In the last article, we saw how chords have a natural tendency towards other chords depending on their degree in the key of the song where they are currently been employed.

Throughout this series I have introduced you to different cadences, especially the perfect cadence. For more on that, I invite you to reread article 7.

In the next couple of articles I’ll try to diverge a bit from the somewhat (or maybe too?) theoretical subject at hand and introduce you to a number of progressions that are among the most widely used in Western music, both classical and modern. I won’t be going into too many details, though, I’ll touch on any necessary explanations later on. Thees articles will give us the opportunity to plunge into more practical matters. So I invite you to try these progressions on your favorite instrument and I’m sure you’ll quickly realize how familiar some of them sound!

A brief reminder

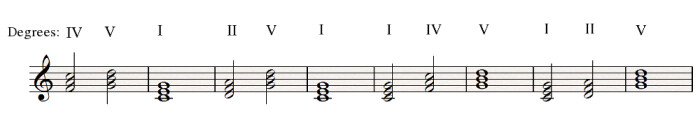

First of all, remember that a perfect cadence, the famous V-I, is usually introduced by the preceding chord, namely the IV degree. The latter has a subdominant function, just like the II degree of the scale, which can be used to replace it. This results in the following cadences:

- IV-V-I

- II-V-I

- I-IV-V

- I-II-V

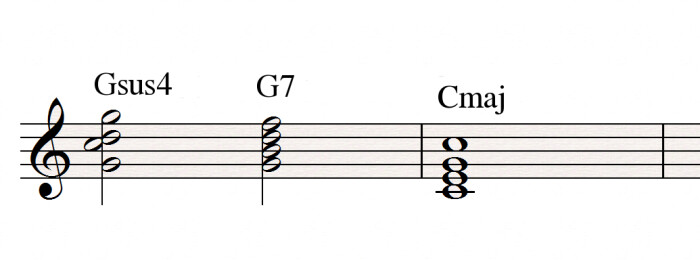

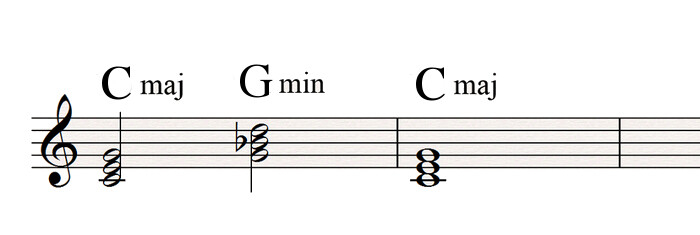

You can also use the Vsus4 before the V degree. In a "sus4" chord, you replace the third of the chord with a perfect fourth, which results in the following chord:

Picardy and Andalusian cadences

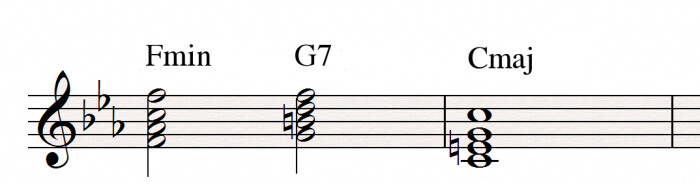

Two cadences that we haven’t seen yet are the Picardy and the Andalusian cadences. Some people say Picardy refers to the French province of the same name, while some others say it has more to do with the Old French term “picart, ” which would translate as “sharp.” Anyway, whatever the meaning and origin, this cadence is easily distinguishable from all the other cadences we’ve seen so far, which stick solely to one mode, be it minor or major. However, with the Picardy cadence, a song in minor mode ends with a major chord.

The idea behind this is to make the song end in a positive note or to give it a sense of glory. This technique was very often used by Johann Sebastian Bach.

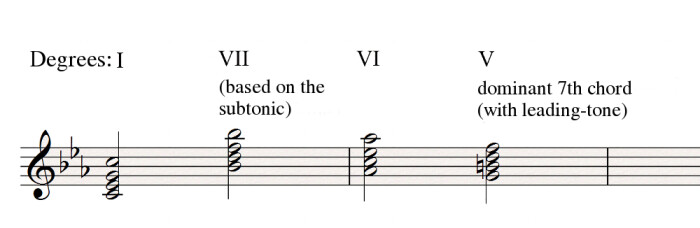

The “Andalusian” cadence, which gets its name due to its wide use in flamenco music, looks like this

I min – VII maj (7th degree of the natural minor scale, based not on the leading-tonebut rather on the subtonic) – VI maj – V7:

Besides Spanish music, this formula can also be heard on “Don’t Let Me Be Misunderstood” or Ray Charles’ “Hit the Road, Jack.” This is an example of a minor cadence, which we’ve spoken very little about until now.

Borrowing from the minor mode

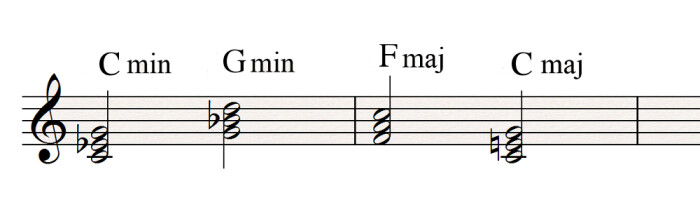

Other cadences, although not properly minor, do not hesitate to borrow some elements from minor modes. So, in the following formulas, the V degree is directly taken from the minor mode:

I-Vmin

or

Imin-Vmin-IV-I

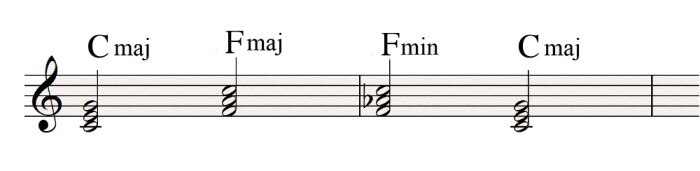

A cadence that is very frequently used is the one that makes use of the minor 4th degree, like this: I-IV-IVmin-I. Like I said in the opening of the article, try them out and you’ll see…sorry, you’ll hear, that they sound quite familiar.

In the next article we’ll see how certain cadences can be linked to each other, as well as the “star” cadences used in popular music.