In the previous articles we looked at how cadences work and how the fifth degree of a scale tends towards the first degree (yes, I know I've been repeating this every article). But, regardless of cadence, chords show a natural tendency to lead to other chords. If you know the different attractions between chords, you can easily and quickly build a naturally coherent harmonization.

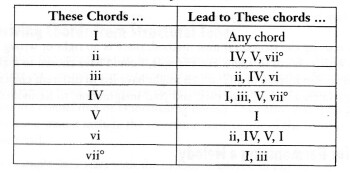

As we saw in article 9, every key has stable and unstable chords. Stable chords don’t require any special resolution, since they can resolve to several chords. On the other hand, unstable chords often need a specific resolution, like in the example of the perfect cadence where the V degree calls for a resolution to the 1st degree. This is called “chord-leading.” In the table below you can see which chords lead to which other chords:

It’s also important to point out that not every chord leading has the same impact. You could classify them according to their decreasing impact as follows:

- ascending perfect fourth, descending perfect fifth

- descending perfect fourth, ascending perfect fifth

- ascending second

- descending third

- descending second

- ascending third

This is what makes the VI-II-V-I progression we saw in article 7 so powerful, since it’s made up exclusively of strong leading movements between chords: descending perfect fifth and ascending perfect fourth (the latter often transformed into a descending perfect fifth).

In an upcoming article we’ll see how the first degree of the scale isn’t the only that benefits from being reinforced by the dominant. And in yet another installment we’ll see what is it that makes chords attract.

However, to finish this episode we could look into the so-called leading-tone.

Follow the leader

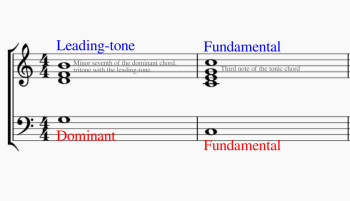

It’s important to note that the leading-tone, in other words the seventh degree of a major, harmonic minor or melodic minor scale, has a strong tendency to resolve to the tonic juts a half step above it (the seventh degree of a natural minor scale, located one whole step beneath the tonic, is not considered a leading-tone, it’s called the sub-tonic).

And, as if by chance, it’s easy to realize now that the dominant chord includes the fifth degree, which leads towards the lower tonic and the seventh degree, which leads toward the upper tonic. So there’s a double tendency towards the tonic!

To finish, it’s easy to observe that when you use a seventh dominant chord, the minor seventh added to the triad (a three-note chord) based on the dominant results in a tritone (see article 9) with the second note of the chord and an attraction towards the third note of the tonic chord.