The critics are right: pitch correction can suck all the life out of vocals. I proved this to myself accidentally when working on some background vocals.

I wanted them to have an angelic, “perfect” quality; as the voices were already very close to proper pitch anyway, I thought just a tiny bit of manual pitch correction would give the desired effect. (Well, that and a little reverb.)

I was totally wrong, because the pitch correction took away what made the vocals interesting. It was an epic fail as a sonic experiment, but a valuable lesson because it caused me to start analyzing vocals to see what makes them interesting, and what pitch correction takes away.

And that’s when I found out that the critics are also totally wrong, because pitch correction—if applied selectively—can enhance vocals tremendously, without anyone ever suspecting the sound had been corrected. There’s no robotic quality, it doesn’t steal the vocalist’s soul, and pitch correction can sometimes even add the kind of imperfections that make a vocal sound more “alive.”

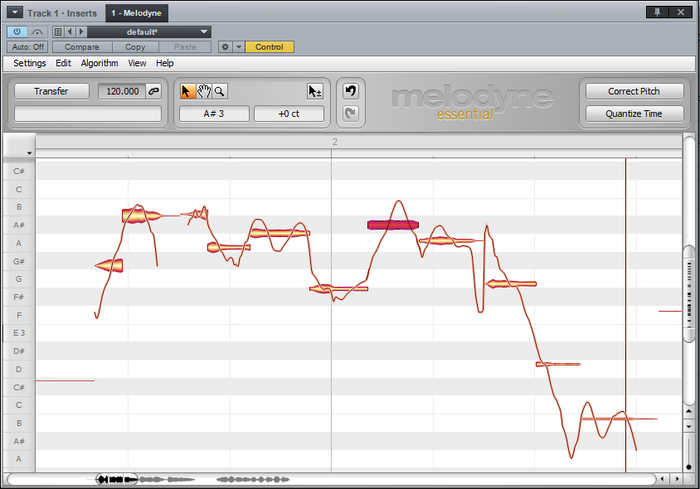

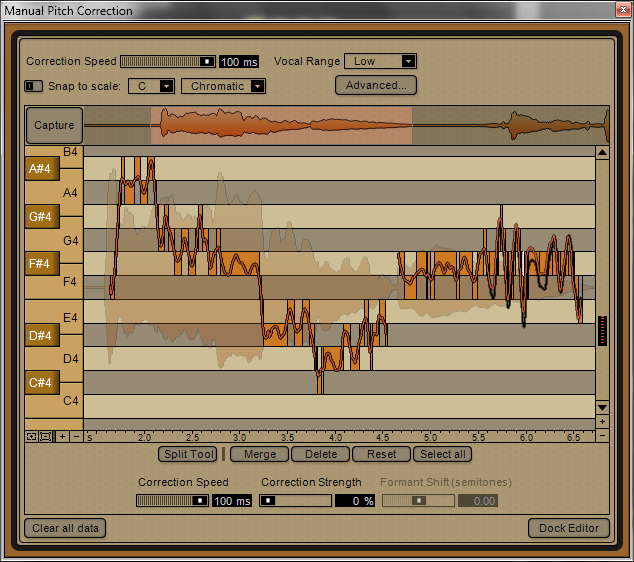

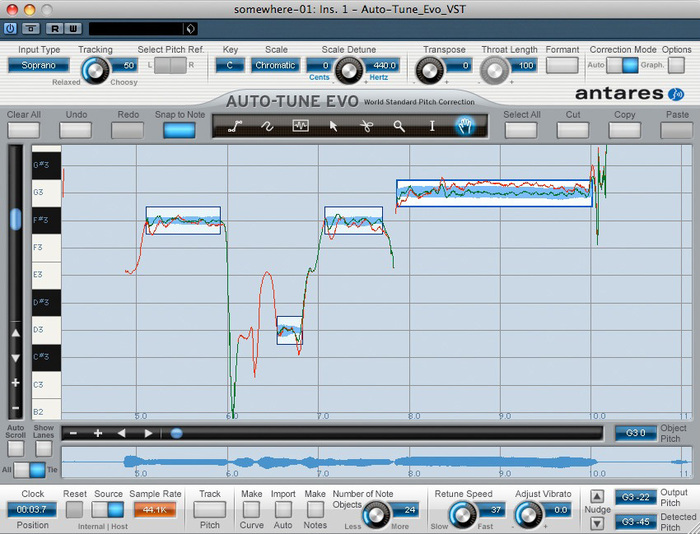

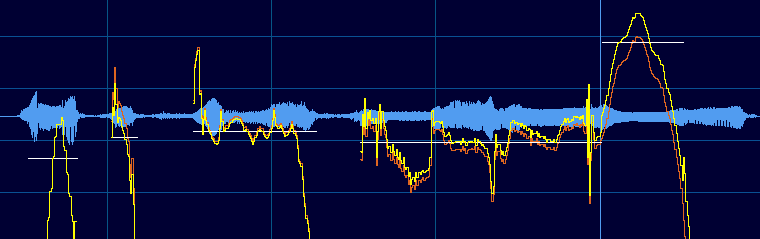

This article uses Cakewalk Sonar’s V-Vocal as a representative example of pitch correction software, but other programs like Melodyne (Fig. 1), Waves Tune (Fig. 2), Nektar (Fig. 3), and of course the grand-daddy of them all, Antares Auto-Tune (Fig. 4), all work fairly similarly. They need to analyze the vocal file, after which they indicate the pitches of the notes. These can all be quantized to a particular scale with “looser” or “tighter” correction, and often you can correct timing and formant as well as pitch. But more importantly, with most pitch correction software you can turn off automatic quantizing to a particular scale, and correct pitch with a scalpel instead of a machete. That’s the technique we’re going to describe here.

Fig. 1: Celemony Melodyne

Fig. 2: Waves Tune LT

Fig. 3: iZotope Nectar's pitch correction module

Fig. 4: Antares Auto-Tune EVO

Beware Signal Processing!

Pitch correction works best on vocals that are “raw, ” without any processing; effects like modulation, delay, or reverb can make pitch correction at best glitchy and at worst, impossible. Even EQ, if it emphasizes the high frequencies, can create unpitched sibilants that confuse pitch correction algorithms. The only processing you should use on vocals prior to employing pitch correction is de-essing, as that can actually improve the ability of pitch correction to do its work.

If your pitch correction processor inserts as a plug-in (e.g., iZotope’s Nektar), then make sure it’s before any other processors in the signal chain.

What to Avoid

