, to see where it isn’t working: that’s more important to me than figuring out what is working. If I agree to work with the artist, I’ve already made the determination that something in there is functional. The real key is to figure out what’s not functional and how to make it (what’s not working) become functional but also do it in a way that’s gonna appear organic to the artist music; to not add like parts and thing like that — or arrangement ideas — that are going to sound far. It all has to fit, it all has to work together as a whole. In a lot of cases, you can have a piece of music that has a whole bunch of great parts but doesn’t work because those parts — once they got stuck together — something happened all of the sudden. There’s no coherency anymore and what sounded like a great part on its own, sounds like crap in context with a different part. So all that has to get analyzed, melodies, harmonies…

So you like to spend some time with the band, going to the rehearsals, going to see them live…

I like to, if I can! Otherwise I work with what I’ve got, in terms of demos, and I figure out where I feel there is disconnects happening and I start from there. I just begin implementing changes, working with the artist, seeing what they wanna do. Obviously I need to get into their heads as well, and see what their process is, how they’re looking at what they’re doing, making sure that whatever conception of the recording is has to be something that everyone can agree with. Like, if I get an idea in my head about what this is gonna turn into, I wanna make sure that this is not gonna be something that the artist is later gonna turn around and say: "What is this? I don’t recognize this!"

So you make sure that the concept of the album is 100% assumed by every member of the band.

Well, as close as possible! I’ve done that too, and later on the artist would come back and say: "What is this?!" So, at least, if I have a foundation that I’m working from that is familiar, then I can say: “This is exactly what we discussed in the beginning. Do you not remember?” And going through it step by step, because a lot of times artists can get sidetracked or lose their concentration on what they’re doing and then, somehow, get jogged back into the process and not understand what they’re hearing. It’s very difficult and delicate. So I want to create the best foundation possible on which we’ll build the recording. And then after that comes rehearsal, going into pre-production and making sure the performances are right, making sure the song tempos are where they need to be…

During the production process, what are the things you really care about the most, technically speaking?

Well, generally it is everything! I like it to sound good, I like the performances to be the best performances that the artist has ever done, you know… Ideally, it should be the best of everything, which is a very general and subjective statement to make. At the same time, if you’ve taken the job of being a record producer, you kind of have to get your own sense of what that means to you. So you should be able to deliver that, you should be able to provide that for an artist that you work with. And if you can’t do it, then you’re not really producing a record; you used more your utility function, you’re more of an engineer or something like that. Or like a coach for a basketball team.

Which is not the same!

It’s not the same! There’s a certain amount of coaching that goes into producing a record, there can be a lot of psychology as well but, again, as a producer, my feeling is that you have to be able to get a clear vision about what it is that you’re doing, how you wanna make a recording. It’s important to know some of the technical aspects of the process. To have a clear vision in mind to understand how you wanna realize that.

Are there things you always do in a recording process? For example, like getting the band playing live all the time, double-miking all the instruments…?

Not really. I’m actually trying to move as far away now from anything familiar as possible, because I’m going to get sick of it. I just wanna try different stuff now, things that I haven’t done before, because it gets boring after a while if you just keep using the same tools, the same this, the same that…I love hearing a band perform live or I should say I love the feeling of a band that can play together live. I haven’t worked with one band in my entire life or… nah, maybe one… (laughs) that could actually get that going in a recording studio. Every band I’ve worked with sucked when they played in the studio! Because it’s a whole different vibe! It’s not like the 1950’s, where you had one microphone, you basically set up the way you set up when you’re in a club and played your song. It’s not like that anymore. When people make records with like small amps and stuff like that, if you can get a sound that resembles the sound of the band live, that’s great but more often than not, it’s not gonna happen…Some bands they play together live well, but when you put headphones on them, they listen differently.

Definitely.

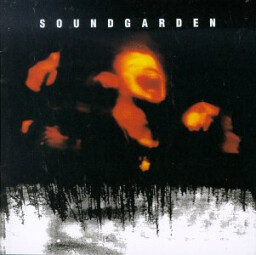

Normally there’s a certain amount of room. It’s hard to take a band that’s primarily a rock band and record them like they’re a blues band playing like in a little club somewhere in the South. It’s not getting the same thing! I have to make the determination where the diminishing returns come and if trying to get that live feel happening is more valuable that trying to get this big explosive sound. And at the end of the day, to me, like having the big powerful sound — where you’re able to give the impression that band are playing together — is highly preferable. It may take a little bit more time, but the end result is always better. [Soundgarden’s] Superunknown, I think, is a good example of that because you don’t listen to it and hear the fact that each instrument was laid down separately. It sounds like a band playing together.

