Don't let technology get in the way of your inspiration—tame that technology, and make it work for you.

Is “writing in the studio” an oxymoron? It seems that writing a song and recording it are two totally different activities, and need to be treated as such. What got me thinking about this was how easily I could write songs when just sitting down at a piano or guitar, yet how difficult that process became when sitting in front of a sequencer. But I’ve learned it doesn’t have to be this way.

This article covers what I call “fast tracking”—using a sequencer/DAW in a way that’s optimized for writing, not recording or editing. By employing this process, I finally feel I can write on a computer as easily as on an instrument. Of course, different people approach the creative process differently; but I’m probably typical enough that many of you will find the following tips helpful.

Capture that Inspiration Immediately

Inspiration comes and goes fast. The one way to prolong the state of being inspired is to start exploiting the inspiration as soon as it hits. Do everything you can to speed your computer’s start up time, such as periodic defragmentation and if you use Windows, have it rearrange programs for fastest startup.

Next, check out the companion article Customize Your Daw with Templates. There’s nothing like having an “instant environment” that’s optimized for writing—with instruments, patterns, track assignments, and so on ready to go. If you can’t start laying down tracks within 30 seconds of your computer booting, there’s a problem that needs to be addressed.

Start with MIDI, not Audio, Tracks

Sure, a MIDI piano probably won’t sound as good as your 9 ft. Bosendorfer. But when writing, keep a piece of music as malleable as possible. You may need to change key or tempo as the piece takes shape, and while it’s possible to make these kinds of changes with digital audio thanks to time and pitch-stretching, MIDI simplifies the process compared to using digital audio.

Use a Software 'Workstation’

SampleTank 2 is a good example of a “workstation” plug-in. It comes with a large sound library, and can play back up to 16 different parts (instrument sounds) simultaneously.

Quite a few plug-ins (like IK Multimedia’s SampleTank 2 and Steinberg’s Hypersonic) are essentially multitimbral workstations with a boatload of sounds. But even a simple device like Edirol’s Virtual Sound Canvas, or the Mac’s QuickTime instruments, can be all you need to sketch out a tune.

The advantage to using a single multitimbral plug-in is that it’s really fast to create tracks: Insert a MIDI track, assign it to a channel in your plug-in, assign a sound to the channel, and bingo—press record. You can simulate the same process if you have a template with a variety of instruments assigned to a variety of tracks, but I find it more efficient to keep things simple.

Scratch Tracks Save Time

The object is to write a song, not to play a bunch of perfect takes. A good song in the conventional sense consists of memorable elements like melodies, strong lyrics, and a good flow—not nailing the perfect bass timbre. You can always go clean up your parts later, but when you want to lay down a part using a particular instrument, just do it. Don’t agonize over the sound quality, or your playing. Copy and paste to create placemarkers rather than play all the way through. Of course, most of this won’t make the final cut, but so what? The object here is to build a song and arrangement, not a recording.

What about Vocals?

If you can get down some key lyric ideas and a melody line, that’s fine. Don’t have lyrics for the second verse? Hum the melody, or just say nonsense syllables. You can always fix it later. Even if you only have lyrics for a couple lines, get them down and move on.

Stick to the Essentials

All those “ear candy” parts—the cool double-time shaker, the melodic bells that come in during the solo, and so on—should be added only when the core tracks are down. Ear candy can be another distraction that, unless it’s an element that’s vital to the song, should be left for later. And don’t even think about adding reverb, EQ, etc. The only reason to add a signal processor is if it’s an essential element to the song, like a tempo-synched delay that is mandatory for the particular rhythm driving your tune.

Don’t Edit As You Go

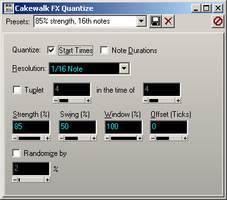

By using a MIDI FX plug-in, parts can be quantized during play back while songwriting. However, as the original part is not change, quantization can be removed or edited at any time.

The single biggest inspiration-killer when you’re writing on a DAW is editing. Editing is a left brain activity, not a right brain, creative type of activity. Laying down a part, then trying to perfect it, is a sure way to have inspiration take a hike.

For example, consider quantization. When I’m writing in Sonar and want to quantize a part, I just insert the Quantization MIDI FX in the MIDI track, dial up 16th notes with 85% quantization strength, and don’t think about it any more. Because the original data is unchanged, should the part be any good, I can always remove the FX and do more detailed quantization later.

Remember, what makes a great song is not a superb instrument timbre; that just makes a great song sound better. Concentrate on what matters most when you’re writing: The emotional impact on the listener. Remember that no listener ever said they liked a song because the vocals were recorded with a Neumann mic.

The Bottom Line is Attitude

Although we’ve covered some specific tips, the main point is attitude. Once you shift your brain so that it understands the difference between the writing process and the recording process—and I do believe these are indeed different animals —that’s half the battle. The other half is having the discipline not to get sidetracked during the writing process. All I can say is that since figuring this out, my DAW is now as good a songwriting device as an instrument. In fact, in many ways, it’s even better.

Originally published on Harmony Central. Reprinted with permission.