The key to proper pitch correction use is knowing what to avoid, and the prime directive is don’tever use any of the automatic correction options—unless you specifically want that hard correction, hip-hop vocal effect (in V-Vocal, these are the controls grouped under the “Pitch Correction” or “Formant Control” boxes). Do only manual correction, and then, only if something actually sounds wrong. Avoid any “labor-saving” devices; don’t use options that add LFO vibrato. In V-Vocal, I always use the pencil tool to change or add vibrato. Manual correction takes more effort to get the right sound (and you’ll become best friends with your program’s Undo button), but the human voice simply does not work the way pitch correction software works when it’s on auto-pilot. By making all your changes manually, you can ensure that pitch correction works with the vocal instead of against it.

Do No Harm

One of my synth programming “tricks” on choir and voice patches is to add short, subtle upward or downward pitch shifts at the beginning of phrases. Singers rarely go from no sound to perfectly-pitched sound, and the shifts add a major degree of realism to patches. Sometimes I’ll even put the pitch envelope attack time or envelope amount on a controller so I can play these changes in real time. Pitch correction has a natural tendency to remove or reduce these spikes, which is partially responsible for pitch-corrected vocals sounding “not right.” So, it’s crucial not to correct anything that doesn’t need correcting.

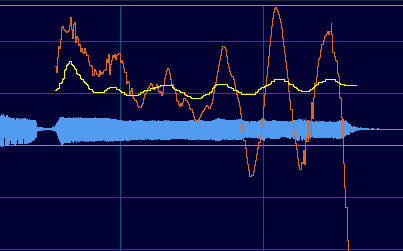

Consider the “spikey” screen shot (Fig. 5), bearing in mind that the orange line shows the original pitch, and the yellow line shows how the pitch was corrected.

Fig. 5: The pitch spikes at the beginning of the notes add character, as do the slight pitch differences compared to the “correct” pitch.

Each note attack goes sharp very briefly before settling down to pitch, and “correcting” these removed any urgency the vocal had. Also, all notes except the last one should have been the same pitch. However, the first note being slightly flat, with the next one on pitch (it had originally been slightly sharp), and the next one slightly sharp, added a degree of tension as the pitch increased. This is a subtle difference, but you definitely notice a loss if the difference is “flattened” to the same pitch.

In the last section the pitch center was a little flat; raising it up to pitch let the string of notes resolve to something approximating the correct pitch, but note that all the pitch variations were left in and only the pitch center was changed. The final note’s an interesting case: It was supposed to be a full tone above the other notes, but the orange line shows it just barely reached pitch. Raising the entire note, and letting the peak hit slightly sharp, gave the correct sense of pitch while the slight “overshoot” added just the right amount of tension.