Totally! Great work, bravo!…

Well, hey, thanks! (Laughs) But the thing is that if you know what you’re looking for, you can achieve that without trying to force the situation and following an esthetic that may be completely irrelevant to what it is that you’re trying to do. I mean, I love people who talk about: “Oh, I wanna capture this live feel!” Like, great, do it! if it works for you, good! But are you doing it because you think that this is the best way that this band is being represented or you’re doing it because you’re trying to find some faulty aesthetic that makes you feel like you’re making a vintage-sounding record or something like that? I can’t stand that kind of thing! I mean, as I said, I love live performance but I love synthesizers, I love sequencers, …

I can see that behind you! (There’s a whole great rack full of modular synths.)

Yeah! Well, you know… (Laughs) Those are beautiful modulars and no one has ever been able to make it better! But there are so many tools to make music now and people blame the tools for the shitty music! It’s not the tools that are making the shitty music, it’s the people using the tools that are making the shitty music! If you wanna make great music with the tools, you have to use your brain, and you have to use your heart, you have to take a step back and go: "What am I doing that’s unique with all these tools? Because I’ve got so many of them now!" Instead of being overwhelmed and instead of being like: "Oooooh !" (whining) Or with this one thing I will do this one function and that’s all I need it for. Or saying, I’m making a pop record, which means that I do the drums in one pass, I edit them, I sample/replace everything and call it a day?! You can’t make a record like that! You can use sample replacing for a lot more than just a rogue wave, a rogue method of production, just the same as you can use synthesizers in a rock track, in many more ways than people are using them now. There’s a lot of really cool things!

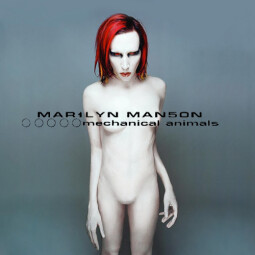

This is something that I really like on Mechanical Animals [Marilyn Manson] for example. There’s a great blend of rock band with synthesizers, there are melodies, high energy with dynamics. What did you do, technically speaking, to achieve that particular sound?

Well, nothing unusual…When you talk about that, I think you may be identifying it as specific technical things but, really, it was just the aesthetic of that record! I envisioned that record as a really unique marriage of electronics and rock music. I kept referring to it as a cyborg, which is like half-man, half-machine. And they had both before — and after — but I never felt that they really achieved that same kind of "blend, ” that there was something really special about our record, tonally, that none of his other records was really able to achieve. Because it was intended to be like that. So when you do things by intent, and have a vision for something, if you intend something to wind up a certain way, you figure out all the tools that you need, to be able to achieve that goal. To me, it was a combination of…it was just certain tonal combinations that work well together! I didn’t do anything really out of the ordinary, but there are really subtle things, like adding certain processing to a guitar or to a bass. The drums are pretty much recorded the way I would record a drum kit.

Like a typical one?

Well, the way I would do it, which means not be typical to someone else! (Laughs)

Can you explain a little bit more? (Laughs)

Well, I like to use a lot of microphones, I like to get a very refined drum sound instead of a very… hum… phew… unrefined drum sound?! (Laughs) I like to cover a lot of ground tonal, I like a lot of presence from the instrument. I like a lot the immediacy, I like the speed. But, to me, if I know that I’m gonna combine a drum kit with guitars, let’s say, and I know that there are certain aspects of the drums that are going to compete with guitars in certain frequency ranges, I have to figure out beforehand how to make the frequency ranges so that the drums sit with the guitars, so the both can coexist without too much biting. For example, cymbals are very very difficult because you can lose them in guitars or they can lose your guitars for you if you haven’t really considered how you’re doing it. So I like to try and make sure that I’m using cymbals that seem to work tonally for me; so cymbal choice is very important. I like to pay attention, as with the hi-hat and the snare drum, to instruments that are going to infiltrate into those frequency ranges, that are part of the drum kit, and tuning drums away from the tonal ranges of other instruments. This is specific to each individual project; that’s what makes the most sense.

For sure! What was the special process that you applied on the guitars and bass on this album particularly? (Mechanical Animals) Do you remember?

