What do Keith Richards, James Taylor, Katy Perry, John Mayer and Eric Clapton have in common? They’ve all had albums produced, mixed, or engineered by Dave O’Donnell. A native of upstate New York, Dave cut his teeth at New York City's Power Station Studios (now called Avatar), a facility that was the launch pad for many top engineers and producers.

We spoke with the Grammy-award-winning O’Donnell a few weeks ago. He’s currently working with Sheryl Crow on her new album. “We’ve done most of the recording and are getting close to the mixing stage, ” he says.

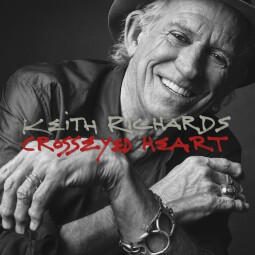

O’Donnell’s other recent major album projects were Keith Richards’ Crosseyed Heart (engineered and mixed), and James Taylor’s Before This World (produced, engineered and mixed). This interview covers a range of subjects including working with Richards, amp miking, compression, mixing techniques, high-sample rate recording, and more.

Do you have your own studio?

I have my own mixing place.

You go other places for tracking?

Yeah, I do. I don’t mix everything here. James’ record, I did mix here, but Keith’s was done at Germano Studios [in NYC] and Sheryl’s record, we recorded mostly in Nashville. I don’t have a tracking room, but can do some overdubs at my place.

Let’s talk about the Keith Richards album. What was it like working with him?

He was great, he was fantastic. It was pure fun. It started off casually. It was him and Steve Jordan for most of the project, just the two of them tracking. They wanted to come in and lay stuff down, so we would just go into Germano Studios a couple times a week for about six hours or so and knock a song out. It kind of went like that for a while whenever Keith was in town. We accumulated a lot of songs, and at some point, people started saying, “You know you really should think about putting this out as a record.” It wasn’t like “OK, I want to make a record.” It was more, just him getting back into the studio and playing.

I noticed there’s a lot of songs—15—on the album.

There is. I didn’t realize they would all end up on it, but yeah.

And it’s pretty eclectic, musically.

It is, it was not one theme, it was a few different things. A few typical rockers, a few more country kind of things and soul things and acoustic things—really good songs, I thought.

So he played mostly electric and acoustic.

Yes, he did most of the guitars. Waddy Wachtel was also on several tracks. It was mostly electric, but a few songs were tracked acoustically, liked “Robbed Blind” and “Just a Gift.” Because they don’t have a separate booth at Germano’s, he was in the control room tracking acoustic. That was kind of fun.

What was the usual signal chain you used on his electric?

I tend to use what I always use: A [Shure SM] 57 and a [Senheisser MD] 421 on the front of the cabinet, and decide which is better for the song. On some of them I’d have a ribbon on the back of the cabinet, usually a Royer 121.

What’s the theory behind putting it behind the amp. Was it a closed back cab, like a stack?

No, I think they were open back.

Combo amps, like Twin Reverbs?

Yeah, small Fender amps, pretty much. What you get [with a mic in back] is more low end, really. And so I just mix in a little of that. It’s all to taste. Some songs may have none, some may have more, but it varies depending on what he’s doing.

Do you have to be careful about phase issues when you have a mic on the back and one on the front?

Yeah. You basically flip the phase of the back one, and try to get the distance to match the front so you can keep things in phase. And that mic in the back is not very loud, it’s just tucked under.

Any room mics?

I would have room mics, depending on what he was playing. Maybe an [Neumann U] 87 or a Beyer m160 out in the room. But they weren’t always needed. I like a close sound for the straight rhythm stuff.

Any colorful things about working with Keith?

Just that it was pure fun. Every sentence he said pretty much ended with a laugh. [Laughs] And this sounds dumb to say, but he’s just an incredible guitar player. You know that going in, but when you’re in the room and you see it—it’s just not some open tuning vibe or whatever. He picks up an acoustic guitar in standard tuning and he’s all over that thing. He’s just an amazing player.

I notice that you have a Yamaha DM-2000 digital mixer in your studio. Do you still use that?

I do use that. Even though it’s digital, it sounds better to me than all in the box. And I do use Pro Tools, but this mixer is pretty versatile. I tend to work at 96k, and you get 48 inputs, which I think is all you’d ever need. This board also has some nice reverb and effects built in. I don’t use the built-in EQ or compressors very much, a little bit. I have a bunch of analog outboard gear that I prefer, and I do use some plug-ins. But the board is not for recording, it’s just for mixing.

If you don’t mix in the box do you get complete recall on that?

Yeah, I just write down the settings for the analog gear. If it’s a crucial thing, I’ll print it. Especially a vocal sound, if I think it’s perfect, like a compressor. I’ll just print the track with it. Then it’s done forever. But it’s all recallable. You just write it down.

