In the final installment of this three-part article, we’ll look at a few other key issues to consider when contemplating switching over to an in-ear monitor system.

Frequency is everything

Wireless systems of all types are proliferating, and there isn’t enough frequency space to ensure that you won’t have conflicts with other wireless devices. What’s more, your geographic location impacts which frequencies are best to use at a given time. With that in mind, you definitely want to get a system that gives you the ability to select from multiple frequences. There are fixed-frequency systems available, and they’re cheaper, but they will limit your ability to travel with your system. As you get higher in the price range for in-ear systems, you get more frequency choice, with some even offering automatic frequency scanning.

Before you buy a system, consult with your dealer (or the manufacturer) about the issue of frequencies, and whether there are available frequencies in the area (or areas) you’ll be playing. That’s obviously a make-or-break consideration. The frequency spectrum is becoming increasingly crowded as more types of wireless devices come online, so finding a system that will work in your area is crucial.

With wireless systems, you always run some risk of intermittent dropouts, interference and distortion. Using the manufacturer-recommended battery types and making sure your batteries don’t run low during shows helps prevent such problems, as can learning how to properly set antennas and keep line of sight between transmitters and receivers. Shure, which makes many different wireless products, including in-ear systems, publishes this helpful guide to getting good wireless performance.

When it comes to in-ear systems, wireless operation is both a blessing and a curse. It’s the former because it allows you to use in-ear monitors completely untethered. It’s the latter because, as with any wireless product, it adds to the number of potential problems you have to watch out for.

All or nothing

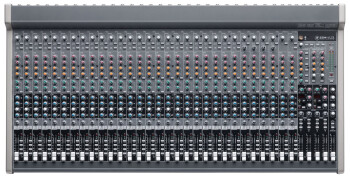

Another issue to consider regarding in-ear systems is that every instrument must go into the P.A., either by mic or DI. If an instrument is left out it won’t be audible in the in-ear mix, except possibly as bleed through the vocal mics. If you own your own P.A., and your mixer doesn’t have enough channels to accept an input for each of your instruments (with more than one input for the drums), that’s pretty much a deal breaker — at least for a conventionally set up system.

You don’t necessarily need four or more mics on the drums (although it would be preferable), you can probably get by, if need be, with a kick and snare mic and pick up the rest of the kit through vocal mic bleed.

An alternative to a standard in-ear setup would be only to put the vocalists on “ears” (with enough instruments in the mix so the singers could feel what’s going on and hear pitch reference), and the non-singing band members would still have to use wedges to hear the singers, with the volume low enough so as not to create spill out front. I’m not recommending that type of configuration, per se, but am just pointing it out as a possibility. Whatever works.

Engineering

In a standard in-ear setup, with everything going into the board and no wedges blaring at you, you have an opportunity to keep the stage sound at a reasonably low level. But you’ll need someone running sound out front to get the best results from this setup, because most of the instruments (other than what leaks offstage from the drums and amps) and all of the vocal sound will be coming to the audience through the P.A. Even with a standard wedge-based setup, it’s difficult to judge from stage what the mix sounds like in the house, and with “ears” on it’s even tougher to tell because of their isolating nature. As a result, having a soundperson will be very helpful for getting a good mix out front.

If you’re in a band that plays mostly at venues that have their own sound systems, and your gigs are typically the kind where you’re on the bill with several other bands, you may run into resistance from the house soundperson to using your in-ear system, because it requires a little extra work on his or her part, and will mean more setup time. Be ready to go back to using wedges in such a situation should the need arise.

Conclusion

As we’ve seen in this article and the two parts preceding it, transitioning successfully to an in-ear system requires not only that you buy the gear, but that you buy into the concept. There may be a few hiccups along the way, but once you get used to this new and better way to hear yourself onstage, you’re likely to wish you had made the change a lot sooner. Happy monitoring!

Thanks to Gary Boss of Audio-Technica and David Campbell from Galaxy Audio for technical consultation on this series.