Though there are other conventions, it is generally agreed that the kick drum goes into the first channel of the console, and for time immemorial, inordinate efforts have gone into tediously adjusting it.

| http://a3.twimg.com/profile_images/313810739/psw_twitter_reasonably_small.jpg Article is provided by ProSoundWeb |

Sound check never really starts until after this first input has been tweaked to satisfaction.

The kick drum is the cornerstone of rock. It puts the pop in pop music and is the one input that holds it all together. It’s the heartbeat of rock and roll.

With most input channels, the goal is to accurately recreate the original sound, but with kick drum an ideal is constructed from the available material.

Perhaps it’s in channel one because it defines ‘one.’

First Things First

If you want good sounding drums, the drums must first sound good. Though it sounds like a platitude, sound checks frequently grind to a halt while someone looks for a drum key. Crap drums always provide crap sound (garbage in, garbage out), but the same kit, properly tuned, sounds completely different.

You don’t have to be a drummer to know how to tune drums, though it helps. However, plenty of drum techs are living proof that anyone can learn.

When foldback speakers began battling it out with Marshall stacks and Sunn Coliseums, taking the front head off the kick drum became a necessity to provide a degree of isolation and allow the mic to capture the attack of the beater hitting the head.

The use of a pillow to dampen the head began, no doubt by a sleepy drum tech, and as years went by, the art of the hole in the front head evolved.

There are three ways of setting up a kick drum: with heads on both sides, batter head only, or with a hole in the front head. The latter compromise has become the rule, as it provides access for mic placement, while retaining some benefits of the resonant head, and over time the hole has gotten smaller and moved away from the center.

Countless back-lounge discussions have been logged on this topic. It’s generally agreed that anything larger than 6 inches (a roll of duct tape) releases too much air and performs like no head at all (other than to keep the pillow inside), and a hole in the center also releases too much pressure.

Cutting a hole with a utility knife can have disastrous results and is a job for the skilled or experienced. Heating a coffee can on a stove and pressing it into the head can melt a hole that’s even and smooth.

And in case you were wondering, the 4-o’clock position for an offset hole became traditional because a boom arm reaching across the head causes the weight of the mic to tighten the screw on the mic clip and keep the mic in position.

Batter head tension should be no more than a half-tum past taking the wrinkles out. The front head’s tension affects the batter head, and should be slightly looser for the fullest sound.

Over-dampening kills tone. Felt strips cause more trouble than good, as they keep the head from correctly tensioning.

It’s often best to only lightly dampen the heads, to control decay, and Drum Workshop makes an hourglass-shaped pillow that’s held in place with Velcro to lightly touch both heads.

Before you even turn on the kick mic, do everyone a favor and listen up close. If it doesn’t sound good acoustically, there’s little that will make it sound great in the PA, short of replacing it with a sample. (Surely the next digital mixing console trick is a built-in Wendell Jr. that plays back the drum from last night’s show or the drum from the record.)

Now HIT the drum. The kick drum seems simple to play, but can seem mediocre during a line check with a tech or stagehand’s foot at work, yet suddenly sounds great when the actual drummer shows up, as long as he plays it the way he will during the show.

Properly playing a kick drum takes a well-toned leg, built up from years of bouncing the heel.

Maybe playing back a sample of a previous show’s kick is a good idea until a real drummer arrives.

Time is frequently wasted turning knobs, when a twist of the mic stand’s boom arm is what’s really needed. While the engineer is wrestling with the first input, it’s helpful to have an interested tech assist at the kit, by listening up close and standing by to adjust the drum pillow, mic angle, or simply offering suggestions about how it sounds.

Let’s look at our mic options.

Legends

Kick drum mic choices have evolved over the years. In the beginning there were few alternatives and no ‘kick drum’ mics. There were just vocal mics and instrument mics.

Eventually a few models emerged as favorites: the venerable Sennheiser MD421, the solid EV RE20 and the exotic but fragile AKG D 12E.

The fallback was simply a Shure SM57, and at a pinch an SM58 worked equally well, as they’re nearly identical. The old gaffe about the sound company with both kinds of mics: 58s and 57s was true back in the day, with the first exception being a special kick drum mic, where it does really matter.

The road-dog trick in the 1970s was to modify a 57 by taking the transformer out and connecting the capsule directly to the XLR, a ploy rediscovered by budget recording enthusiasts.

This modification drops the gain by 10 dB—perfect for kick drum applications—while also removing the cheap transformer that saturates upon extreme SPL.

You’ll want to mark this mic so as not to confuse it, unless you end up modding all your 57s.

Old roadies can confirm that the Sennheiser 421 was first choice for years, and still is for many. I bought my first a quarter-century ago, and when I replaced it with a new one, I sold the dented old one for more than I paid for it.

Long ago they were used for vocals, so it was important to check the roll-off ring. A secret weapon is its cousin, the 441. With its tighter pattern, it rejects more stage wash and can be more easily focused onto or away from the click of the beater.

EQ’ing the kick drum is a skill with millions of man-hours invested, yet the simple truths are that mids must be cut, while lows and highs are boosted.

General-purpose mics need a wide cut around 400 Hz.

Indeed, in the 1980s, one reason 4-band fully parametric EQs were demanded for premium live consoles was that the secret to kick drum EQ was the celebrated “double-midrange-cut, ” with boosts at 80 Hz and 2 kHz.

A single midrange cut employs a wider bandwidth that steals thump and click at its skirts. Few inputs needed four bands as badly as the kick, and this helped drive the sales of premium live consoles.

Desks with swept mids, but fixed highs and lows, force one filter to be tuned as a low-mid cut, and the other to bring out the click, or to ‘put a point on it, ’ in the vernacular.

Classics

By the 1980s other mics contended for the first channel.

The beyerdynamic M 88, originally introduced as a premium hypercardioid dynamic for a wide variety of applications, was eventually discovered to be an outstanding kick drum mic.

However, repeated exposure deteriorates the compliance of the membrane and imparts a “wooly” sound that some actually prefer for the drum, but is no longer acceptable when combined with proximity effect on vocals.

Informed users therefore clearly mark their M 88s as to their designation for drums or vocals.

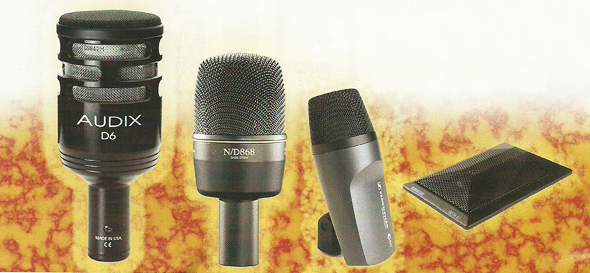

|

and the newer RE320, which includes a switchable curve designed for kick drums. |

The Electro-Voice RE20, heralded for bringing out the fullness of radio announcers, was also discovered to bring depth to the kick drum.

This mic was followed up a few years ago with the RE27 N/D which employs a neodymium-alloy magnet, hotter output, extended HF, a presence peak at 4 kHz, and provides two low-cut filters instead of one, plus a high-cut.

The AKG D 112 became the first “application specific” kick-drum mic, partly in response to complaints about expensive D 12E studio mics breaking down under high SPL in the kick drum. Today it remains one the most popular, and the first to marry aesthetics to functional contoured frequency response. It looks cool and sounds great.

The Audio Technica ATM25 followed as a great hypercardioid utility mic, and it has been compared to a highly directional rugged D 12E.

For more news and information for the audio professional visit ProSoundWeb.