I said —and that was true — that there was virtually nothing on some of the guitars. When Twiggy did his guitar tracks, it was mainly like a Les Paul through a Marshall stack and that was about it! Like two or three microphones on the cab or something like that, nothing really special, you know. But the choice of the signal path, the mic preamps, the mics we used, just kind of sit there and balance guitar sounds to each other, make sure the phase is good and… you know, you know where all this is! I mean I think I used a little bit of synth processing on guitars but I don’t remember exactly where or when. I mean, when we did Zim Zum’s guitars, it was a little bit more complicated because he didn’t sound the same as Twiggy so we spent a lot of time trying to construct the guitar a bit. Well, his guitar actually sounded good against Twiggy’s… But, combining all these elements together with the electronics is part of what gives the record its uniqueness, the fact that we were using drum machines on some songs and live drums plus drum machines on some songs, and sequencers and live drums, you know… But again, the tonal aspects of the instruments are designed to sit well with the electronics, to sit well with the electric guitars. It’s not a rogue process, it’s not something where I kind of “did what I do” and threw some mics and ”Oh, there is my drums! There is my this, there is my guitar!, ” you know. It was carefully thought out. No, actually it wasn’t carefully thought out, it was more a matter of sitting there listening to it and going like (pointing his finger): ”that’s right!” For me, knowing instinctively what a particular signal chain is going to do is part of it, so I can decide: “I’m gonna use that microphone going into that microphone preamp and it’s gonna come through here, it’s gonna bus there and it’s gonna look like this, it’s gonna sound like this and that’s how it’s going to tape! ”.

Knowing that, do you have “special” equipment (microphone, mic pre’s, …) that you love, cannot work without and always bring you on a session?

I love the Neve Germanium stuff. I always have loved it; there’s just this dirtiness to it that no other mic pre has. I really like it a lot. The 1057 — the old, early/mid-60s Neves — they have fantastic low-end response, they’re very very thick and punchy. They’re dirtier than the silicon stuff, than the later Neves, but they’re punchier and they seem to be more focused as far as not bleeding into other signals, frequency-wise. The harmonic distortion sounds definite obviously, function of the germanium transistors and also the transformers at the back end, which are just like enormous! They’re really really big! I like the 1058. My 1058s… I don’t remember if they have transformers going out, I think they don’t have those… (thinking) Originally they did, originally they had the same transformers as the 1057 and they’re supposed to sound fundamentally the same. The 1058s have just a different topology because it’s a high and low shelf, fixed, and the mid-band is switchable with boost and cut. The 1057 has got more control to it. The 1058s I have don’t sound good on drums but they sound good on guitar and bass. But I like those a lot; if I’m able to use those, I’m generally pretty happy!

What about microphones then?

Hum… It varies so much. I find like you can’t use the same vocal mic on every singer. I tend to like the ELAM 251 a lot. That’s what would be the best sounding microphone I’ve ever heard, but some people sound terrible on it! It’s just the way it is, the voice is just an unique and unusual instrument, there is no one way to capture it perfectly…There are so many great microphones. There are some microphones that I’ve sworn by, on one project, and then I go to the same microphone on a different project and I think to myself “This sounds horrible!” And it sounds so bad that you can’t believe that this is the microphone you’ve chosen! The Neumann U47 FET sounds really great on a bass drum. I’d say that the U47 FET and the (Shure) SM57 are two microphones that are pretty much gonna get used at some stage in a recording process that I work on; they’re kind of unavoidable! Everything else is really subject to scrutiny. I like Audio-Technica mics an awful lot and I try to use them as much as possible, I just love what they do. It’s not always gonna get me what I want — same with the Royer, like the 122s, great microphone, sometimes there’s something that’s more usable — but it gives something that I like. Like I said, there are so many great microphones in the world!

So it depends…

Well, there’s always something new to try, there’s always something great out there, that you haven’t heard before… A part of what makes it fun is the fact that there are so many different ways to solve the same problem. You may wind up with like 2 or 3 different great ways to get what you want and sometimes making a choice based on something that you’ve never tried before is a lot more fun than using your “tried and true” kind of thing. It just so terrible when this process becomes familiar… As the saying goes: “Familiarity breeds contempt”…

So I assume you don’t like recipes?

I know I do things a certain way and I try them but I’m prepared for them to not working and if they don’t work, I’ll just be like “Ok, what’s plan B?” It’s the easiest thing to do in the world, put an SM57 on a guitar amplifier — everyone does it, people have done it, people continue to do it — it always works. But you know what? That may not be the sound that you’re looking for. And if it’s not that, it may even be a component part of a bigger sound or a different sound. And you have to be prepared to go to a different plan, especially if what you’re hearing in your head is not what you’re hearing through the speakers. And you wanna get what you’re hearing in your head as opposed to saying like ”Ok, it ’s good enough whatever I’m hearing through the speakers."

