When amplifying an acoustic guitar, the use of a microphone can lead to concerns about feedback as well as being able to adequately amplify the instrument. With electric guitars, there are also concerns about the microphone adequately and accurately picking up the sound from the guitar amp, and in many cases, there’s also a desire for a quieter stage.

| http://a3.twimg.com/profile_images/313810739/psw_twitter_reasonably_small.jpg Article is provided by ProSoundWeb |

Both scenarios lead to the use of direct (or DI) boxes as an alternative. But note that when selecting a direct box, the choice is very different when dealing with acoustic versus electric guitars.

The Acoustic Take

Most acoustic guitars are either equipped with a built-in piezo pickup with an on-board active preamp, or they can be outfitted with an after-market magnetic pickup that fits inside the sound hole.

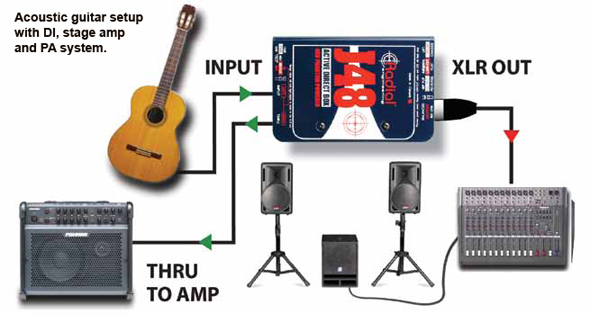

The high-impedance output from the instrument is then sent to a direct box where the signal is balanced and the impedance is lowered to enable it to be sent a long distance without noise.

A typical direct box is equipped with a “thru” connector that is used to feed the artist’s stage amp, while the balance low-impedance XLR output feeds the sound system.

The traditional approach to using a direct box is to capture the signal right from the instrument before it is processed on stage by the musician. The thru output going to the stage amp allows the artist to adjust the EQ or add echo to suit his personal needs on stage.

At the same time, this setup enables the front of house engineer to add reverb or coloration to suit the room without having to try to compensate for the effects added by the musician.

As noted, eliminating feedback on stage is a primary concern. Some DI boxes are equipped with a built-in high-pass filter that can reduce unwanted low-frequency resonance that often leads to feedback. This also reduces the energy content, resulting in greater headroom. More headroom means less distortion – another common cause of feedback.

Reversing the polarity at the DI output can also be very helpful as this changes the phase relationship between the sound coming from the system and the sound coming from monitoring system on stage. By electronically “moving” the acoustic peak so that it becomes a valley, hotspots that can cause resonant feedback can be eliminated.

Best of all, because these fixes do not involve using EQ to fight feedback, the instrument’s tone is not negatively impacted.

The Electric Take

Particularly since the advent of in-ear monitors, guitarists have become much more aware of the sound from their amps.

Before IEM, when they played guitar on stage, they were listing to their amps.

Today, they hear what the mic is picking up, and more often than not, they’re realizing that the sound doesn’t match up real well when compared with what they hear coming from their amp.

This makes sense. When a mic is placed right in front of a loudspeaker, a tremendous amount of effort is required by the sound engineer to make it sound “good/right.” Move the mic just a centimeter and the sound can change.

Further, as you go to different venues, the sound once again is subject to change do to a variety of variables. This includes different room acoustics, proximity and bleed from other instruments, the effect of stage resonance, and of course, mic placement.

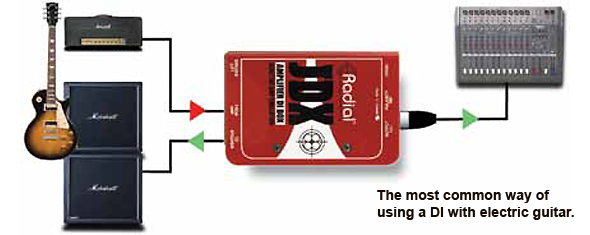

However, using a traditional direct box in front of the amp does not work. The guitar sound needs to be captured after it has been processed by the amp.

And as any sound engineer can attest, simply placing a regular direct box with a pad at the output tends to sound like a swarm of bees. The requirement is to replicate the sound of both the amp and the cabinet.

Recent advances have allowed engineers to develop new direct boxes that employ advanced filtering to better replicate the sound. And by employing the loudspeaker as a reactive load, the sound coming from the direct box tends to be much more realistic.

The benefits to using a guitar amp direct box – correctly – can be significant. For the artist that is using in-ear monitors, the audio engineer can program the mixer and effects for tremendous consistency night after night. This means sound checks can be done quicker.

And when the artist is comfortable and happy, it generally results a better performance. For the sound engineer, the starting point is immediately familiar, which eliminates “fighting” the mix for the first several songs.

The quality of a mix starts with the sources, and delivering a better mix improves the show for the audience.

For more news and information for the audio professional visit ProSoundWeb.