It's not uncommon for a composer/songwriter to feel the need to leave the original key of the song he's writing and go explore some other ones. There are many reasons for that: to change the mood (i.e. the key!) of the song, to catch the attention of the listener, to create surprises, etc. And this is where the principle of modulation, which we will be discussing in the following articles, comes in.

Characteristic Notes

A modulation almost always takes place when, at least, one new note is introduced to the original key (except when you modulate to a relative key – see article 2). This note is, oftentimes, the leading-tone of the new key, but not necessarily.

These new notes which appear in the original key and define the new key are called “characteristic notes.” However, the introduction of these characteristic notes doesn’t imply the changing of the song’s key signature. In fact, modulations are usually temporary only. The key signature is only modified when the song positively changes to another key.

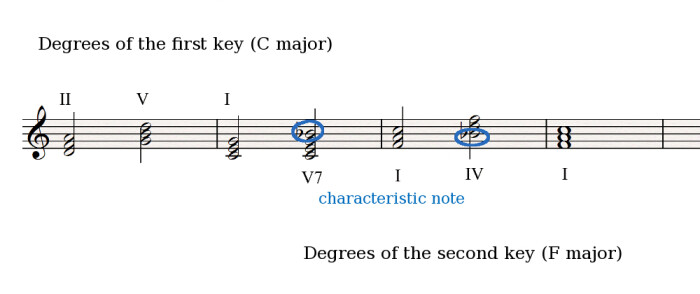

In the following example, I go from the key of C major to F major by using Bb, which is a characteristic note of F major:

But that’s not the only reason, as you we’ll see in a moment!

The Return of Cadence

As I mentioned in the previous article, for a modulation to actually take place the ear must have enough time to actually understand that the change has taken place, and that we are not only introducing a non-chord tone (as we saw in article 8). In the previous clip, for instance, the modulation goes on for two whole bars, which is more than enough. But it’s also important for the changes to follow a logic that defines the new key, which once again leads us to the favorite weapon of the wise harmonizer ─ cadence!

In the previous example, we had a perfect cadence between the dominant seventh chord of C and F major in the second and third bars. The resolving nature of this cadence allows us to effectively assert the modulation between the two keys of the song. But since we are talking about cadences and their use for modulation, there is one cadence that seems to impose itself naturally in this context, the interrupted cadence (see article 7). In this case, we go from a major key to its relative minor by simply replacing the I degree of the original key with the VI degree (which is, in turn, the I degree of the relative minor). Furthermore, as we saw in articles 14 and 16, the VI degree of a key shares the same tonal function as the I degree, which means it can easily be used to substitute it. You see how everything just seems to fit together nicely?

I’ll leave it here for today but would like to invite you to join me next week to discuss some more harmony.