Bob Ludwig, Doug Sax, Bernie Grundman - they're masters of mastering. They produce hit after hit, with nothing at their disposal other than...well, experience, talent, great ears, the right gear, and superb acoustics.

So maybe you’re missing one or more of those elements, and wish that what came out of your studio sounded as good as what comes out of theirs. So, why not just analyze the spectral response curves of well-mastered recordings, and apply those responses to you own tunes?

Why not, indeed – but can you really steal someone’s distinctive spectral balance and get that magic sound?

The answer is no…and yes. No, because it’s highly unlikely that EQ decisions made for one piece of music are going to work with another. So even if you do steal the response, it’s not necessarily going to have the same effect. But the other answer is yes, because curve-stealing processors can really help you understand the way songs are mixed and mastered, and point the way toward improving the quality of your own tunes.

As to the tools that do this sort of thing, we’ll look at Steinberg’s FreeFilter (which was discontinued, but still appears in stores sometimes), Voxengo CurveEQ, and Har-Bal Harmonic Balancer. They’re very similar, yet also, very different.

How They Work

FreeFilter and Voxengo split the spectrum into multiple frequency bands in order to analyze a signal. These create a spectral response, as from a spectrum analyzer, while a song plays back. During playback, the program builds a curve that shows the average amount of energy at various frequencies. You can apply this analysis (reference) curve to a target file so that the target will have the same spectral response as the analyzed file, as well as edit and save the reference file.

Har-Bal isn’t curve-stealing software per se. While optionally observing the response of a reference signal, you can open another file, and see its curve superimposed upon the reference. You can edit the opened file’s curve so it matches the reference signal more closely, but this is a manual, not automatic, process.

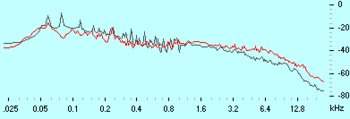

Fig. 1: The black line is the spectral response for Madonna’s Ray of Light; the red line represents a Fatboy Slim mix. Fatboy’s has a lot more treble, while Ray of Light has a serious low-end peak.

The manual vs. automatic aspect is in some ways a workflow issue. FreeFilter and Voxengo start by creating the reference curve, but give you the tools to adjust this manually because you’ll probably want to make some changes. Har-Bal takes the reverse route: You start out manually, and if you want to, use the tools to create something that resembles the visual reference curve, which was generated automatically when you opened the file. Also remember that curve-stealing is only a part of these programs’ talents; they’re really sophisticated EQs.

So what do some typical curves look like? Check out Fig. 1. The black line is the spectral response for Madonna’s “Ray of Light, ” while the red line represents a Fatboy Slim mix. Past about 1 kHz, Fatboy’s curve shows enough high frequency energy to shatter glass. “Ray of Light” has a higher response below about 400 Hz, due mostly to a prominent kick. It has a more thud-heavy, disco kind of vibe, whereas Fatboy Slim leans more toward a techno style of mastering. Apply these curves to your own music, and they’ll take on the characteristics of the reference tunes – but the results may not be what you expect, as we’ll see.

The Software

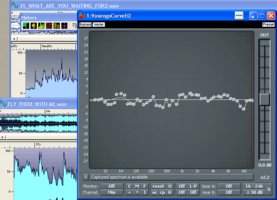

Fig. 2: Steinberg’s FreeFilter was an early curve-stealing/EQ program. Its sound quality is lacking by today’s standards, but its functionality set the paradigm for this type of software.

The software needs to analyze two files: the reference and the target. It compares the two, and raises or lowers the target curve’s response to match that of the reference.

Fig. 2 shows the spectral response graph for Steinberg’s FreeFilter; it illustrates what happens after applying the source’s curve to the destination. The green line displays the target curve, while the red line shows the result of applying the reference. The yellow line shows the response correction curve generated by FreeFilter to match the two curves. The 30 sliders are like those on a graphic EQ; they modify the curve represented by the yellow line.

It’s crucial to be able to change the degree to which the reference influences the target. With FreeFilter’s morph control at 0%, you hear the original destination sound. At 100%, the two curves match. You can even go past 100%, which exaggerates any changes. Generally, it seems settings in the 20% – 50% range almost always gives better results than 100%, because then the source curveinfluences, rather than dominates, the destination.

With Voxengo CurveEQ, you can again see the filter’s frequency response, input spectrum, and output spectrum. It also includes goodies not found in other programs: The “GearMatch” feature includes impulse responses of pieces of classic gear you can apply to a tune. Additional limiting, saturation, and voicing can further color a piece of music.

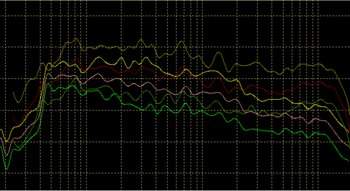

Fig. 3: Voxengo’s CurveEQ has analyzed the song in the rear window, matched it to the current song in the front window, and generated a compensating response curve so that the current song’s spectrum matches the reference. This curve can be tweaked further.