Well! That leads us to the last part of the interview. I would like to talk about the book you released in the course of last year Unlocking Creativity. First questions — that call for a long answer: Why did you release this book? What did you discover through this process while writing the book?

Ah yeah: why?!! (Laughs) As a matter of fact, I realized that, over time, every book ever been written about the recording processes have not been really creative, that they’ve been mainly technical. My conception of record production is that there is a technical aspect of it but, it’s just far more about it that its creative and involves interpersonal dynamics, some things like that…I realized that no one had ever addressed that, to a great extent. My initial intent was not to write a book though, I just wanted to write down some of the protocols of how I worked, just to kind of preserve them and to see what it would actually look on paper, because I started thinking about this. I was like ‘ Wow! There are so many different approaches that I use when I’m working with artists, wouldn’t be interesting to have that as kind of like a “knowledge base” that existed in one spot and that could be referred back to?’

So I started writing stuff down and within a very short amount of time I had like a large volume of information and it just occurred to me that it was turning into a book. And I wanted to present that to people because I find that music and the evolution of music and the evolution of music technology and recording have been by and large an organic process; that when things evolve organically, there isn’t much thought or philosophy applied. There isn’t much backtracking or looking at the process and thinking “Wow! What was behind this?” And that, in itself, I’ve noticed this very fascinating to people, people wanna know what was behind a certain recording or a familiar piece of work. People wanna know what the construction was. They always ask the same questions: “What mics did you use? What mic preamps did you use? What kind of compression? What kind of desk did you record through? Instead of ”Why did you do it? What was your thought process? What motivated you to make the record sound like this?" Not “How did you make the record sound like this?” but “What motivated you to make the record sound like that?”

And I think now, because there’s a continuum that’s been broken, music has become a lot more removed from its emotional source, which is one of the reasons that people have a problem with it now, more than ever before! I’ve never seen such a disconnect in the music community or a disconnect in people who are music listeners. Part of the reason is that there is this break, and in order to re-establish it, I feel for the first time there has to be a real conscious effort made to understand the process, to really kind of… not necessarily intellectualize it, but to understand how to use your intellectual process to be able to experience it on a novice level; which is a strange concept. But if you open yourself up to it, it actually makes a lot of sense over time. And I feel like this is the only way that we’re going to be able to re-establish that time. Not to keep going back and making records that sound like Neil Young or David Bowie or The Beatles or any of that “crap.” I mean, this is old music for God’s sake! Like, enough! We’ve heard it so many times, it’s a tragedy to see these people going but… they have to die! There has to be new blood now, there have to be people in the world. I think that their deaths are really underscoring this tremendously. I don’t wanna see them go but at the same time, I feel like what we have to be aloof of that whole sense of security that we have and this, taking for granted of artistic talent, artistic freedom and artistic creativity as things that aren’t resources that have no intrinsic value to them, whatsoever. The fact that you can’t put a price on something doesn’t mean that it isn’t priceless! And that’s one of the problems that we’ve been facing, insisting so much editorializing on how useless art is in the contemporary society, especially in the tech community. But you see how people around the world are reacting to David Bowie’s death. That is an indicator right there that this way of thinking is completely idiotic.

This way of thinking is over.

Well, it’s not! It should be over but it’s not! What this is, is a challenge. We can’t just sit here and mourn the deaths of great people, we have to let these deaths inspire us and have to let them help us, to find the mechanisms inside of ourself to help us speak fluently for the rest of the world, to express what we’re trying to say as perfectly as possible.

Alright ! (what could we say after that…!?)

Ok so if I take four albums that you worked on, like Future Shock, Superunknown, Celebrity Skin or Untouchables, why did you make those records sound like they do?

Because I wanted to help the artist to express to the fullest possible degree what they were trying to do on their record. In the case of Herbie Hancock, he was about to get dropped from Sony, from Columbia. This was like his one song essentially. We had no intention of making something that was gonna give him a big hit you know, that was purely circumstance. Serendipity. But we wanted to make an artistic statement. He just kind of went along — kicking and the screaming basically! (Laughs)

“Music has become a lot more removed from its emotional source, which is one of the reasons that people have a problem with it now.”

As far as Superunknown…everyone knew that their next record was going to be huge. But I knew that if we didn’t do everything possible to make sure that their next record was amazing, that it would be sort of like dropping little pebble in an ocean, instead of someone dropping a comet, an asteroid into the ocean and devastating all mankind!! (Laughs) I did something on that level. I just wanted to make sure that it was the most powerful statement. I mean, I think that’s really the one unified element in all these things. I’m trying to look for the artist’s weakest points and trying to eradicate them, and looking for the strongest points, and trying to strengthen them to the greatest possible extent. That’s the one thread to everything that I have done: just looking, searching for a vision and searching for ways to be able to amplify the artist’s strengths.

