In the previous articles we talked about major and minor chords, how scales are formed and how you can tell the key of a song from its key signature.

But harmony is ─ above all ─ the art of playing sounds together at the same time. And that’s why it’s particularly interesting to understand how chords are built.

Chords

A chord is made up of different notes played simultaneously, which, put simply, can be seen as thirds being stacked upon each other. In order for a chord to be clearly identifiable, it must have at least three notes, or two thirds. This is called a triad.

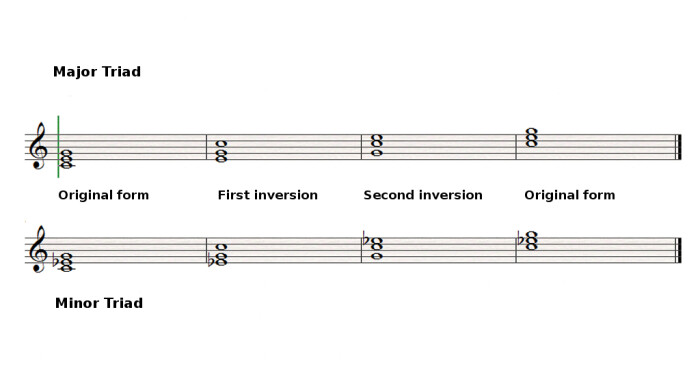

A major chord is made up of a root note, a major third above it and a minor third above the latter. For example, if the root note is C, the major third above it is E and the minor third above this second note is G. This is called a major triad or major chord.

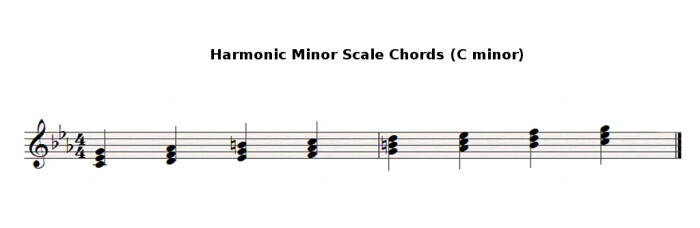

To build a minor chord from C you need the minor third above the root, Eb, and the major third above this second note, which is G again. This is called a minor triad or chord. Finally, a chord that has its root in the seventh of a major, harmonic or melodic (but not natural!) minor scale is built with two minor thirds. This is called a diminished triad or chord. The gap between the root and the highest note of the chord constitutes a tritone (three tones; refer to the first article of the series). We’ll come to this in a future article.

You have probably noticed that the only difference between the major and minor triads is the middle note of the chord.

Inversions

Did I say the middle note? To be clearer, I was referring to the third, in other words, the note that is either one and a half or two steps above the root. The third note of the chord is called the fifth. Regardless of whether the chord is major or minor, the fifth is always perfect, which means it’s exactly three tones and a half above the root of the chord. Why am I telling you all this, you ask? Well, simply because the notes of the chords aren’t always in the order described above, they can also be inverted (and chords can even lack some of their notes!).

The way inversions work is that you always shift the lowest note of the chord one octave above. In the example above, the C Major chord, the first inversion is achieved by transposing the root © to the octave above. The second inversion is achieved by transposing the third (E) to the octave above. And, finally, transposing the G one octave above results in the original from of the chord, but one octave above.

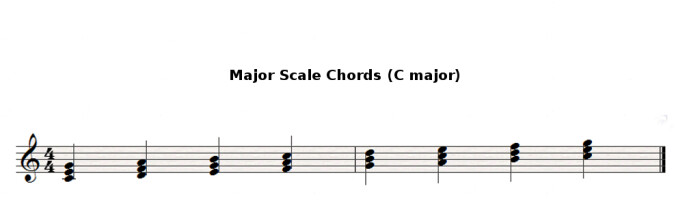

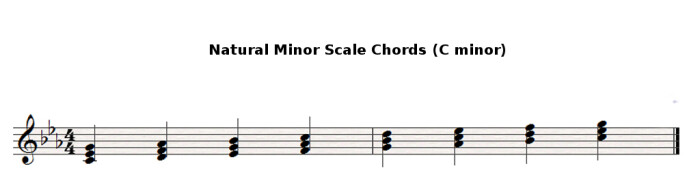

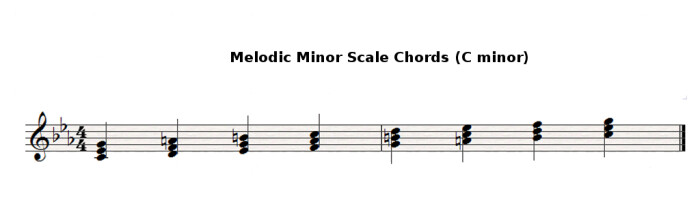

Generally speaking, theorists tend to agree that the first from gives stability to the chord, the second one an air of lightness and the third one has a sense of instability to it that often recalls another chord. Inversions can obviously be applied to all sorts of chords, major, minor or…any other. Before moving on, here you have the harmonies you can start building with the scales you already know.