When you want to capture and apply a curve, you can load a reference file, or play a file (in real time) into CurveEQ and capture its response. You then load the target file you want to process, and match the two. CurveEQ generates a filter response that matches the current file to the reference (Fig. 3), which you can then tweak by dragging on the small handles.

With its vintage gear and dynamics processing options, CurveEQ is intended to be more of a complete mastering solution than FreeFilter or Har-Bal. Of course, if you’re not careful you can overdo things, but a hint of saturation of vintage compression can indeed add some sparkle. And as it’s a plug-in, CurveEQ can work with individual tracks as well as program material, although you need to be careful about delay compensation.

Har-Bal has several interesting aspects. First, it’s stand-alone, not a plug-in, and runs under ASIO, WDM, or MME.

Ill. 4 : Har-Bal

The interface is extremely easy to use and responsive in terms of drawing curves; you can adjust peaks, average, and a mean of the two separately (Fig. 4). For example, you would bring down excessive peaks on the peak line, and bring up “holes” in the average line. Har-Bal also has a volume compensation feature so that the equalized and bypassed sounds have the same apparent volume. This allows you to base your judgments solely on what EQ contributes to the overall sound, rather than being influenced by level differences. Another talent is the ability to match average levels among tunes.

Because CurveEQ and Har-Bal seem superficially similar, they’re often lumped together as similar programs. But actually, they do things in very different ways, and have very different workflows and optimizations. For pure EQ curve adjustments to fix problems, Har-Bal gets the nod. But that’s all it does. CurveEQ does a lot more, including automatic curve-stealing with the ability to “morph” curves like FreeFilter, but is not as versatile in terms of having separate control over peak and average amounts. Frankly, you kind of need to have both if you want all the features, but fortunately, both have downloadable trial versions so you can determine for yourself which one satisfies your particular needs better.

Sounds Good, What’s the Catch?

For EQ adjustments, these are extremely useful programs. But if you’re into stealing curves, be forewarned – there’s a fundamental flaw in the concept. For example, I grabbed an audio reference from a Spice Girls CD (yes, I’m not ashamed to admit it, so sue me) because it had a nice, overheated kind of pop mastering approach and I want curious how it would affect some of my cuts. There’s a serious treble boost on the girl’s voices to make them airy; it sounds great with the Queens of Auto-Tune, but when applied to one of my tracks, the treble boost made the overdriven guitar screechy. However, reducing the influence of the reference tamed the treble boost, trimmed the bass, and did produce a more pop-sounding curve.

Then there are times when curve-stealing doesn’t really make a difference. I had a dance tune and thought hey, “Ray of Light” was a big dance hit, let’s see what happens when I apply it to my tune. So I did, and…nothing. Then I realized why: I had mastered my tune with virtually the same spectral response.

So does that mean I had mastered my tune as well as the big-bucks experts who did “Ray of Light”? Well, no – my tune needed a bit more high end. So a curve can point you in the right direction, but don’t count on it to complete the job.

So What Does Work?

Using your ears to compare your work to a well-mastered recording is a tried-and-true technique, but it shortens the learning process when you can actually compare curves visually and see what frequencies exhibit the greatest differences.

I’ve found a few reference comparison curves for Har-Bal that work well for certain types of music: Fatboy Slim for when dance mixes are too dull, “Ray of Light” for a house music-type low-end boost, Cirque de Soleil’s “Alegria” for rock music, and Gloria Estefan’s “Mi Tierra” for acoustic projects. On very rare occasions I use their curves, but when I do, they’re more like “presets” because they end up getting tweaked a lot. Automatic curve-stealing just doesn’t do it for me, but “save me 10 minutes by putting me in the ballpark” does.

But my main use for curve-analyzing software is for stealing from myself. After mastering a music project for a soundtrack, one tune sounded a little better than the others – everything fell together just right. So, as an experiment, I subtly applied its response to some of the other tunes. The entire collection ended up sounding more consistent, but the differences between tunes remained intact – just as I’d hoped.

Another good use was when German musician Dr. Walker remixed one of my tunes for a compilation CD, but used a loop for which he couldn’t get legal clearance. Rather than give up, I created a similar loop that wasn’t a copy, but had a similar “vibe.” Yet it didn’t really do the job – until I applied the illegal loop’s response curve to my copy. Bingo! The timbral match was actually more important than the particular notes I played in terms of making the loop work with the rest of the tune.

This does produce a weird paradox, though: I used a piece of curve-stealing software to avoid stealing a piece of copyrighted material. I guess it’s all part of the living in the 21st century.

Originally published on Harmony Central. Reprinted with permission.