Throughout the relatively short lifetime of PA systems, both manufacturers and users have thought about ways to evaluate the performance of a system as objectively as possible.

A series of parameters, grouped under the term “specifications, ” provides useful information regarding this stage in the audio chain. For users, understanding these specifications reduces subjectivity when evaluating a speaker system, even if the final judgment will never be 100 percent objective (just as not everybody has the same musical taste).

On the manufacturers side, there is no obligation to provide serious information about the products they sell, athough they generally do when their products are aimed at knowledgeable amateurs or professionals. But when it comes to consumer electronics, the specs are less detailed and the values often seem to be pulled out of a hat. That’s why we think this basic introduction to the main technical specifications you can find on a speaker’s spec sheet is important.

Defining frequency response

The frequency response represents the frequency range a speaker can produce optimally in terms of tonal balance — in other words, the frequencies whose amplitude differences are not significant in relation to the source. At the very minimum, it should state the limits of this frequency range (the cutoff frequencies in Hertz), together with a figure quantifying the maximum divergence between the input and output signals (in dB SPL, which stands for Sound Pressure Level). Without this tolerance value, the specified frequency response doesn’t really make much sense. Unfortunately, displaying frequency responses that go very down low boost sales, which explains why manufacturer’s often find it tempting to forget to specify the amplitude differences between input and output.

A correctly specified frequency response, like 60 Hz – 20 kHz (+/- 3 dB) means that the speaker can produce a signal going from 60 to 20,000 Hertz with a tolerance of 3dB, depending on the frequency. Measuring conditions have been the subject of a lot of discussions. Anechoic chambers aren’t exactly the same and have a hard time absorbing lows. Open-field measurements (without any reflecting surfaces, except for the ground) vary depending on the height of the speaker. And the position of the measurement mic is also controversial. If the speaker has two drivers, you have to make sure that the microphone is at the same distance from both. The distance to the mic may vary depending on how many ways the speaker has.

Behind the numbers

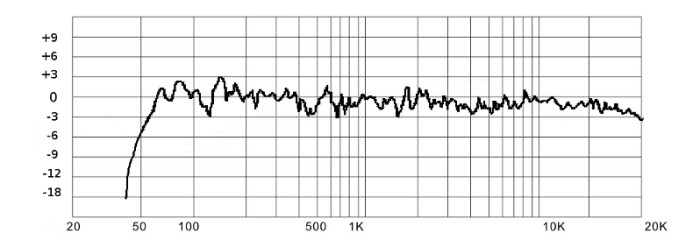

A +/- 3dB variation can correspond to both a very uneven or a very flat frequency curve. The result can sound very different even if the response shows the same values. To be able to understand the differences, you’ll need to look at the curve representation, with the frequencies on the horizontal and the amplitude on the vertical axis. But even if the curves are very similar, two speakers designed differently will sound disparate, since the variations in level with regard to the (perfect) flat response might have different causes.

|

Frequency response example

|

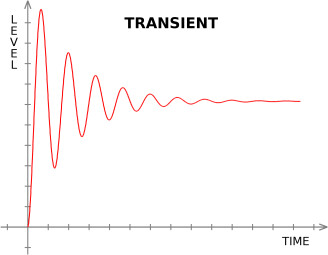

A bump or dip might be caused by a resonance of one of the speaker components or a reflection of the signal on the surface of the speaker cabinet, which will have dissimilar effects on how it ultimately sounds. Looking at the frequency curve, you have no idea of how the speaker behaves in time. And what about transients, those very brief moments when the amplitude varies very rapidly? Maybe some frequencies have a tendency to lag behind…which you can’t tell from the frequency response.

A word on phase response

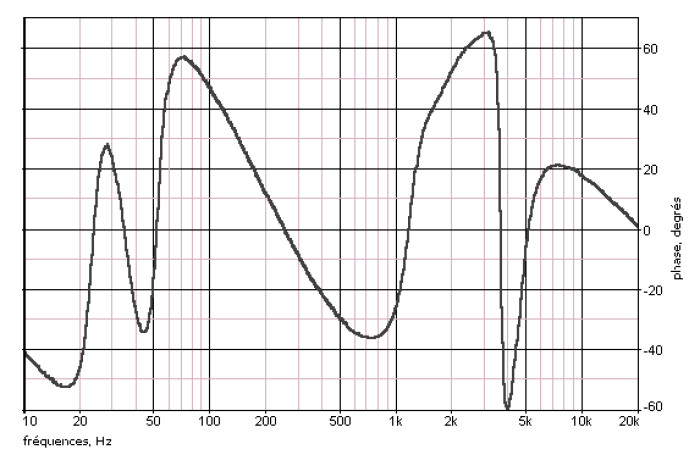

While frequency response indicates amplitude distortions, phase response indicates time distortions. Phase response is much harder to measure and interpret. And it’s hardly ever published in catalogs. It’s measured in degrees, like an angle. If a signal has a phase variation, it is considered as a time delay applied to the signal. If this delay isn’t the same for all frequencies within the specified frequency range, the phase response curve will be altered. In the best-case scenario, it ought to be flat, and there shouldn’t be any dependencies between phase and frequency.

|

Phase response example

|

The difficulty involved in having a speaker reproduce all frequencies with the exact same latency might entail signal degradation, which can prove problematic, especially for sounds with short attack times. Since not all frequencies that make up a sound are time-aligned with the source, it affects the reproduction of transients. A piano note or a pizzicato, for instance, would lose precision in the attack, which in turn makes the speaker sound unnatural.