This is the next installment in our article series dedicated to the race for volume, its consequences on music, sound and human ears.

The previous articles in this series were intended to make you realize that the main reason behind the race for loudness is of commercial, rather than artistic nature. But let’s not neglect the other main reason for this race, which has to do with the current understanding of what mastering is, contrary to its original meaning: The proliferation of digital audio has made it possible for anybody to produce music at home with a stunning quality. It’s even easier when you create everything “in the box, ” in other words, without recording anything and using exclusively sounds coming from the computer itself (sample libraries, synths, etc.).

Don’t get me wrong, I’m not whining about it. The possibilities that digital audio technology offers are huge, and have allowed musicians to escape from the toxic record label system and its practices, which have little to do with artistic creativity (does anybody even remember what “talent scouting” means?) and are mainly focused on making a profit.

Mix or mastering?

While the decline of the influence of the major labels has widened the playing field considerably, it has also significantly reduced the number of albums being produced in professionally designed and treated studios. Instead, many independent releases are recorded in DIY spaces like bedrooms, garages or basements, which have little or no acoustic treatment. Granted, some people do manage to produce great music in non-treated spaces, but they are the exceptions to the rule.

More often than not, home-based mixes will feature many defects due to the characteristics of the room, the lack of practice and know-how and the gear used (no matter how good your monitor speakers are, they will never be able to replace an acoustically treated room equipped with a pair of Westlakes, for instance). It’s perplexing, to say the least, to see people mix in a 100 sq. ft. room using huge speakers (for the size of the room) placed on a desk, almost glued to the wall and with a subwoofer…

One of the most common mistakes is bass management, since most monitors don’t go low enough to adequately reproduce the lower frequencies, not to mention the (phase) problems that a non-treated room exhibits. All this results in people overloading the mix with lows. And since low frequencies require lots of energy to be heard, a vicious circle begins: You increase the lows and compress it, since it hits the 0dB mark right away. Then you bring up the rest to make it stand out a bit. As a consequence, the mix lacks lows again, so you increase and compress them a bit more, and so on.

And, in my opinion, that’s where the logic starts to fail: Conscious that their productions won’t ever sound like commercial ones (although that depends on what you use as a reference), musicians turn to mastering engineers to fix the problem (by the way, as far as I know, there’s no formal training to become a mastering “engineer” nor an officially recognized diploma that credits such mastery). If the mix isn’t good, the most reasonable thing to do would be to take it to someone to fix it, right? Namely, to a mixing engineer, not a mastering one.