Four-note chords (seventh chords)

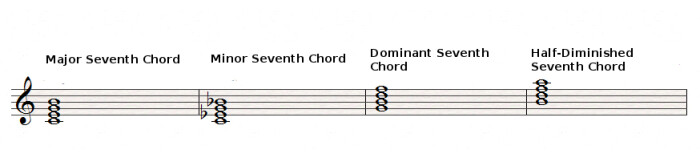

There are also chords that have four notes. They are based on the three-note chords we just saw, to which another third (major or minor) is added. The interval between the “new” note and the root is a seventh, that’s why they are called “seventh chords.” It can be a major chord, if you add a major third to a major triad, or minor if you add a minor third to a…minor triad. If, however, you add a minor third to a major triad, you get a dominant seventh chord. This type of chord has a particularity that makes it quite important when building the harmony of a song.

The chord created using the seventh degree of a scale (don’t confuse the seventh degree of a scale with the interval of a seventh between the root and the highest note of the chord!) is made up of a diminished triad (see above) plus a minor third. This type of chord can be found in the major and melodic minor scales (but not in the natural or harmonic minor).

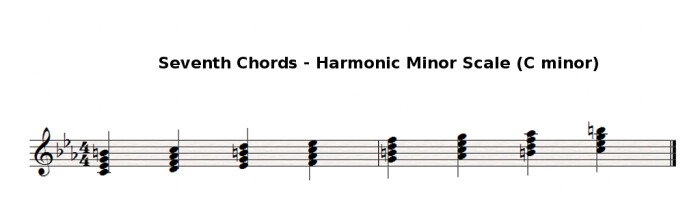

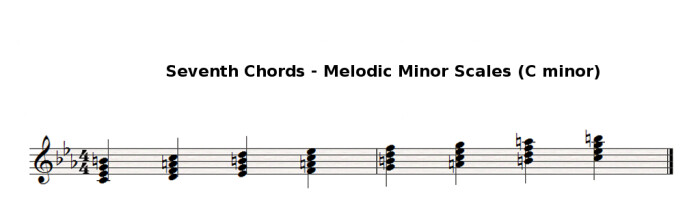

Here’s what seventh chords look like:

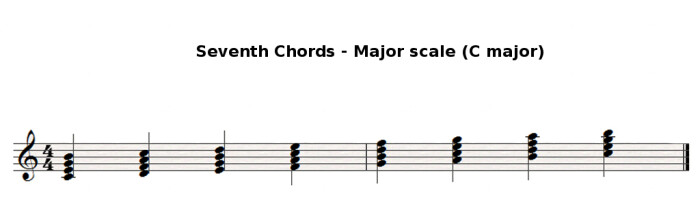

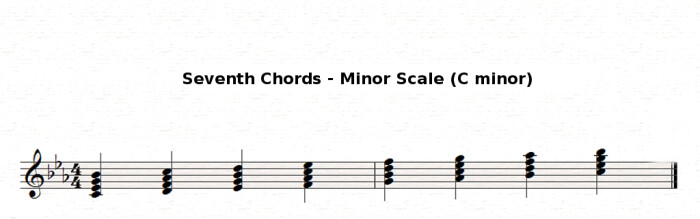

And here are the harmonizations of the major and minor scales in seventh chords:

Chord Notation

To conclude this article, I will mention the two ways of writing down a chord, the classic method and the Anglo-Saxon one. The classic method, which is a bit more complex and hardly used nowadays, is something we will deal with in a forthcoming article. For its part, the Anglo-Saxon method is used mainly in jazz and pop.

To specify a chord, you use the letter corresponding to the root note (A, B, C, D, E, F, G) and, if it’s a major chord, add “maj” or “M” to it, or simply write down the letter of the chord. An F major chord, for instance, can be represented by F, Fmaj or FM. Minor chords are usually appended with “min.” You also often you see them with a lower-case “m” as in “Fm”. If a major or minor chord is followed by the number “7,” it means it’s a seventh chord. In this case, major chords are always appended with “maj” or “M.” Otherwise, if the chord has only a “7,” it means that it’s a dominant seventh chord.

So, to make it as clear as possible: F is an F major chord, but F7 is a dominant seventh chord. For an F major chord you would need to write Fmaj7 or FM7. Especially in jazz, major-seventh chords are sometimes written with a triangle symbol. So Fmaj7 would be FΔ7 or FΔ.

In the next articles we will see how you can use these chords to harmonize a melody.