You mix through the board and you go back into Pro Tools to record the mix?

I do. No analog 2-mix machine. For a while I was thinking of getting an analog 1/4" tape machine. But I never got around to it and don’t really need it.

Coming out of the Yamaha and back into Pro Tools, does the mix get converted to analog and then back to digital?

It does. Years ago, I used to think I didn’t want to do that. But now, I think the conversion is good enough that it’s fine to do. I’m totally fine with that.

Let’s talk some mixing technique. If you have a typical band-sized song: drums, bass, guitars, keyboards and vocals. Do you have a template that you use to start with? What’s your first move in the mix?

I don’t have an exact template. I always say I should, but I tend to just hear the music first and then set things up the way I want. But generally, I’ll organize the files, then listen and get a good rough mix going, with everything in. I tend to mix a lot of what I recorded already, so I know it all well. But if I don’t, I’ll listen to the song several times, just to learn it and get the rough started. Because basically, you can get a good sounding mix in 20 minutes, I think, if the song is well recorded and well arranged. You can pretty much figure it out right away. So, that’s what I tend to do, and in that time decide what the overall vibe of the song will be, and how wet or dry or whatever. I tend to like things dry.

Talk about your panning strategy.

I tend to pan things hard left and right or center. Kind of like three spots to me, although secondary instruments can be not so hard.

So, you’re not strict on that, you will put some stuff in between, but most everything is left, center or right?

Yeah. If there’s a main guitar part, in general, I’ll put it on one side. I guess I like all the old records like that where you can hear guitar clearly.

Do you worry that there might be a hole in the 3:00/9:00 area when you do that?

No, I love the space. Absolutely. But that would be a spot for something that comes and goes. Backgrounds, or a solo or something. Not something continuous.

When you’re talking about the panned guitar you’re referring to rhythm guitar, right?

Yeah, like a main guitar or keyboard part. Even a lot of keyboard things, they come in stereo, but a lot of them are really mono, or wide mono. For pianos, it’s nice if you get a good stereo image a lot of the time, and organ too, but most other keyboards are pretty much mono to me.

So even if you’re getting a stereo file for the keyboard, you might not pan it fully left and right?

That’s correct. A lot of that has to do if it’s a pad or a rhythm part.

I assume a pad would be more spread out?

Yes.

You were saying that you like to keep things dry. If you get tracks that you didn’t record. Let’s say the drums didn’t have enough of a roomy sound. How would you make the snare sound more ambient?

If there are room tracks, that’s a good way to start—if they sound any good. And, compression and level and EQ can help determine the size. But otherwise, if I do need to add an effect, I’ll just try different things. Sometimes just a regular room reverb, with a 0.8 to 1.2 second reverb time. Depending on the amount, that can do exactly what you need. Usually not a long reverb.

Would that be a mono-to-stereo reverb on an aux?

Yeah, mainly.

Do you do any parallel compression?

I don’t do a lot of that, I know some guys do. Anytime I try it I feel like, I’m just making the instrument louder, so instead I’ll just make it sound like I want it to sound to begin with.

What is your general approach to compression?

When recording I use light compression, which goes back to the analog days of getting it on tape without things being so quiet that they’re hissy, or overloading. Just grabbing the peaks. And that’s excepting tape compression, which is another thing. But for mixing, it can be anything. It can just be the “leveling things out” kind of compression, or it could be squashing it more just to get a sound and an attitude, which would be done with an 1176 or a [Empirical Labs] Distressor. I tend to like those.

Do you use any plug-in compressors?

I do use some. Those are better for leveling things out without changing the sound. Although, since clip gain came out [the editable clip gain line in Pro Tools], I do that first, to even out the file. I will use some plug-ins, but for attitude and vibe, I think the analog gear sounds better. I have a couple of Warm Audio WA-76's, a Purple Audio MC-77, four Distressors, an old Urei LA-3A, a Warm Audio WA-2A, a couple of Neve type compressors like the 2264 (made by Heritage Audio), and a Summit Audio compressor. I also have a GML compressor, which is freaking amazing. When choosing a compressor it depends if you want it fast, and for sound, or just to grab peaks. I guess attack and release is my first thought when you talk about compression. How fast and how much?

Do you use any transient adjusting plug-ins at all?

I have, although I haven’t used it lately. SPL Transient Designer. I have used that, but not a lot. If I use it I’m probably using the sustain knob to make things roomier. That goes back to your question of drums that are too dry. You could try using that to bring out some ambience.

With all the outboard gear that you have, I’m sure you’ve done some comparing when there are software emulations. Do you think that modeled processors are close to the real ones these days?

