The previous article allowed you to get to know chords better, discussing open and drop chords. This week we'll take a look at a case where voices evolve in parallel, with a special focus on octaves and fifths. I know, I know: parallel octaves and fifths are forbidden, right? Indeed, when you want to stick to classic harmony, it is...

The taboo of parallelism

Classic harmony has a very strict opinion regarding parallel motion. As a general rule, it prefers contrary or oblique movements, as we already mentioned in article 22. Why? First of all, classic harmony strives for the independence of the different voices. This independence is obviously lost when you make the voices move in parallel. However, as we also mentioned in the same article, parallel progressions of thirds and sixths are tolerated, because even if they certainly lose independence, the third and the sixth of a note at least enrich harmonically the note.

But it’s a different story when it comes to the fifth and the octave. In fact, the octave and the fifth are the two overtones most present in any given note (refer to article 4 of the “All You Need to Know About Sound Synthesis” series). So, adding the octave or fifth to the note doesn’t really add anything to it, harmonically speaking.

Do note that the progression of a fifth is even more strictly forbidden than that of an octave (which do add some overall energy) because fifths are “blamed” for providing a sort of “medieval” color, which classic harmony tends to avoid.

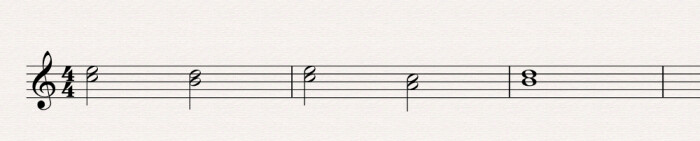

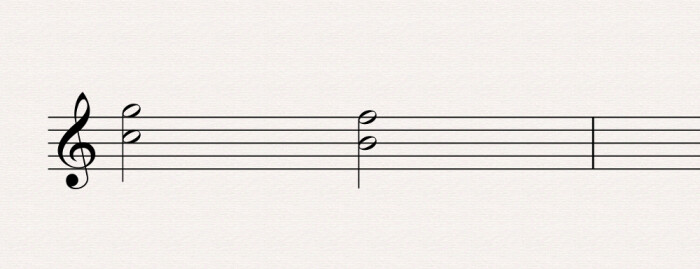

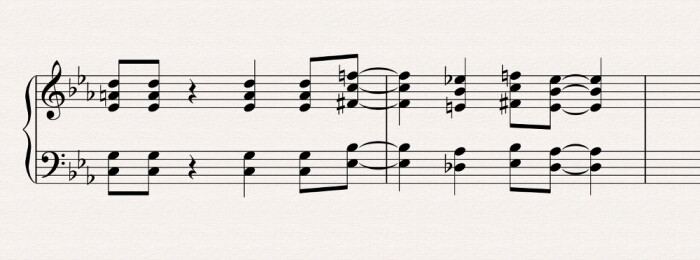

However, there is an exception to the rule: when the second fifth is diminished and the motion is downwards. In the following example the C-G perfect fifth is followed by the B-F diminished fifth with a descending motion:

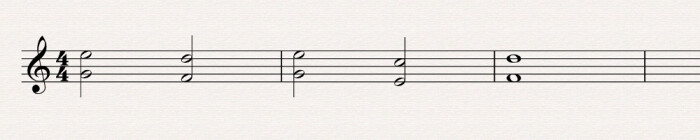

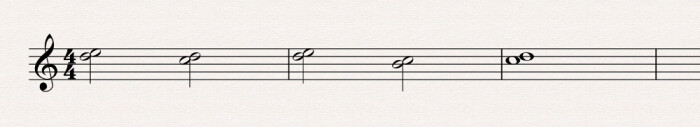

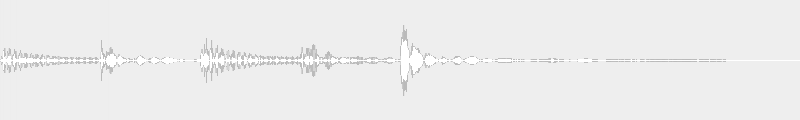

Finally, as you saw in article 23, second and seventh intervals are among the most dissonant there are, which absolutely calls for a resolution. This means they can never be the subject of a parallel progression, as you can hear in the following examples:

Parallelism today

These intervals sound just as dissonant to our ears as they did in the 19th century, so the rules haven’t changed much in this regard. On the other hand, the rules applying to fifth and octave parallel progressions are hardly observed in modern musical styles, where harmonic simplicity is the rule, and where the power of an octave progression or the harshness of a fifth progression is very welcome.

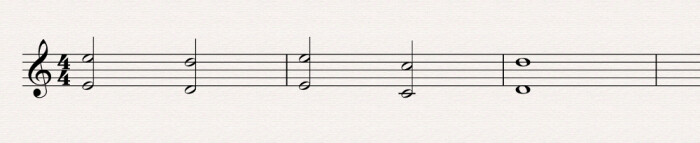

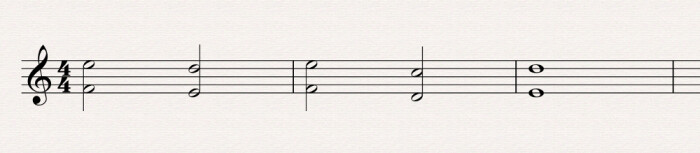

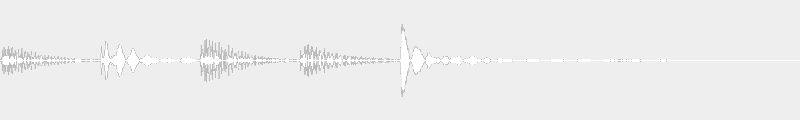

The most notable example is the use of powerchords in rock, like this:

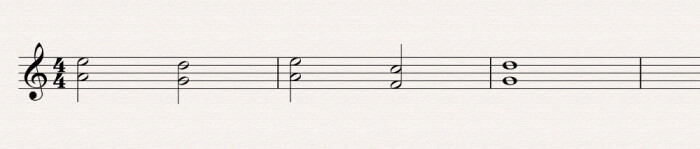

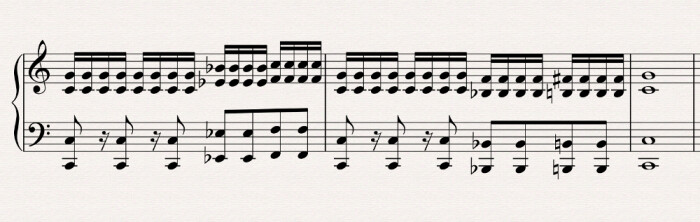

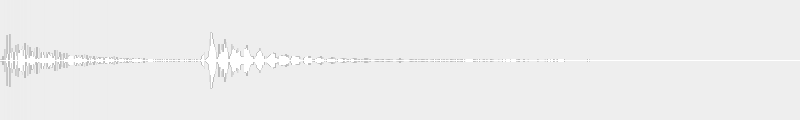

But also in jazz, although in a more subtle way, like in this progression of voicings based on minor chords enriched with the 9th and 13th, and where the two lowest voices are one perfect fifth apart: