This week we'll look into a side effect of compression that's beneficial, as long as you use it wisely. It's the so-called "glue" effect that takes place when you use a compressor on a group of tracks or even on the entire mix.

Why?

It’s pretty simple: If you use an adequately set compressor on a group of tracks, you can, to a certain extent, get a sensation of sonic cohesion. After investing a great deal of time and energy in painstakingly getting a clear and precise distinction between the different elements of your sonic puzzle, it might seem weird to want to go after such an effect. However, if you think about it, it’s a necessary stage. Especially these days, considering that most current productions are recorded track by track, mixing tracks that have been recorded with close-miking techniques in different locations with samples and/or virtual instruments. That’s why you need some overall cohesion, to make the listener believe that all the different elements form a single unit.

There are several ways to glue it all together, especially with reverb, as you will see later on. But before we get there, I’ll show you how a compressor can help you make your sonic puzzle more coherent.

How?

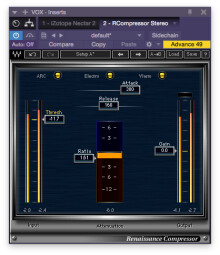

The best way to get the glue effect on several tracks is to send them all to a group track on which you should insert a compressor with the following settings:

- A very low ratio, somewhere between 1.5:1 to 2:1, tops, since you’re goal here is not to actually compress the signal

- A long attack time, to avoid deteriorating the peaks

- The release time ought to follow the groove, so the compressor breathes naturally, following the rhythm of the music. Do note that if your compressor features an automatic release-time function, it can work wonders in these situations!

- A relatively soft knee setting, so the compressor acts progressively, but not too much, otherwise the compression will be audible

- As for the threshold, lower it in a way that you get a maximum of –2dB of gain reduction, which is quite a lot, actually. Personally, I dial it in somewhere between –0.5dB and –1dB to get a more delicate result that goes unnoticed to the ear… until you take the compressor out of the mix.

One last remark before moving on. I think this trick works way better when you use compressors with character. By this I mean compressors that add some harmonic distortion, like a vintage analog compressor or a serious virtual emulation of one. Actually, in small amounts, this harmonic distortion acts as a sort of nice layer of varnish, making it easier to obtain the result you are looking for here.

When?

The glue effect is often used on drums, but also on a group of rhythm guitars, or a group of vocals, etc. In short, it can be very useful on groups of instruments of the same family, but not only. For example ─ even though I’ve never tried it myself, I know quite a few engineers who like to systematically group drums and bass and make them stick closer together.

As for using this trick on the entire mix, there are two clear and opposite schools of thought. There are those who won’t even start a mix without first having placed a stereo compressor on the master bus. And then there are those who argue that that’s the best way to tie the hands of the mastering engineer.

Before you ask, I belong to the first category, but that’s only me. I know lot’s of colleagues, whose work I deeply respect, who have another opinion on this matter. So, the best advice I can give you in this regard is to try both options for yourself and see what works best for you.