I’ll say they’re getting better., but I don’t think they’re as good. So, if you have the opportunity, use the real ones. I think the digital plug-in world is getting better and better, though, I’ll concede that point. It depends on how you’re working. If you’re working in the box, you may not hear the difference. But if you’re on a large-format analog console, such as an SSL or a Neve, and you compare a plug-in LA-2A to a real one, I think there’s no comparison. You’ll clearly hear the difference. It depends on your method of working. And that’s the point for all these things: Converters and clocks, for instance: I have converters and a clock that I love and that work well, and I know other people who say they love other ones. But they may be working in the box and not bringing things in and out much, or on a nice Neve console which is adding to the sound. It all depends on your situation, but as to outboard gear I don’t think there’s any question that the actual stuff still sounds a little better.

I see that you use an Apogee Big Ben external clock. Is that because you’re using a digital mixer, or would you use one anyway?

Well, I think that one sounds good, so I use that to clock everything. I use the Avid HD I/Os converters, clocked to the Big Ben. When they’re not clocked to that, they don’t sound as good to me. But when they are, they sound great.

Do you think it’s true in general that having a nice external clock, can make a big difference in the conversion?

It depends on your setup. Again, if you’re strictly in the box, I don’t know if you’re going to hear it. But if you’re using a lot of analog inserts, and clock different gear together, such as the console with the converters, then I think you will hear the difference. It also becomes a matter of taste.

Do you put effects on the master bus when you’re mixing? If so, which ones?

It varies. I never was one who did that a lot. I’ve never been one to squash the stereo bus. It just never works for me; I hear it too much. I compress it some, but it varies completely. For the past couple of years I’ve used the Vertigo VSC-2, which is a solid-state compressor. I like it a lot, it has a low-end rolloff for the sidechain, and you can also adjust the attack and release. It’s not cheap, but it sounds great. I’ll either use a little bit of that on the master, or, sometimes the API 2500 stereo bus compressor. That’s got a bunch of tone options on it. I don’t know what they call them: New, Vintage, Thrust, Loud, Medium, that kind of thing, which I find quite handy.

Do you hold back on the amount of master bus compression to leave room for the mastering engineer?

Yes, because they’ll always do more. There were times I used to print with and without it, but I’ve kind of given that up, because it’s just too many options. [Laughs] I get it as close as I can and then they’ll take it further. Digital tools are different. I have messed around with the digital plug-ins on the 2-bus at times, and if you want something really quick, they can work. I don’t have any favorites for that., though I’ve used the API plug-in when the analog unit wasn’t available.

You mentioned that you do everything at 96kHz. That’s one of those controversial subjects. Some people say 96 is pointless, and you might as well be at 48. Why do you do that?

Well, I came from the analog world. To me it was Neve and Studer. Neve consoles, Studer tape machines. And I feel like with everything I’m trying to do, I’m trying to get that sound. That’s what’s in my memory, that’s what’s in my head, in my feelings of everything. When digital first came out, it did not sound good to me. But when it went to 96kHz, and especially when it went to 24-bit, I felt that was the first time it sounded ok. I remember doing a session around 2000, for which we tracked to analog and then dumped it into Pro Tools at 24/96, and I thought, “This finally sounds good.” I felt I heard a slight difference in the bass, but everything else was great, and off we went. I did compare it with 48kHz and 44.1kHz, and to me, 96kHz is better. Again, it depends on your material. At least for acoustic, natural music. By acoustic I mean not synthesizers. It can be electric guitars. For real organic instruments, I think you can hear the difference.

In what, the high end? The transients?

It’s just a feeling of openness. It’s probably related to frequency response, a little, but I don’t think it’s that exactly. Now I also think a bigger thing that people miss is recording 24-bit. There’s a argument where people say “16-bit has way more dynamic range than you’ll ever need.” And I’ll say, on a final master modern record, that’s probably true. But when you’re tracking things, you don’t print everything at the hottest level it can be. So, even when recording at 24 bit you have a lot of things that are probably only getting recorded at 16 or 18 bit.

Do you have to pay a lot of attention to gain staging at 24/96, or is that less of an issue?

Yes, it’s a big issue. It comes down to your mic pre’s level and the fader level. So, you do have to pay attention to it. I try to get things hot, but reasonable. The beauty of it is that if things are on the hotter side, you can pull down your faders in your digital workstation. You couldn’t do that on a digital tape machine. So that’s a big convenience. Otherwise, what I suggest is that you put your console (playback) faders at 0 and get proper levels into the recorder.

You have to err on the side of not going over, right? If you have a very dynamic part, you should set your record levels lower to make sure it doesn’t go over?

Yeah. Because regardless of what people say, things do distort. They do go over. You’ll see the waveform flatten out. So, you do have room. That’s where the 24-bit comes in, because you can lower the level and still have a dynamic recording.

Thanks for your time, Dave.

You’re welcome!