Nobody is spared

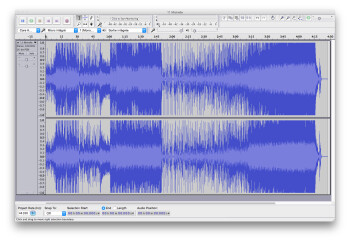

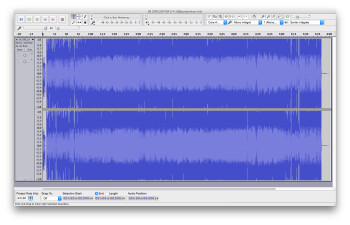

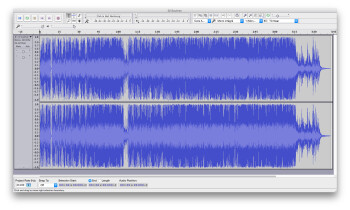

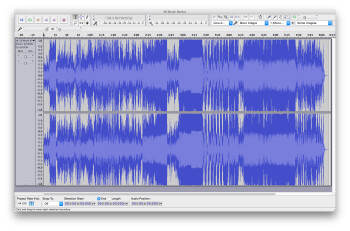

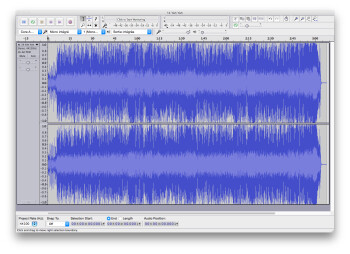

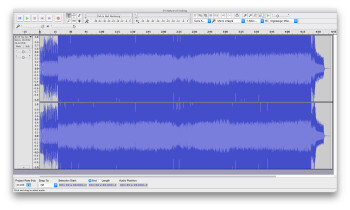

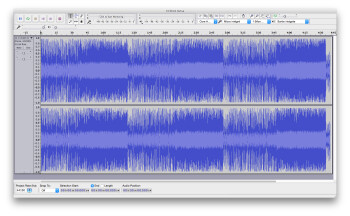

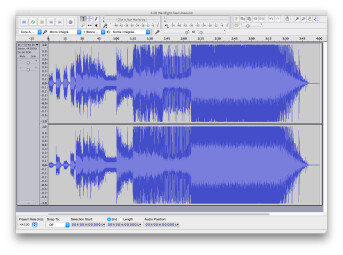

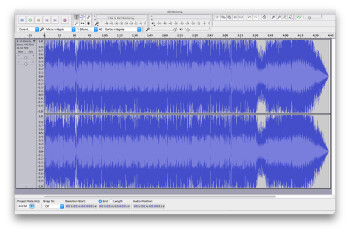

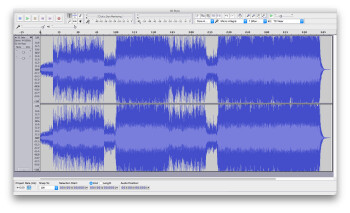

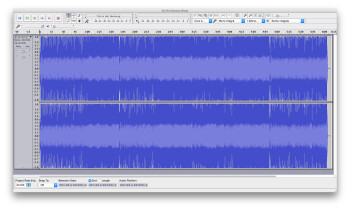

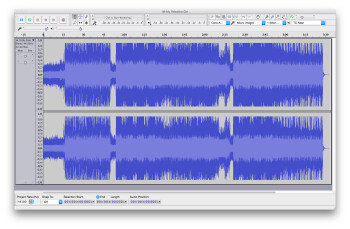

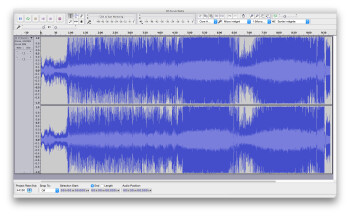

Over-compression of music is not a phenomenon limited to home-recorded albums, however, it’s everywhere. Below you have a series of screenshots of more or less recent tracks, from jazz to pop, rock, EDM, fusion, etc., which will illustrate the problem.

The only genre missing is classical (and contemporary) music, which remains relatively oblivious to this trend, even though it has its own issues, like recording a work bit by bit, section by section, instead of recording it all in one go (the number of mics used on an orchestra can be overwhelming sometimes, with all the problems it entails…). But that’s by no means a recent practice, as you can read in Jonathan Cott’s “Dinner with Lenny: The Last Long Interview with Leonard Bernstein.”

Enough said. Here’s the list.

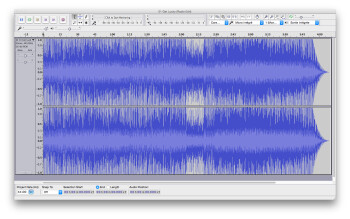

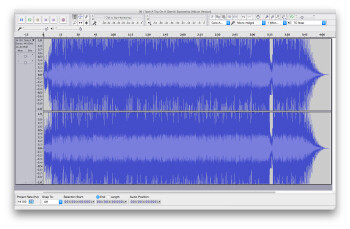

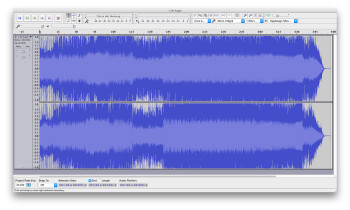

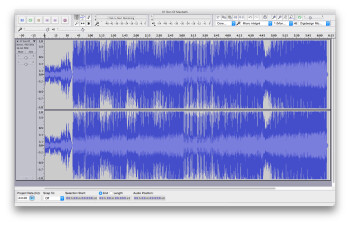

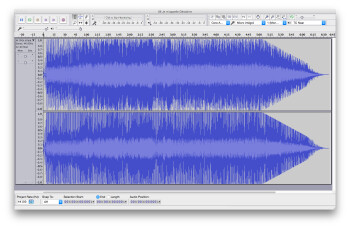

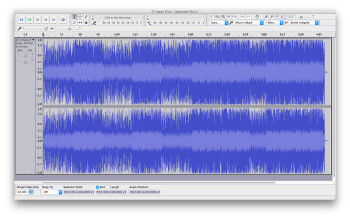

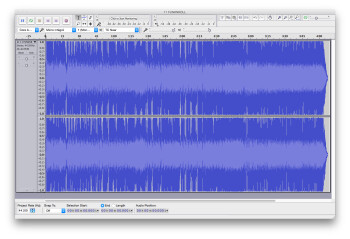

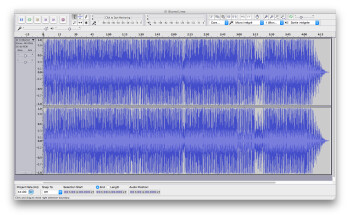

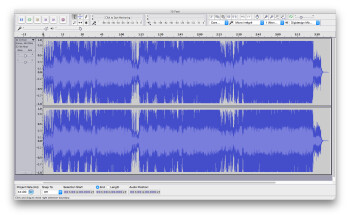

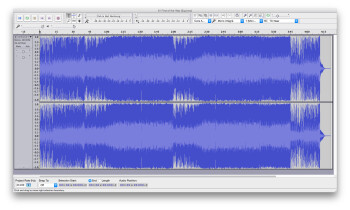

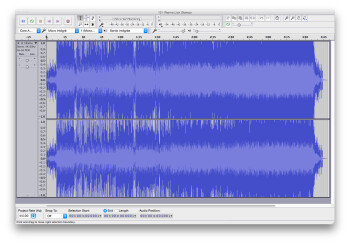

We’ll begin with Antiloops, and their song “Michelle, ” from the Electroshock album (2015). Dynamic range: 6dB.

Aphex Twin, “Circlont6a, ” from the Syro album (2014). Dynamic range: 3dB.

Ben L’Oncle Soul, “Soul Man, ” from the Ben L’Oncle Soul album (2010). Dynamic range: 7dB.

Björk, “Mouth Mantra, ” from the Vulnicura album (2015). Dynamic range: 4dB.

Daft Punk, “Get Lucky, ” from the Random Access Memory album (2013). Dynamic range: 8dB.

David Bowie, “I Took A Trip On A Gemini Spaceship, ” from the Heathen album (2002). Dynamic range: 6dB, intersampled clipping.

Depeche Mode, “Angel, ” from the Delta Machine album (2013). Dynamic range: 4dB.

Diana Krall, “Yeh Yeh”, from the Wallflower album (2015). Dynamic range: 7dB, intersampled clipping.

Iamx, “Nature Of Inviting, ” from the Kingdom Of Welcome Addiction album (2013). Dynamic range: 4dB.

Ibrahim Maalouf & Oxmo Puccino, “Simili Tortue, ” from the Au Pays D’Alice… album (2014). Dynamic range: 9dB.

James Blake, “We Might Feel Unsound, ” from the James Blake album (2011). Dynamic range: 3dB.

Kendrick Lamar, “Momma, ” from the To Pimp A Butterfly album (2015). Dynamic range: 5dB.

Marcus Miller, “Son Of MacBeth, ” from the Afrodeezia album (2015). Dynamic range: 7dB.

Orchestre National De Jazz, “Je M’Appelle Géraldine, ” from the The Party album (2014). Dynamic range: 8dB.

Pharell Williams, “Happy, ” from the Despicable Me 2 album (2014). Dynamic range: 8dB.

Prince, “Funkroll, ” from the Art Official Age album (2014). Dynamic range: 5dB, intersampled clipping.

Robin Thicke, “Blurred Lines, ” from the Blurred Lines album (2014). Dynamic range: 9dB, intersampled clipping.

Selah Sue, “Feel, ” from the Reason album (2015). Dynamic range: 4dB.

Skrillex, “First Of The Year (Equinox), ” from the More Monster And Sprites album (2011). Dynamic range: 5dB.

SLuG, “I Wanna Lick Stamps, ” from the Namekuji album (2012). Dynamic range: 5dB, intersampled clipping.

Taylor Swift, “Style, ” from the 1989 album (2014). Dynamic range: 5dB.

Toto, “21 st Century Blues, ” from the Toto XIV album (2015). Dynamic range: 6dB.

Tricky, “My Palestine Girl, ” from the Adrian Thaws album (2014). Dynamic range: 5dB.

Trilok Gurtu & Simon Phillips, “Kuruk Setra, ” from the 21 Spices album (2011). Dynamic range: 7dB, intersampled clipping.

Help!

Before I finish, let me remind you that the maximum sound pressure level of personal music players is regulated by law in many countries. Listening to a personal music player at high volumes can lead to hearing damage (temporary or permanent hearing loss, ear buzzing, tinnitus, hyperacusis). So it is recommended not to use a player at high levels for more than an hour everyday.

Regardless of the player/telephone you use (and without considering that if you jailbreak into a phone you can make it go up to 130db!), listening to any of the albums listed above in its entirety at high volumes would probably result in an irreversible degradation of your hearing capabilities. Why? Well, because all of them have what you could call a constant level, considering their lack of dynamics. This means that if you listen to them at loud levels, you would be exposed to a very high sound pressure level all the time (for instance, if the listening level is 100dB and the album has a dynamic range of 4dB, the overall constant level is 96dB. Now take another look at the table with the maximum sound exposure times).

It has nothing to do with music genres, trends or any other aesthetic considerations. It’s a public health problem. Your health.

You’ve been warned.