As a newcomer in the virtual acoustic pianos family, VI Labs declares its ambition right from start, and it begins with the name: True Keys. Does it hold its promises?

Developers have made enormous progress in recreating, by means of sampling (or modelling), what many call the king of instruments: the acoustic piano. Without going over the whole history (you can refer to the different reviews published on Audiofanzine), it all started a long time ago with somewhat rudimentary tools, we then lived moments of grace with several hardware units (especially with the Kurzweil pianos like the K250 which, as the legend goes, even managed to cheat privileged ears in A/B tests, or the fabulous K2600's triple strike feature with only 12 MB, but with the VAST synthesis engine and KDFX behind), as well as other more painful ones (the dreadful M1 "pianos, " for example).

|

When personal computers allowed extensive sampling at high sampling rates, things started to change up to the point that we saw the emergence of 250 GB libraries dedicated exclusively to acoustic pianos, like the four EastWest pianos with 73 GB, 87 GB, 58 GB and 46 GB for the Bechstein D-280, Steinway D, Bösendorfer 290, and Yamaha C7, respectively. Synthogy, another developer of generous sound banks (led by Joe Lerardi, mastermind behind the Kurzweil pre-K2600 acoustic pianos, which means those that only had 4 MB of samples…), offers a 28 GB Bösendorfer, a 29 GB German D and a 23 GB Yamaha. Do bear in mind that a high-end G4 400 was sold back in 2000 with a hard disk of… 10 GB, so it should be easy to appreciate what the constant decrease in computer memory prices has done to improve the quality of sampled instruments (don’t forget orchestra sounds as well). The prices have unfortunately risen again since the introduction of SSD, but we hope to see them drop again soon, considering that their speed, and corresponding time saving, is phenomenal (but what about their longevity and stability?). Enough with the digression.

True Keys was originally a bundle of three pianos, but recently VI Labs has started to sell them as single units: a Steinway D (21 GB in .ufs format), a Bechstein baby grand (18 GB) and a Fazioli F308 (24 GB) compatible with the free UVI Workstation player, and thus with MachFive 3, which we used for this test.

Introducing VI Labs True Keys

To buy it online you’ll have to head to the developer’s (or local importer’s) website ─ or you can also buy the bundle in the form of a USB key. It costs 329 euros ($349.99 at the developer’s website). Single pianos go for 149.99 dollars each. Once you download the installer (one single 7.8 GB file…), you have to unzip it to a folder that contains another installer, five .rar files with the samples and program files, as well as the manuals (including the manual for the UVI Workstation, supplied with the library). Then, you have to launch the second installer to install any or all of the pianos. Once the installation is finished, you’ll find 50,000 samples (63 GB) in the form of three .ufs files, the UVI container file format.

After creating an account and registering the product on the developer’s website we can authorize the product via iLok, which has exhibited serious problems since the update of their system and their site, an issue that ought to be solved (hopefully…) at the time of publication of this review. Luckily I didn’t have any problems (which have to do with the iLok databases and not with the user’s configuration). The minimum requirements are the same as those of MachFive3 and the UVI Workstation. They are Mac and PC compatible (32 and 64 bits).

The key to the Keys

The instrument interface is always the same: after it has finished loading, we find ourselves with a nice image of chords, tuning pins, agraffes, a frame and/or a soundboard, on top of which we have the settings button. The latter opens the instruments’ settings window, where we find a great number of parameters that allows us to fully customize the sound of the piano used.

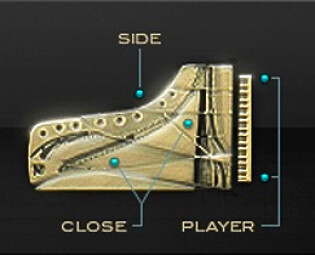

Like many other libraries, True Keys appeals to a principle that mixes several sound positions, three in this case: Close, Player and Side. Plus there is also Mix, to blend the three positions. The piano presets also share this same characteristic, each of them complemented with a Lite version, as well as a “master” preset named after the piano in question, for example: True Keys – German.M5p. Unless otherwise noted, we will be using these global presets for this review.

The sampling is overwhelming: the American piano has 3422 Keygroups, the German 2647 and the Italian 3515. By the way, our examples will follow this same order. We have access to all layers, samples, effects, filters, etc. The sustains comprise up to nine layers (and by semitones), except for the highs, starting from F#5 (for the Italian), which have six layers. We can select, hear or even export sample by sample (which are all 16 bits, 44.1 kHz). The samples don’t seem to be loops, but I couldn’t check the whole library (it’s 50.000 samples, remember…). There is one resonance sample per semitone. The developer made a technical choice regarding this critical aspect of a virtual piano: to sample where others use a mixture of modeling and sampling. Here’s an example of such sampling, in order for you to understand what it is exactly. Its volume and activation depend on several parameters to which we will come to later.

