In this week's chapter, we'll tackle a specific use of compression you have surely heard about before, not least in our series of articles dedicated to mastering. I'm talking about parallel compression, which is sometimes called New York or NY compression. A highly valued technique among sound engineers, especially for drum tracks, but not only, as you are about to see...

Principles

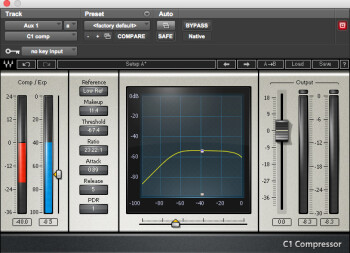

The concept behind this technique is relatively simple: Rather than inserting a compressor into the track you’re processing, you send the signal to an aux bus on which you’ve placed a compressor with really extreme settings. It’s not uncommon to use the following settings: Ratio as high as possible, ultra-fast attack to avoid even the slightest thing resembling a transient, a very, very fast release to create a pumping effect, the steepest knee available, and the threshold set as low as it gets. With such settings, the sound would obviously be awful: It pumps and distorts all the time; in short, it’s unusable.

However, if you bring down the fader of that aux bus and then you bring it up little by little to mix this overcompressed sound with the original sound, the result should bring a smile to your face! In fact, it will allow you to provide the processed signal with a solid foundation while, at the same time, giving it a lot of punch without deteriorating its peaks, preserving its lively character. If the compressor you use is a serious digital version of a vintage analog model, you should get a nice “old school” sound.

What for?

As I mentioned in the intro, parallel compression is often used on drums. And for obvious reasons: It allows you to make the sound bigger without taking away its natural dynamics. But it would be a pity to limit this trick to drums only. Applied to vocals, this technique can help bring weak syllables forward, making words more intelligible. On a bass guitar, it can help you gain some sustain without sacrificing the bassist’s groove. On “high-gain” guitars, it can reinforce the sensation of power. In short, it can be useful on any kind of instrument. However, as usual, be careful not to use it too much. Using parallel compression on every single track will not lead to a better sounding mix.

Before I finish, just a couple of remarks. First, there are some compressors that feature a knob to balance the source signal (dry) and the processed signal (wet). While it might be more practical, considering you only need to insert it into the track you want to process and then simply play with the knob in question, and without the need of an aux bus, personally, I still prefer the method described above. In fact, using an aux bus offers lots of other fine-tuning possibilities. You could, for example, EQ the overcompressed signal or send it to a reverb independent of the original source, etc. Not to mention the fact that many people tend to overdose on the dry/wet mix when it can be done directly on the compressor.

On the other hand, you should also know that, unfortunately, some plug-ins and DAWs don’t allow you to use the aux bus technique correctly, due to a latency compensation problem that causes major phase issues. If you ever sense some sort of “vagueness” when mixing the original signal with that of the aux bus, this could be the reason. If that’s the case, you will have to make do with a plug-in that features the dry/wet option.