Ok! My last question will be focused on education. What kind of advice would you give to any young engineer or producer, or anyone aspiring to become engineer and/or producer?

Find your voice. Become who you’re supposed to be. Trust yourself, do what you need to do to be able to survive but find your voice. Learn everything you can about what it is that you do. If you’re involved in recording music, learn to be a musician, understand all the aspects of that. Learn how to be a step ahead of everyone you’re working with and have a musical sense, be able to listen to your own intuition, be able to use your emotions as tools, to analyze music instead of using to use your intellect to analyze music, which will get you exactly nowhere. If you copy someone, make sure that you do it for the right reasons. And if you gonna copy someone, be the best imitator that you can possibly be! (Laughs) Imitation can tend to innovation into the right hands!

Thanks! Another great sentence to quote! (Laughs)

Well, I don’t know… !! (Laughs)

A LA BERNARD PIVOT — THE 5-QUESTIONS PART

What’s your favorite memory about producing an album? (music-wise, human-wise…)

Pfff… Can’t answer that! It’s impossible! There have been so many…

If you just have ONE moment or memory that comes back to your mind…?

Ok, the one that pops to mind is I’m on the isle of Capri, you know, off the coast of Italy, working with Aerosmith at Capri Digital Studios – which is one of the most beautiful places on the face of the earth – and I’m looking, I look over to my right-hand side, Joe Perry’s standing there, with a shirt off (Laughs), playing a guitar solo…There’s a window and through the window you can see the entire island and beyond that the Mediterranean sea. And at that moment, I just was like “Ok, it can’t possibly get any better than that!” (Laughs) It didn’t really have to do with the fact that the music that we were working on was anything spectacular, it was just like “Oh my God, here I am and how did I get there, how did I end up in this place? This is fantastic!” It was just a very very inspirational wonderful moment, I loved that!

Well, I can imagine… What’s your worst? Or maybe the most difficult situation while producing an album ?

There have been a lot too, really! The hardest ones are generally when I had to go to a performer on a project and say “You’re not cutting this.” That’s one of the most painful thing. It’s just… devastating because I know that I’m going to be hurting someone’s feelings very badly, and probably breaking their heart, but at the same time my mission is to make their project be as good as it can possibly be. So I have to really choose between someone else’s feelings and allowing a record to become mediocre, based on the fact that I didn’t want to wound them in some way. At the end of the day, the choice is always to take the road that makes the recording the best it can be, because that’s what’s gonna be left behind. People’s feelings are gonna get mended over time, they’ll find ways to survive, but the recording is never gonna be fixed, and if you just kind of put all that in the back burden, going like "Oh I’m afraid of confrontation, I don’t wanna hurt people’s feelings, I’ll try and make it work, ” that’s baffling.

Which artist would you like to work with and why?

Phew… Hahaha! (Laughs)… I’ve never chosen projects that way so I can’t really answer the question… I don’t know, Jimi Hendrix! ‘Cause he’s great! I tend to work with people based on…They kind of either wind up in my radar and there’s something about the potential relationship that just clicks. I can’t really explain it beyond that. There are so many talented people out there, you know…

And somebody still alive? Somebody you’ve heard on the radio, or see him/her live, and you would like to work with…?

I’m left blank sorry!

You’re hired to work on a project on a desert island. You need to pick 5 tools, pieces of equipment to work on this project. What do you take and why?

Wait a minute, does this mean that there no recording facility on this desert island, apart from what I bring? Or this means there’s already something that exists there…?

No, there is already some equipment there… (Laughs) But you need to take 5 pieces of equipment with you.

Aaah, it depends on what kind of equipment they have!

Very good answer!

I always have very good answers, ha ha ! (Laughs) That depends on them, I’m not gonna go to any desert island’s studio that’s got like a crappy console in it haha! (Laughs) Send me to a different desert island then, that’s got a proper recording studio in it! (Laughs)

Ok I’m done, you got me!

Well… you asked for it! (Laughs)

Final question though: do you have any leitmotiv or quote about music that you like to use?

I don’t know… Things are constantly evolving… And should constantly be evolving. I cannot produce quotes on command! (Laughs) Come on, haha! And I think I’ve already given you a couple anyway!

Yeah, definitely! Thank you very much for this interview Michael!

Thank you, too!