Indianapolis-based David Kimmell worked his way up in the pro audio world through an eclectic mix of music-related gigs such as club sound man; pro audio manager at a Guitar Center; sound company employee who did “pyro, live sound front of house, monitors, lighting, everything”; and backline manager for a company that provided gear to touring bands. Nowadays, he’s an in-demand engineer for mixing and recording, both live and in his studio, Masthead Audio. Audiofanzine had the opportunity recently to talk to Kimmel about the challenges of live recording, the difference between mixing live- and studio-recorded material, his studio gear setup, his background, and more.

What does a backline manager do?

Basically what you’re handling is all the amplifiers, keyboards, drum sets, pretty much anything that doesn’t go on a plane easily. That makes it possible for artists to do one-off shows. They bring their guitar or whatever, but we [the backline company] would supply the amplifiers and cables and everything else they need to make it happen. I worked for a bunch of the older artists like Aretha Franklin and the Four Tops, Temptations. I did a lot of shows with Three Dog Night. A bunch of really great musicians to work for, and it was just a lot of fun.

How long did you do that for?

I did that for about four years, and I got really tired of it. It was a lot of driving. I still had all this studio equipment and I had a client who was like “I need somebody to do some of these smaller projects and just mix them down for me.” I thought that was pretty cool. He was able to give me enough work so that I could come in off the road, and have been working for him ever since, doing church services and whatever they need me to mix down and turn into a disk.

So you’re doing studio mixes of live-recorded events?

Whatever the event is, a church service or whatever. It was like a P.A. company, a live sound company. And whatever he gets ahold of, and needs to have done, he sends it to me and I make it happen.

Have you done a lot of live sound mixing?

Yeah, that’s the thing I’ve done more than anything else through the years. I’m more of an expert in that world. But I’m getting much much better in the studio.

You also have bands that come into you with projects to mix.

Yeah. I do studio type stuff where they come in here and mix. I have situations where they record the stuff at home and then send me the tracks and I mix them and sometimes master them here. Or record live shows for bands, and come back and mix it down. I just did one, right before Thanksgiving, it’s a thing we do every year, and I recorded about 2.5 hours worth of material, 18 tracks, and mixed it down to two CDs. I’ve gotten to a point where I’m pretty good with the live sound recording.

How do you get the feeds for the live recording, direct outs?

In the past, I used to bring my interface and my computer, all my gear, and do a split off the board using direct outs. But now, with the proliferation of digital consoles, I can plug USB into the computer and into the back of the board. I’ve got a template in my program setup, I just bring that up and it records all the tracks.

So in other words, if the venue has a digital console, you can use its USB port to access individual feeds of all the mixer channels?

Yes. I don’t have to bring my rack, all I need is my computer…It’s pretty awesome.

So in those situations, you don’t have control over the miking, you just take whatever you get signal wise?

Well, generally, I only do it if I’m running sound. I have my mic collection which is way better than the house mic collections around. I bring my stuff and make sure there are quality mics and good cables, so I don’t have to fight things. I’m a big fan of having good gear. I feel like the transducers are the most important part.

For sure. In a live recording, problems with bleed and phase are common. Do you have any particular strategies for avoiding them?

One thing is to minimize the number of microphones. I never double-mic a snare. I’ll do two mics on a kick, but not a snare, and eliminates a lot of my phasing problems. I try to keep everything as close-miked as I possibly can. The mics are right on top of the heads on the drums. My guitar amp mics are right on there. I also try to keep things as spread out as possible, even if it’s a small stage. But you’re going to have bleed through, it’s just going to happen. And when I’m mixing down, I don’t do a lot to it. It’s one of those things where if it’s not broke, don’t fix it. I bring stuff up, make sure it sounds good EQ-wise, and then let the bleed work for me.

Explain.

On my last live recording project, I was putting on post reverb, here in the studio, on the vocals. There were three vocals, and I did that because I knew that those vocal mics were one of the hottest things on the stage and it was going to be picking up more than anything else, and there was a drummer with a vocal mic. So, as I’m bringing that up, I was realizing that the snare and the drum kit were actually getting reverb through the vocal mic.

So you’re using the vocal mics like room mics, in a way.