On the first row of settings we have the volume of the Release samples, the Pedal Noise and the Key Noise (the noise produced by the keys and the hammer). The pedal noise ─ a classic ─ also depends on the velocity, provided we have a CC sustain pedal, that is.

On this first example of an American Mix, we will initially hear these settings adjusted to the minimum, then halfway and finally to the maximum.

Moving on we find the behavior of the piano with regard to the sustain pedal, with a resonance setting for the dedicated samples, and two switches to activate the True Pedal and Repedal modes, which are meant to provide more realism. We can thus hear the instrument resonate if we press the pedal after playing and while sustaining a note (True Pedal), and if we press the pedal very quickly after releasing the note. In the following example you’ll hear first True Pedal with the struck chord, and then Repedal very quickly after releasing the notes.

Both have a direct influence on the sympathetic resonance of the strings (and also vice versa), whose number of harmonics (up to 40) and volume (global, not individual) can be adjusted. The result is once again produced by samples not modelling. Here you have one more time the same example on each of the pianos (it is necessary to set the velocity threshold to 2 in order not to trigger the notes of the chord; the polyphony is set to 10).

Inquiring into the velocity a bit further, let’s see what happens if we have the same note pass through the 128 degrees on the three pianos (with the Close position).

And a chord played at the lowest possible value, and the highest.

Another important aspect is the repetition of notes, which must never be… repetitive. In this regard there is a button called Repetition Strikes. Here is an example with and without it.

I might be mistaken, but it seems to me that they didn’t include different random samples as other developers have. Instead, they implemented a low-pass filter (6 dB per octave, switchable per sample!) and a light pitch alteration (we couldn’t find at what level it happens). Due to the absence of information, I will not dwell on the subject.

Another element to verify: phase and panorama. Here are the 88 notes on all three pianos at the same velocity in Player position (it would be necessary to hear them at all velocities for all three positions but, as you’ll surely understand, that this is beyond the scope of this test. Nevertheless, the examples offered ought to be fairly indicative of the overall behavior).

There are small, very slight, phase differences, but the notes lack coherence in the stereo image: some attacks appear more on one side or the other, breaking the continuity along the stereo panorama (which is a bit too large sometimes).

Keys of truth

We also have a reverb ─ iReverb (convolution) with several room types specially adapted for piano ─ with a Tone control (that regulates the gain of a parametric EQ with a large Q and set at 7.16 kHz) and a Dry/Wet knob.

In the middle row we have the different positions, each with its independent volume control, a button to load samples and a bypass, as well as an image depicting the placement of the microphones on the piano.

Here’s an example with the Close position and a short reverb (the settings are strictly the same for all three pianos in each example). Why use a reverb? Well, because we almost never hear a piano without hearing at the same time the room where the piano is…

Let’s now use a mix between Close and Player (almost all the excerpts used in this test are the same songs and technical examples used for the other piano tests signed by me on AF).

For the following example we used the Mix setting with a very distinctive Clean Hall reverb.

Our last example is a personal mix of the three positions with a Large Ensemble reverb.

On the third row we find the last control elements, including the sympathetic resonance we already mentioned, the polyphony (from 32 to 128), the velocity curve and threshold, the sensitivity, and the dynamics of the instrument. Together with a pretty rare set of controls that allows us to choose the MIDI control for the Sustain (classic), Una Corda and Sostenuto pedals, as well as for the half-pedal center, which is critical on a real piano and not very often implemented on a virtual piano, especially considering that the samples are included, just like the ones for the Una Corda. What a luxury! As one might expect, the RAM and CPU load increases considerably, but that’s the price to pay for a realistic instrument. An example with “normal” sound and then with Una Corda (American, three positions).

Conclusion

An undeniable success. It is becoming increasingly difficult to make a choice in this domain, because it is turning more and more subjective rather than objective (defects, issues with the player, sound quality, etc.). This time we found a few strange flaws, which are nevertheless offset by the quality of the sound, the programming and the software power if we use MachFive3 (although the UVI Workstation works fine as well). Among the flaws we can mention the attacks in pianissimo (a bit too present), a somewhat inconsistent stereo image throughout the whole extent of the keyboard, some (minor) phase problems (especially with the Bechstein and Fazioli), a crowded sound in the lower frequencies in some cases (lack of cleanness), some metallic resonances (particularly on the American), perhaps a lack of layers in higher velocities, the volume of the Fazioli is much louder than the two others (which is normal, but might be problematic within a library), and the management of repeated notes, which is less convincing than on competing products.

The rest can be heard on the examples here and on the developer’s website. The character of each piano is very present, the sensations are very nice if we have a good master keyboard. Once recorded, the impact, the presence and the subtlety of the instruments are everything we expect from a recording. Indeed, it is increasingly harder to make a choice…

Download the audio files (in FLAC format)