Vibrato

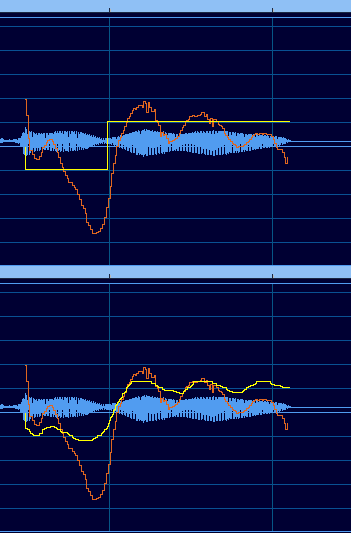

Another problem is where the vibrato “runs away” from the pitch, and the variations become excessive. Fig. 6 shows a perfect example of this, where the final held note was at the end of a long phrase, and I was starting to run out of breath. Referring to the orange line, I came in sharp, settled into a moderate but uneven vibrato, but then the vibrato got out of control at the end.

Fig. 6: Re-drawing vibrato retains the voice’s human qualities, but compensates for problems.

Bearing in mind the comments on pitch spikes, note that I attenuated the initial spike a bit but did not flatten it to pitch. Next came re-drawing the vibrato curve for more consistency. It’s important to follow the excursions of the original vibrato for the most natural sound. For example, if the original vibrato went up too high in pitch, then the redrawn version should track it, and also go up in pitch—just not as much. As soon as you go in the opposite direction, the correction has to work harder, and the sound becomes unnatural. This emphasizes the need to use pitch correction to repair, not replace, troublesome sections.

Also note that at the end, the original pitch went way flat as I ran out of breath. In the corrected version, the vibrato goes subtly sharp as the note sustains—this adds energy as you build to the next phrase. Again, you don’t hear it as “sharp, ” but you sense the psycho-acoustic effect.

Major Fixes

Sometimes a vocal can be perfect except for one or two notes that are really off, and you’re loathe to punch. V-Vocal can do drastic fixes, but you’ll need to “humanize” them for best results.

In the before-and-after screen shot (Fig. 7), the pitch dropped like a rock at the end of the first note, then overshot the pitch for the second note, and finally the vibrato fell flat (literally). The yellow line in the top image shows what typical hard pitch correction would do—flatten out both notes to pitch. On playback, this indeed exhibited the “robot” vibe, although at least the pitches were now correct.

Fig. 7: The top image shows a hard-corrected vocal, while the lower image shows it after being “humanized.”

The lower image shows how manual re-drawing made it impossible to tell the notes had been pitch-corrected. First, never have a 90 degree pitch transition; voices just don’t do that. Rounding off transitions prevents the “warbling” hard correction sound. Also note that again, the pitch was re-drawn to track the original pitch changes, but less drastically. Be aware that often, the “wrong” singing is instinctively right for the song, and restoring some of the “wrongness” will enhance the song’s overall vibe.

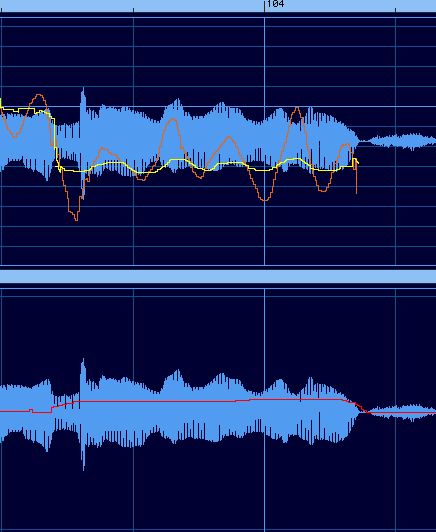

Shifting pitch will also change the formant, with greater shifts leading to greater formant changes. However, even small changes may sound wrong with respect to timbre. Like many pitch correction program, V-Vocal also lets you edit the formant (i.e., the voice’s characteristic timbre). When you click on V-Vocal’s F button, you can adjust formant as easily as pitch (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8: The formant frequency has been raised somewhat to compensate for the downward timbre shift caused by fixing the pitch.

In the screen shot with formant editing, the upper image shows that the vibrato was not only excessive, but its pitch center was higher than the pitch-corrected version. The lower pitch didn’t exactly give a “Darth Vader” timbre, but didn’t sound right in comparison to the rest of the vocal. The lower image shows how the formant frequency was raised slightly. This offset the lower formant caused by pitch correction, and the vocal’s timbre ended up being consistent with the rest of the part.

A Real World Example

To hear these kind of pitch correction techniques—or more accurately, to hear a song using the pitch correction techniques where you can’t hear that there’s pitch correction—check out the following music video. This is a cover version of forumite Mark Longworth’s “Black Market Daydreams” (a/k/a MarkydeSad and before that, Saul T. Nads), and there’s quite a bit of touch-up on my vocals. But listen, and I think you’ll agree that pitch correction doesn’t have to sound like pitch correction.

Originally published on Harmony Central. Reprinted with Permission.