Yeah, that’s kind of how it turned out. So because of that, I never put any reverb on the drums, because it was happening through the vocal mic, and I didn’t have to do anything to make it work out like I needed it to. The more I do live recordings, the more I realize that you just have to let things be as they are. You want to clean up as much as you can, put your filters on, and gates and everything else. But there are certain times you have to work on a situation. Like the guitar is coming through his vocal mic. Alright, let’s make his vocal good, and then bring the guitar up to where I need it to match with what I’m already getting from his vocal mic. I didn’t explain that very well [laughs], but you have to think of it as going from hot to cold. You bring up your hottest mic, because you know you’re going to pick up a bunch of other stuff, too. And then bring everything else up individually to make it sound good, but also to match and balance everything out.

I would assume vocalists with hand-holding mics that are constantly moving around would cause more problems on a recording?

Yeah. I’ve been lucky, I haven’t had a lot of that with the live recordings I’ve done. But I’ve had a couple of occasions where things would change when the singer was moving around on stage. Like they’d get close to the drum kit and that would change the sound. That’s one of those situations where automation is your friend. You can fiddle around with the volumes of things, either the direct or where it’s bleeding through to bring it up and down to match that. I’ve been lucky, I haven’t had to do that a lot, but it can be a pain in the ass. [Laughs]

Does the sound coming out of the monitors cause a lot of bleed issues?

It can. But the wonderful thing about it is that what’s going through the monitors is also coming in to the recording. It’s a masking situation where if you bring up what you have direct on the track — like for your main guitar track there’s mics on the cabinet — you can bring that up enough to where it’s actually masking the bleed. Because it’s the same frequency, same time, and everything else. A lot of people when they do live recordings have a tendency to create more problems in the mixdown then they need to because they’re trying to make it like it’s a studio situation, and you can’t do that.

So how do you approach it?

You have to mix it like it’s a live situation. It’s a different beast entirely. There’s no isolation. And sometimes it doesn’t work out. I always tell people when I’m going to do a live recording of them that this is a one-shot thing and may not happen right. I can’t really monitor well what’s going on because I’m standing in front of a P.A. system, and trying to listen to what’s coming through it.

Is it practical to punch in to fix mistakes in a live recording, afterwards in the studio?

Yeah, well, certain things you can do and certain things you can’t. If something’s isolated, I could potentially throw some Melodyne on it. But it’s pretty rare. [Laughs] It’s going to make things pretty funky. Most of the time, if I’m going to be doing a live recording, when I first do the pre-production, I’m thinking about what kind of musicianship these guys have, and are we going to be able to pull this off. If I don’t feel like they’re good enough musicians to pull it off, I’m going to gently tell them so. “Look, you guys are good, but I think we need a little more time to work on a couple of things so we don’t have to fix things. We’ll do this in six months when you guys are a little bit better.” You kind of have to be part psychologist. [Laughs]

Let’s talk about the differences in approach between mixing live sound and mixing a recording in the studio. Obviously, in a live mix there’s the immediacy: whatever moves you make on the mixer are instantly heard by the audience, whereas in a studio mix, if you don’t like something you’ve done, you can just redo it without anyone hearing it. How is your approach different, sort of in a general sense.

The thing I like about live audio is you bring something up, make it sound good, and then move on to the next thing. With the studio, I couldn’t do it like that. That’s one of the reasons I bought the Dangerous D-Box with its analog summing.

How does that help?

I was having problems in the studio, like I’d bring up a kick to where it sounds good, bring up the snare to where it sounds good, and then I’d put it in the master bus and it would be clipping. And it’s like, “Oh crap, now I’ve got to go back and fix it.” It drove me nuts. I was ready to find another job. I was not happy. It just sucked. So I went and saw a seminar about analog summing and there were a bunch of other people having the same issue. Analog summing eliminates that problem. So I bought the D-Box, it was like I was back doing the live sound again, where I could mix that way in the studio. I could bring it up, make it sound good, bring it up, bring it make it sound good. I’m a pretty quick mover in the studio. I find that the more I dwell on a sound, the worse it gets a lot of times. [Laughs]

[Laughs] So you’re not one of those engineers who spends three hours getting a kick drum sound.

No. If you’ve got something soloed up, like the kick, [you get it sounding good] and then you move on, and do the rest of the kit. It changes, what you add in will change it all. So I tend to be quick with my mix, and then fix the things that sound weird once I have everything in the mix.

How do you generally start your mixes: do you have all the tracks down or zeroed out?

I start off with just one track at a time, and bring them up. It depends. If I know this is a really good band and I’m excited to mix it down, I’ll bring stuff up and see how it all sounds to begin with. It’s going to give me a basic idea of what I have to work with. And I’ll then go back and solo things up and if I hear some rattle or noise I don’t like, I’ll solo that track, fix the problem and go back, and bring it back into the mix and see how it combines with everything else.

What DAW do you use? Are you a Pro Tools guy?

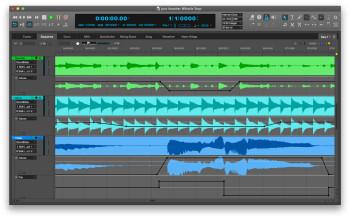

No, I’m a Digital Performer guy.

So with the Dangerous D-Box summing, you have to assign the outputs of tracks in your DAW to the different input pairs on the D-Box, right?

Yeah. Usually I do 1 and 2 drums, 3 and 4 will be the bass and maybe the keys. Five and 6 will be the guitars, and 7 and 8 will be the vocals. If I have a reverb on something, it goes to the two tracks they correspond to.

And then the mix comes back into a track in DP where you record it?

Yes. Before it does that, it goes to my Bax EQ, to clean up everything. It makes the converters work better. It was expensive, but it’s worth every penny.

Talk about what the Bax EQ does for the sound.

Think of it like an analog mastering EQ, but with only eight knobs on it. On your left is your low cut, which gets rid of all that subsonic crap. It’s a very good filter. And the same thing on the very right end is your low pass. And the two inside of both of those are going to be your frequency choice, your high shelf or your low shelf. And then you have two knobs in the middle for your left and right, boost or cut for those low and high frequencies. It’s exactly what you need in a 2-track mix that’s going back in the box. It’s really cleaned up things for me. It gives me like another 5 percent of good sound, you know what I mean?

It comes into the Bax EQ after it’s been summed, I assume and then into your computer?

Yeah.

Since you’re sending the tracks out of separate outputs in your DAW, it’s impossible to have a master track. So do you use the track that records the signal coming back into your DAW after the D-Box and the Bax to add your master effects?

Exactly. That whole, in-the-box master track thing is gone in this setup. So what I do is have a return track, a regular stereo track, not a master track, record it in real time, so you do lose that wonderful little bounce thing you can do in the box. You lose a little bit of time, but the quality is [better], so I have no problem taking a little break while it runs. Then I have that stereo track with the mix and I can take it and cut it up and add something to it. I’ll usually throw my mastering plug-ins on that.

So you think that the biggest difference between your D-Box summing setup and mixing in the box is that you’re able to run hotter levels and not overload the master?

It’s not necessarily hotter levels, it’s just having that headroom. Having that give, so I don’t have to go back. A lot of times I can keep boosting. I don’t like to boost a lot, but I could do that. I can get a mix and say, “I want this one thing louder.” But I can do that, and I don’t have to worry that instead of bringing that one thing up, I have to bring everything else down, because I’ve already maxed it out. I never usually get to that super top part, you know that super hot level that you always had to get before. I don’t have to worry about that.

What do you use for monitors in your studio?

I’ve got Dynaudio BM5 Mark IIIs, the newer ones. They’re my main monitors. And I also bought some cheapo]Yamahas to use for a secondary reference.

And you can switch between them from the D-Box.

Exactly. And switch to mono.

Any other plug-ins that you really like using?

I have Melodyne, but I don’t use it. I feel like if I’m in a project where I have to break out Melodyne, I shouldn’t be in that project. At least I try not to. Sometimes you have to take the gig, but I try to make it so I don’t have to do that. It’s one of those things, it’s a courtesy, if there’s one little thing that needs correcting I’ll open up Melodyne.

Do you have a go-to reverb plug-in?

When I was using one of the Waves reverbs, I forget what it was called, I couldn’t stand it. I didn’t like the way it interfaced, I didn’t like using it so, about a year ago I bought an Eventide Eclipse. I love that thing, I love the way it interfaces. I feel like the sound quality is so much better. It’s all digital. I use the Lightpipe I/O on my MOTU [interface] in and out so it keeps everything digital.

I read your credits and noticed that you have mixed a pretty wide range of musical styles. From bluegrass to EDM, and I assume things in between.

Oh yeah, rock 'n roll. Like the project I did the day before Thanksgiving, which was a progressive rock trio. And the funny thing is, the bass player plays mandolin in a bluegrass group that I work with a lot.

The approach to mixing has got to be pretty different between prog rock and bluegrass? You have a mandolin instead of a snare drum.

I think it’s all the same, 20–20. You get 20 Hz to 20,000 Hz to work with. What you’re doing as far as content is different, but what you’re trying to pull off at the end is just a good, even, balanced sound from top to bottom.